The Machine-Human and the Myth of Superintelligence

We live in an age where AI is celebrated as humanity’s next great leap – the path to artificial general intelligence (AGI), superintelligence and a society that automates everything. But behind the hype lies another story: our creativity is bodily, born of crises and lived experiences, and cannot be programmed. At the same time, we risk becoming increasingly machine-like ourselves, as technology shapes how we see the world and ourselves. The most radical innovation of the future is therefore not a supercomputer – but a human being who refuses to become a machine.

Artificial intelligence dominates today’s technological discourse. Many predict that machines will soon match or surpass our own intelligence, which would render human intelligence obsolete. Billions have been poured into this dream, and the brightest minds are given time and resources to open Pandora’s box.

Proponents of this view, such as Nick Bostrom, argue that because intelligence rests on physical substrates – like the human brain – there is no reason it could not be recreated on a much larger scale, unbound by the confines of the human skull (Bostrom, 2014).

But is this really possible – or are we just building castles in the air?

The Theory of Cyclical Development Undermines the AI Hype

According to the theory of cyclical development – which I have previously presented on this blog – human intelligence and creativity go beyond algorithms. They are part of life itself, deeply rooted in existential experiences and crises, and they are non-deterministic.

Early Homo sapiens learned survival through imitation within a rhythmic song system that maintained extremely durable lifeways over hundreds of thousands of years. Mirror-neuron networks made it possible to accurately imitate toolmaking and movement patterns across generations. During evolution the brain did not grow because we became ever more creative; it grew because we became better at reproducing and consolidating survival strategies that already worked.

The original function of language was therefore, in the form of song and rhythm, to guide people in their daily tasks – to synchronise thought and body, individual and environment – rather than to constantly invent new things. The free, infinite language, the abstract speech we now take for granted, arose much later. Only about 75,000 years ago did the vocal song system shift to a fully symbolic language, unleashing not only new ways of thinking and communicating but also new ways of moving.

When sudden environmental changes made old routines impossible – for example ice-age pulses and above all the Toba super-eruption – the song system “overheated”. Song ran idle, cognitive dissonance arose, experimentation exploded and new tools, art forms and social systems were born.

Language was an invention of innovative people in a tumultuous time – and this applies to all our ancestors in the genus Homo who went through the same cyclical process. Even Homo erectus and Homo heidelbergensis experienced crises and invented new survival strategies, then let the brain and the song cement the new solutions and lifeways, whereupon the brain grew larger again.

This represents a Copernican revolution in how we view human evolution – we flip the coin: larger brains did not evolve to make us ever more ingenious, but to effectively reproduce acquired survival strategies and close the gap between body and thought, human and habitat – through song and mirror neurons. Creativity continued to develop but as a latent reserve beneath the solid surface – ready to break through when the next crisis tore down imitation’s hegemony.

This means that genuine creativity and innovation are deeply rooted in the human body: in emotions, sensory impressions and physical interaction with the world. They arise out of cognitive dissonance – the tension between expectation and experience, between body and soul – and they are not deterministic. They emerge from chaos and are truly free and transformative.

Machines, by contrast, lack frustration, wonder and joy. They manipulate symbols but have no conscious relationship to them.

Human intelligence thus did not emerge through a gradual, deterministic natural selection where generation after generation became ever smarter in response to a changing environment. It arose latently – and when it finally burst forth it was untamed and went beyond the programmable, as part of life’s very lifeblood. This cannot be recreated in a laboratory – no more than we can create life itself.

Large Language Models and Their Limitations

Our largest language models operate strictly within a logical, stripped-down system of propositions. There is hardly any genuine creativity there – only rapid, massive recombination of already existing texts. This stands in sharp contrast to how actual scientific and intellectual breakthroughs occur.

Alfred Russel Wallace had his evolutionary insight while feverish in Indonesia – the idea of natural selection struck like a revelation, not as the result of formal deduction. Albert Einstein described “the happiest thought of my life” when, working at the patent office in Bern, he imagined an observer in free fall – a sudden flash of insight that later led to the general theory of relativity and fundamentally changed our worldview.

Such non-logical breakthroughs lie completely beyond today’s LLM architecture. Today’s AI – even the most sophisticated models – engage in algorithmic manipulation of symbols without lifeblood. They lack the existential creativity that only appears when imitation’s chains break, when body and thought collide and free language arises. AGI presupposes a “brain in a box” that can evolve without a physical, existential embodiment. All of this AI lacks.

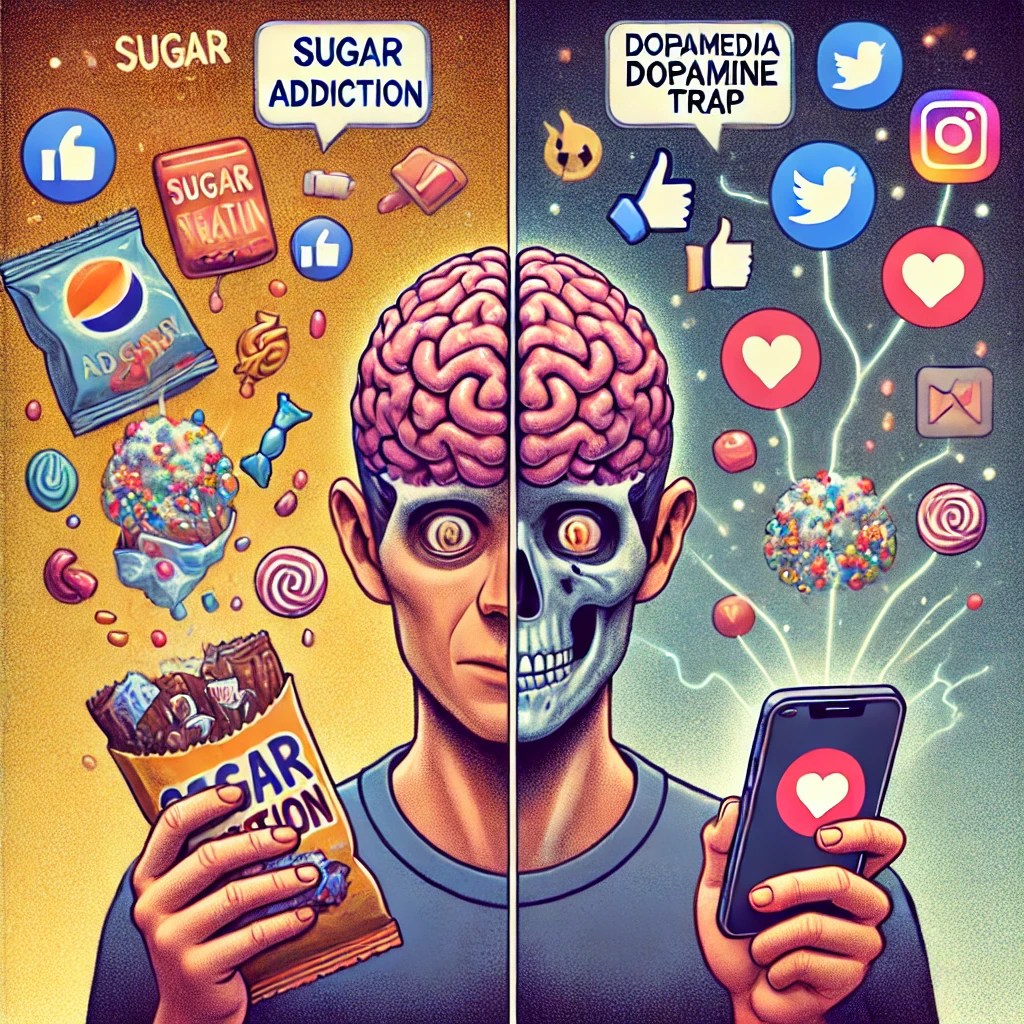

The Machine-Human – The Real Danger

Ironically, it is not technology that is becoming more human today, but humans who risk becoming more machine-like. Philosopher Martin Heidegger spoke of technology’s ability to “unconceal” reality – to make us see the world in a new way. In the new computerised era we are reduced to data points, patterns and functions that can be optimised. When the world is revealed through the grid of technology we begin to see ourselves as resources, as machinery.

This has two crucial consequences:

- Loss of human dignity. If humans are seen as just another algorithm, the foundation of our inviolability dissolves. People become interchangeable, measurable and comparable in the same logic as raw materials and means of production. We are seen as programmable automatons – a view that threatens to dehumanise us and in the long run erode human rights. If we start to see people as fallible machines rather than moral subjects, we open the door to a society where the value of each person can be measured, priced and – in the worst case – switched off.

- Humans become technology. In our drive for efficiency and optimisation we ourselves become increasingly machine-like. We live by measurable rules, let algorithms guide our decisions and make ourselves ever more bound by laws. It is not technology that becomes human – it is we who become technology.

Heidegger would say that this is the real danger: not technology itself, but that we see the world – and ourselves – only through the grid of technology. We then forget other ways of being human, other ways of living and understanding ourselves.

Heidegger’s allegory of everyday language and poetry offers a powerful tool for understanding this danger. He did not mean that poetry arose from everyday language as its highest form, but rather the opposite – that the original language was poetic, open and full of wonder. The first modern humans were thus grand poets (Heidegger, 1971). It is this poetry, this spiritual and non-physical dimension, that is now being lost in the AI era.

AI Is Like Any Other Technology

AI is fundamentally like any other technology. It is not exceptional; it cannot create by itself but only in interaction with humans – just like writing, the wheel and other groundbreaking innovations.

But the danger is that AI risks reinforcing an already ongoing, dehumanising process – a process that capital accumulation in symbiosis with technology has long driven. Technology shifts boundaries and stretches its tentacles deep into the periphery to suck resources into the centre, just as human ecologist Alf Hornborg has shown (Hornborg, 2022). In the centre, people become intoxicated by the illusion of freedom and dream of eternal life. But in practice we feed the machines – not the humans – something the gigantic, extremely energy-hungry data centres demonstrate with brutal clarity.

Reclaim the Human

Even though we will never achieve either artificial general intelligence or superintelligence – something that will likely soon burst the AI bubble with enormous economic consequences – AI will still become an ever larger part of the infrastructure that feeds injustice and alienation. Economic power will concentrate into even fewer hands, and at the same time we risk changing ourselves: becoming ever more standardised, ever more governed by the logic of algorithms, ever more entangled with technology – and ever less poetic.

The most radical innovation of the future is therefore not a supercomputer – but a human being who refuses to become a machine.

References

Bostrom, N. (2014). Superintelligence: Paths, Dangers, Strategies. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Heidegger, M. (1971). Poetry, Language, Thought. Trans. A. Hofstadter. New York: Harper & Row. (Includes the lecture “…dichterisch wohnet der Mensch…” delivered 1951.)

Hornborg, A. (2022). The Magic of Technology: The Machine as a Transformation of Slavery. London & New York: Routledge.

Staying with the Sama Bajau: Life, Change, and Resilience at Sea

During the trip to Indonesia we also visited Sulawesi and several Bajau communities. Already in Jakarta I met a Sama Bajau man named Yakub, author of Anak Atol (literally “a child of an atoll”), a book describing the childhood of a boy growing up on a small coral island—an experience shared by many Bajau. I asked him about the practice of intentionally rupturing the eardrums, and he explained that it is ”harus”—it is a must—for those who want to make a living from diving. It is truly an initiation rite!

Between Reef and Open Sea: Life and Fishing in Topa

After leaving Java, we travelled to the island of Buton in southeast Sulawesi, where we visited the Sama Bajau community of Topa in Kamaru—a place Erika had first visited back in 1988 during her earlier travels in Southeast Asia.

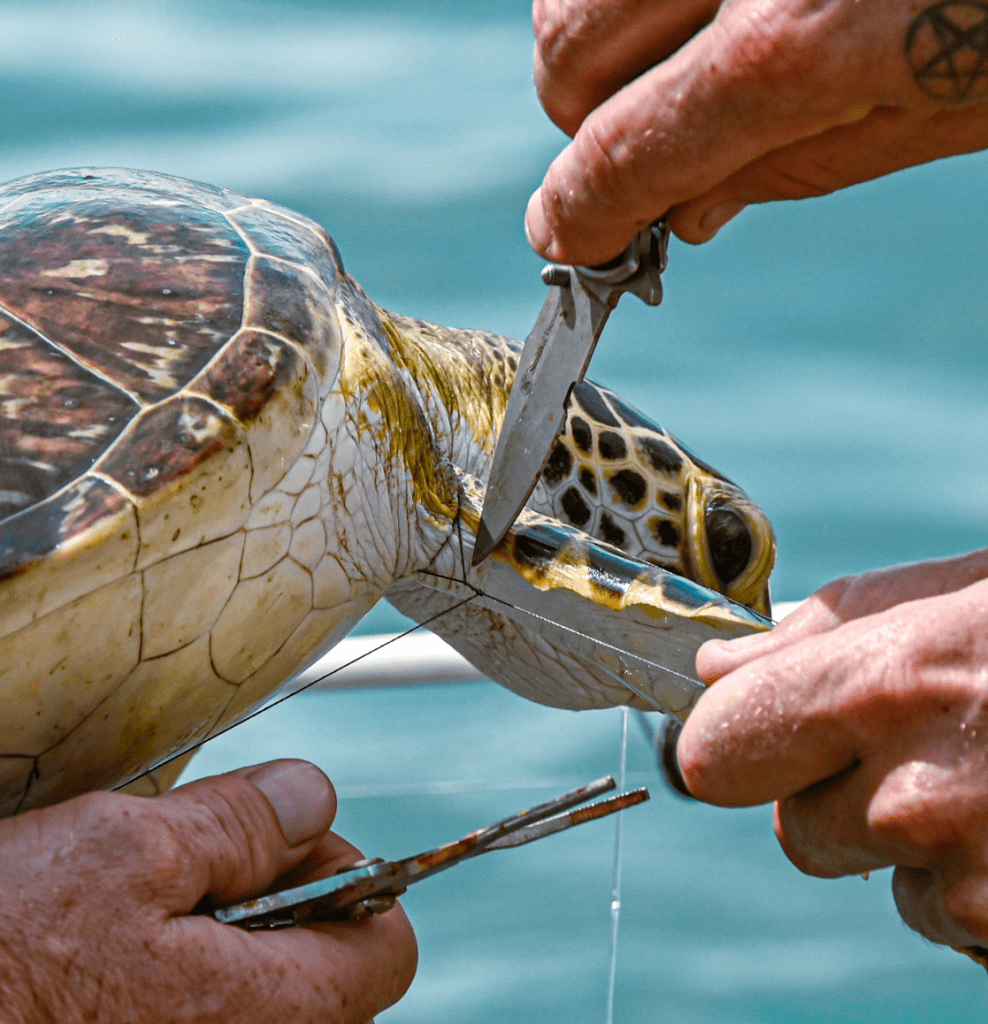

In Topa, we followed on local fishing trips. Fishing had not been good lately: fewer fish were being caught, and our usual speargun fishing trips were not very successful. While we were fishing, a nearby family group was using a compressor while searching the coral wall for large and lucrative fish. As a matter of fact, many skilled freedivers – as for example Si Mansor – have now shifted toward offshore tuna fishing, using hook and line far out at sea—a more lucrative livelihood than spearfishing coral reefs. They can travel for hours to reach tuna grounds and stay at sea for long periods. Some even remain on the boat for months during the right season.

Others remain closer to the community, choosing either high-investment fishing—using compressors to stay deeper for longer periods and target high-value fish—or very low-cost methods without motorized boats, where small but sufficient profits are made through skilled diving, such as catching mantis shrimp, which requires experience and precision but can generate good income.

These strategies are often mixed: intensive trips during certain seasons, combined with more traditional fishing close to home to meet household needs while staying in the village.

The fishermen of Topa voiced frustration over Sama Bajau from the Kendari region who enter the area with speedboats and use fish bombs, which has caused noticeable declines in reef fish. Despite this, during a visit to the nearby village of Lasalimu, we were greeted by dolphins—a beautiful reminder of what still persists.

We also visited the grave of Husimang, who had hosted Erika already in 1988. His wife—still alive—joined us, along with their children and grandchildren, as we climbed the hills together.

Clams, Recycling, and Creative Survival

During our visit to Lasalimu, we met a woman selling the meat of giant clams. One whole clam sold for only 25,000 rupiah—barely more than 1.5 USD—shockingly low for a species protected since 1985.

In the village, we met a group of children wearing traditional wooden goggles who had been collecting shellfish. They proudly showed us their catch and later followed us to the pier, happily throwing themselves into the water, diving and swimming with ease.

Back in Topa, we observed small but ingenious forms of recycling, such as chairs made from used motorcycle wheels. Our host was buying various shells, including abalone, to sell in bulk in Baubau, where they are used for jewelry or clothing buttons. People continually find creative solutions and new livelihoods in a world where fish are becoming increasingly scarce.

Across Borders: Mola, Australia, and the Politics of the Sea

After our stay in Topa, we travelled onward to Wangi-Wangi in Wakatobi National Park, staying close to Mola—with a population of around 8,000, probably the largest Sama Bajau community not only in Sulawesi but in Indonesia.

Here I met an old acquaintance, Saiful, a Sama Bajau man who had learned English during a year spent in an Australian prison for illegal fishing. One night, he picked me up in Wanci town on his motorcycle, and we rode together to Mola for coffee.

Saiful’s brother-in-law joined us—married to Saiful’s sister. He is Bugis, but now fully integrated into the Sama Bajau community; I could tell no difference.

“He is skilled in hook-and-line fishing,” Saiful said.

We spoke about Saiful’s experiences in Australia, which reminded me of a conversation I had had in Topa just a few days earlier with an elderly man who had travelled to Australia many times and had been arrested and sent to Bali. He told me that some younger Sama Bajau even hoped to be caught, believing Australia offered opportunity—though in reality, they would usually be sent to Bali because they were underage.

In the Riau Islands, the Bajau community of Pepela was founded by migrants from southeast Sulawesi, and strong social and kinship ties remain between Pepela and villages such as Mola and Mantigola. Shark fishing has become increasingly difficult, and many men no longer travel there, yet the networks connecting these communities remain strong.

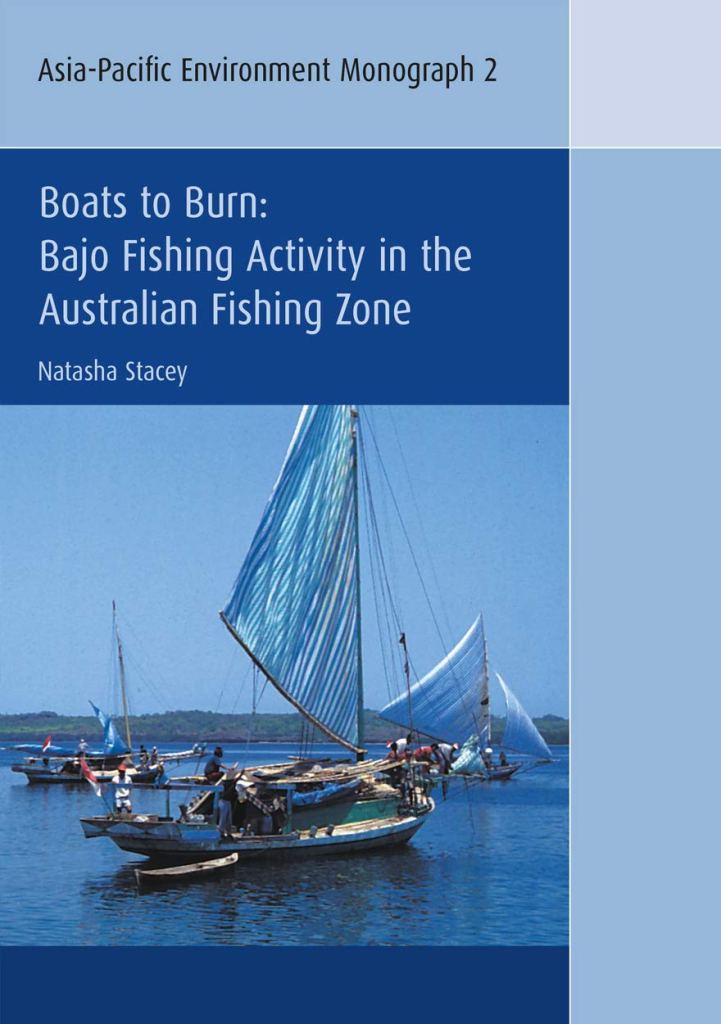

Anthropologist Natasha Stacey has written extensively about Sama Bajau fishing activities in Australian waters. In Boats to Burn, she describes how the construction of traditional perahu lambo sailing vessels persisted in southeast Sulawesi because Australian law, for a time, allowed only traditional boats—not motorized vessels—into its fishing zones.

This policy inadvertently preserved a boatbuilding tradition that had already disappeared in many other Indonesian Sama Bajau communities. It is a clear example of how global politics and national borders can shape—and sometimes sustain—local practices, technologies, and ways of life.

Life Along the Reef: From Sampela to Satellite Houses

A few days later, we arrived in Sampela, where we again stayed with Pondang, in the traditional stilt houses—now used as homestays—that we once helped construct. For two days, we joined local speargun fishermen on the surrounding coral reefs. Fishing was better than in Topa, but still far from what it used to be, despite Sampela’s proximity to an extensive reef system.

We also travelled to the outer reefs known as sapak, where some Sama Bajau have built temporary stilt houses—so-called satellite houses—for distant fishing. Here, fishing was noticeably better, with larger fish more common than near the main community. The area benefits from its location inside Wakatobi National Park, where large fishing vessels are banned, although the core no-go zone is relatively small and sometimes fished when unpatrolled. For now, the reefs appear relatively healthy, despite increasing pressure from coral bleaching and other environmental stressors.

During our trip to sapak, we were accompanied by an elderly man with severe hearing loss, Si Nana. On the boat, the men shouted loudly and gestured vividly so he could follow the conversation. The atmosphere on board was relaxed—perfect weather, crystal-blue water, and a good catch.

While resting on the boat and eating raw parrotfish, a young man, Si Kandang, asked why I was not diving much. I explained that I avoided deep dives because of ear pain. He replied that the pain is normal—something one must accept. “Ngei nginey—it is nothing to care about,” as they say in Sama Bajau.

Pain and Biology: Adaptation and Sama Bajau Identity

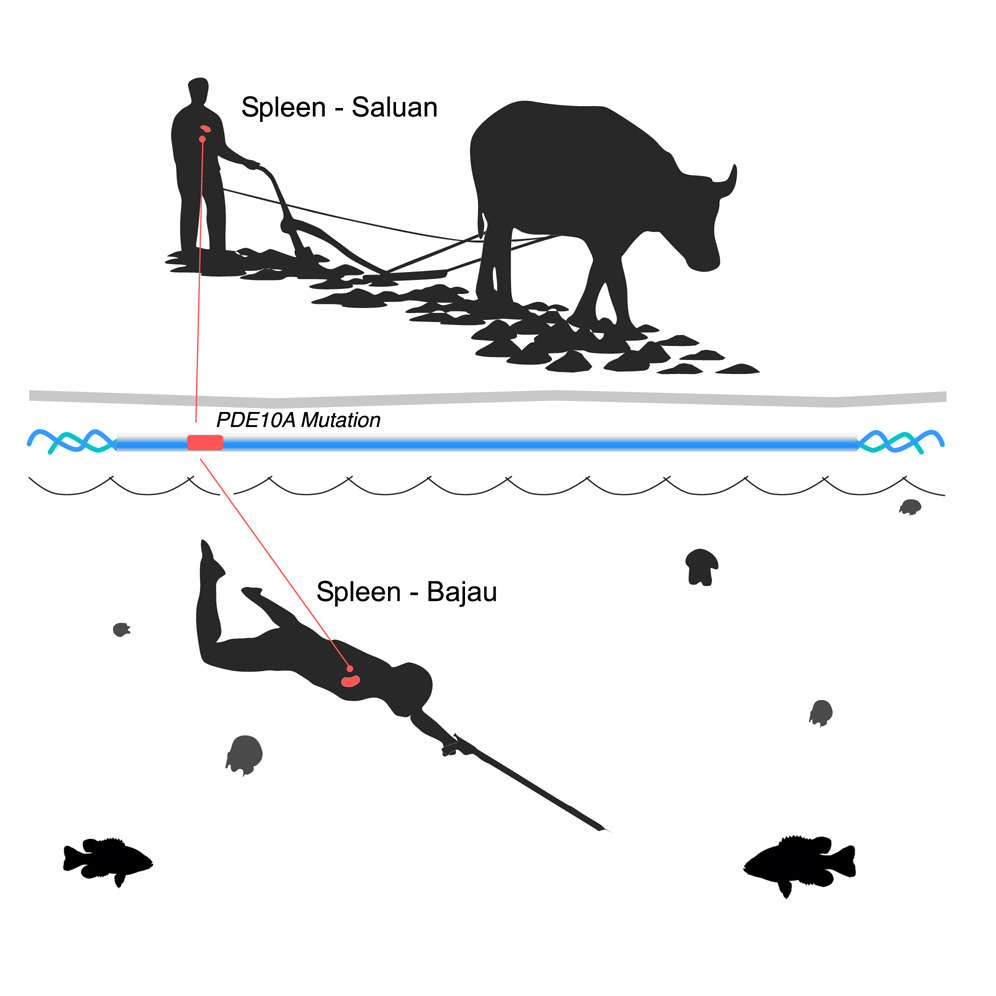

This raises an interesting question: how does the cultural practice of eardrum rupture coexist with genetic adaptations for diving—such as enlarged spleens, as documented in Melissa Ilardo’s study of the Sama Bajau (Ilardo et al., Cell, 2018)?

What we do know is that the Sama Bajau are specifically adapted to a life based on breath-hold diving. Traits such as enlarged spleens—which allow greater oxygen storage and longer dive times—appear to have been favored over generations. These genetic variants exist in all human populations, but they are significantly more common among the Sama Bajau—found in roughly 40% of individuals in the Central Sulawesi community studied by Ilardo and her team.

This pattern suggests long-term selection linked to diving ability. At the same time, Bajau identity is not biologically fixed. People can join Sama Bajau communities, and Sama Bajau individuals can assimilate into neighboring societies—assimilation has historically gone in both directions. It may be that individuals less suited to a diving-based livelihood were more likely to leave, while those skilled at diving remained. This does not necessarily mean that better divers had more children, but rather that they were more likely to remain “Bajau” over generations.

Alongside this biological adaptation exists a strong cultural tradition of teaching children to endure ear pain until the eardrums rupture. This makes diving easier without the need for equalization, but it comes at a cost: increased risk of infection and near-inevitable hearing loss later in life—conditions commonly observed among older Sama Bajau divers.

At first glance, this combination of biological adaptation and bodily damage may seem paradoxical. But if we zoom out, it is not unusual. Painful initiation practices have existed in many societies around the world. While eardrum rupture is not a formal rite of passage, it represents an acceptance of pain as a prerequisite for becoming a capable and respected member of the community. Importantly, this practice has not been limited to men—historically, and still today in places such as Togian, some Sama Bajau women are also highly skilled divers.

Speargun Fishermen and the Strain of a Changing Sea

On the same fishing trip, we were joined by Si Jaharudin, a highly skilled fisherman who had just returned from working with seaweed in Tarakan, near the Malaysian border on Borneo. Although one of the best speargun fishermen in Sampela, he now leaves seasonally to secure a more stable income. At sapak, he carried a large pana speargun and immediately shot a big triggerfish, largely ignoring smaller fish.

That evening, he spoke of his childhood—travelling with his family on a houseboat and staying for weeks at distant reefs.

“It is called pongka,” he said—a time when fishing was abundant, before formal schooling and before reef depletion. That time is gone.

Another day, we were joined by Si Kabei, an expert speargun fisherman who has followed the same method all his life, as did his father before him. He has appeared in many documentaries, including the BBC’s Hunters of the South Seas.

Yet social challenges are becoming increasingly visible, especially in the more traditional and marine-dependent parts of Sampela. Cheap alcohol—such as homemade arak—and widespread betel nut chewing are common. Betel nut stains teeth and lips deep red, creates addiction, and can increase irritability and stress. These pressures add to the burden carried by people like Kabei in a village of more than 1,000 residents, making it harder to maintain stability and put food on the table.

Some parts of the community have stronger ties to wider Indonesian society, offering broader support networks and better access to education. In these households, children are more likely to pursue higher education and diversify their livelihoods. In contrast, the more traditional parts of Sampela remain heavily dependent on the sea—and are therefore more vulnerable.

Fishing is becoming increasingly difficult, and the long-held belief that the sea will always provide is under growing strain. A warming ocean, less predictable weather, and declining fish stocks are changing the conditions people have relied on for generations. The result is a slowly accumulating stress, felt most strongly by those whose lives remain most deeply tied to the sea.

That pressure is not abstract—it is carried by individuals. It falls particularly heavily on resilient men and women such as Kabei, who continue to depend on fishing despite mounting uncertainty. Before leaving, we gave him a laminated photograph of his parents, taken a few years earlier, sitting in their hut. He held it quietly for a long moment, his gaze drifting elsewhere—to another time, and perhaps another way of life.

A Visit to Lohoa

During our stay in Wakatobi, I also visited Lohoa for the first time, accompanied by Pondang. The village is located out on the water, much like Sampela, and lies next to a dense mangrove forest. The atmosphere felt noticeably more relaxed than in Sampela. Many men went shirtless, and almost no women wore hijab—a striking contrast to both Sampela and Topa, especially given that our visit took place during Ramadan.

It felt like travelling back in time, reminding me of Sampela in 2011, when I first arrived there. Walking through Lohoa along the wooden bridges above the water, we saw children playing, jumping in, and swimming joyfully. Dried octopus hung outside a few houses—a common sight on the satellite houses in sapak, where fishers sometimes must wait a long time before selling their catch. In Sampela, octopus can be sold easily to middlemen and transported onward for export.

I also saw men lifting a huge sack of mantis shrimp from a netted pond, where they were kept alive before being sold in nearby Kaledupa—a key source of income for the community.

While spending time in the village, I found myself recalling a conversation I had had with Saiful a few days earlier in Mola. I had asked him whether women were still actively collecting shellfish and whether they were using traditional wooden goggles. He said that only a few still do. Many younger women now try to avoid the sun altogether, seek modern lifestyles, and prefer to stay indoors. Apart from Lohoa, it is only in Sampela where women still commonly collect shellfish—though even there, a clear generational gap is emerging.

When I asked Pondang about the relaxed atmosphere, and about why so many men were shirtless in Lohoa, he suggested it was because they had recently returned from fishing. I suspect it reflects something more habitual—a different rhythm of everyday life. Lohoa felt smaller, cleaner, and calmer, and children moved through the water with ease, diving, swimming, and playing effortlessly.

Reading Wengki Ariando’s Stringing the Islands later confirmed many of my impressions. In the book, he briefly describes Sama Bajau communities across Wakatobi, and Lohoa fits the picture well: only a few people have completed high school, and women and children are deeply involved in making a living from the sea. It is a more traditional community, founded by families from Sampela in the 1970s.

Some Sama Bajau elsewhere in Wakatobi view Lohoa as backward—odd in behavior, speech, or clothing. Yet the sense of joy and calm I felt there was difficult not to be affected by.

Resilience at the Edge of the Sea

When we left Sampela a few days later, at six in the morning, we saw Kabei leading three small boats tied together, moving slowly across the water. Women sat aboard, steering each canoe toward a day of foraging in the shallows. As we passed, Kabei greeted us with a smile, clearly pleased to be heading out to sea.

In many ways, the Sama Bajau are masters of resilience. They cooperate, share, and make use of every available resource. They fish both day and night, read environmental cues, follow the tides, reuse materials, and see what others might call waste as opportunity—the list goes on.

For generations, the Sama Bajau have believed that the sea’s resources are endless—that the ocean will always provide. This worldview may seem naïve from a Western perspective, but it has worked for centuries, offering a sense of security rooted not in savings or property, but in trust in the natural world.

In contrast, we in the West tend to seek security through bank accounts, investments, and future returns. For the Sama Bajau, security has long been something lived and practiced daily, not something abstract and stored away.

As I watched Kabei lead the small flotilla across the water—four boats pulled by a single small engine—I was moved. He is holding on to a traditional way of life, having to add resilience day by day, as that way of life alone is no longer enough in the face of mounting environmental and social pressure.

The corals are slowly dying, yet he believes they will endure.

For him, it is almost impossible to think otherwise.

This belief is not denial, but a way of being—something lived and embodied from childhood.

Diving, moving, and living in the sea offer not only sustenance, but meaning.

And, perhaps, a sense of transcendence.

Tracing Ancient Shorelines: Field Notes from Java on Early Human Evolution

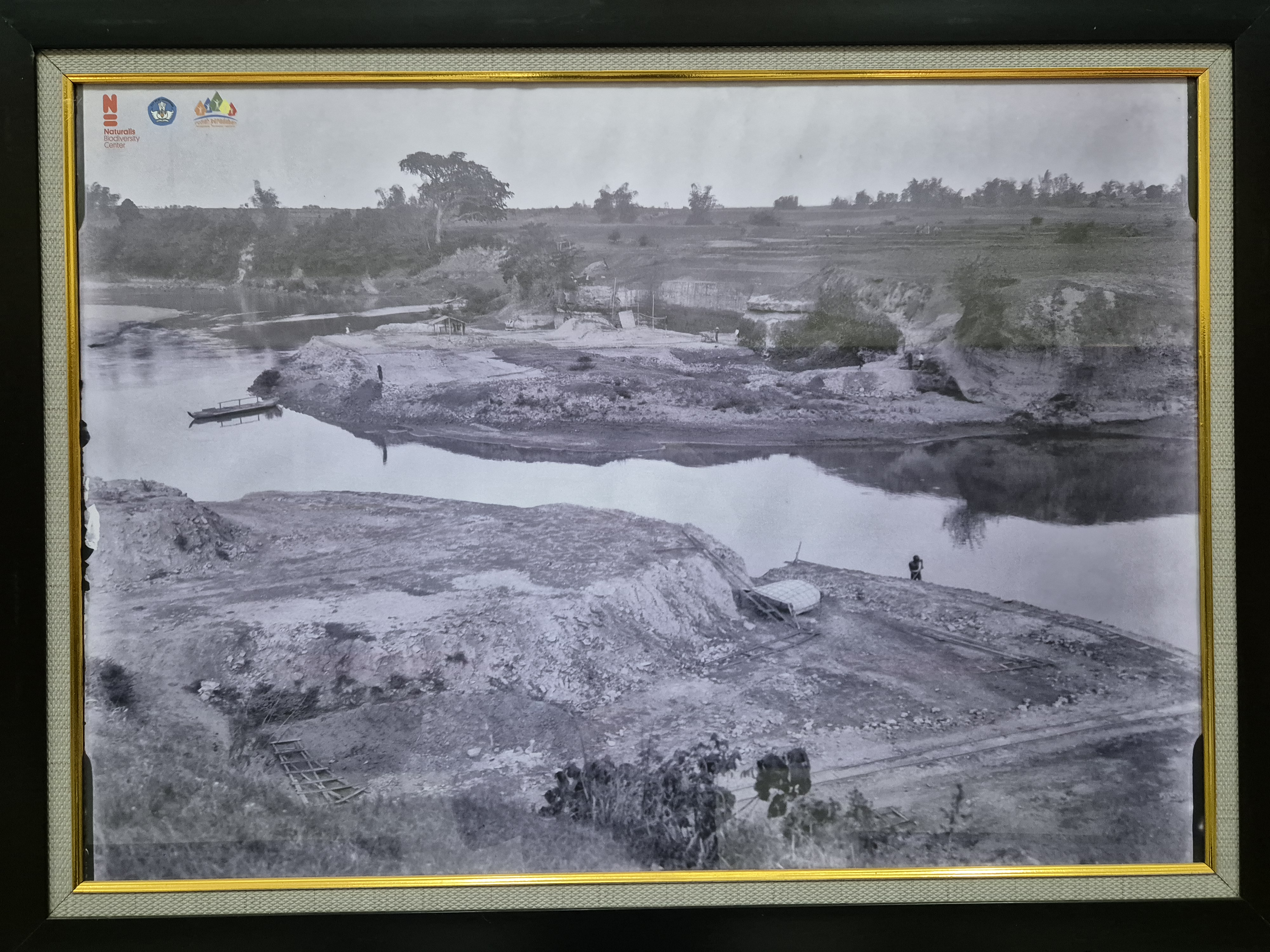

In mid-February, I returned to Southeast Asia—this time to Indonesia—together with Professor Erika Schagatay. At the start of our trip, we met up with Professor José Joordens, a Dutch anthropologist and paleoanthropologist. With her, we visited several excavation sites where she has been working, as well as museums in central Java.

José Joordens became widely known for her work on the engraved freshwater Pseudodon shell from Trinil—a remarkable artifact originally collected by Eugène Dubois and his team in the 1890s and later kept in Dutch museums.

The zig-zag engraving on one of these shells went unnoticed for more than a century. It was in fact archaeologist Stephen Munro who recognized the engraving already in 2007, while examining photographs he had taken of the shell collection in Naturalis Biodiversity Center. The finding was later formally described in 2014. The carving has been dated to between approximately 430,000 and 540,000 years ago, making it the oldest known example of an abstract or symbolic marking created by any human.

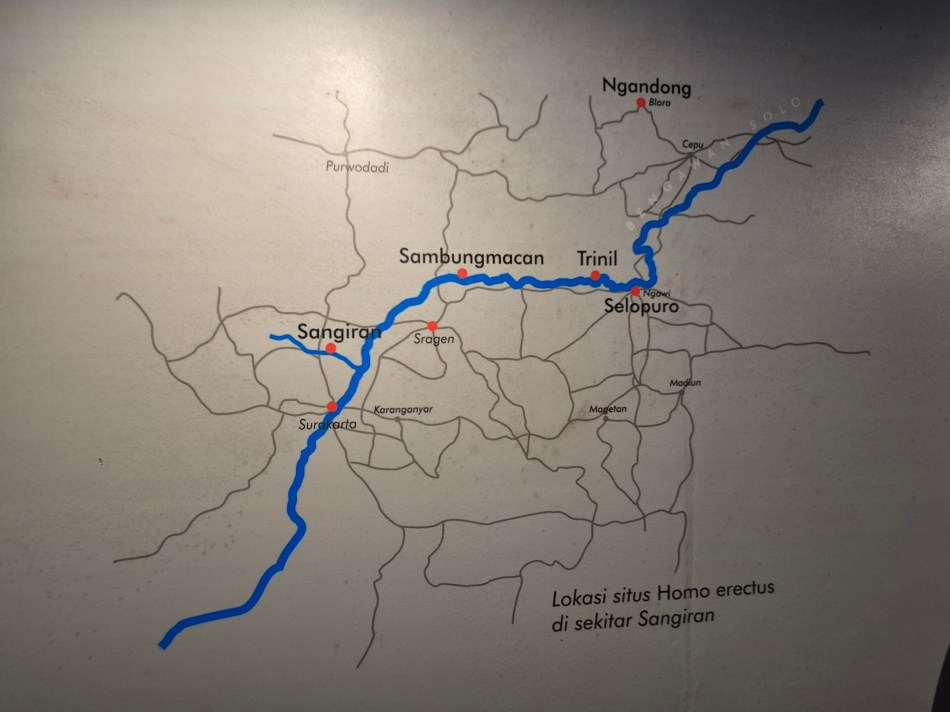

Along the Solo River and the World of Homo erectus

The Solo River basin is one of the richest regions in the world for Homo erectus discoveries. Groups of H. erectus lived along this river system from roughly 2 million years ago until as recently as 100,000 years ago, including the well-known Ngandong population—among the latest surviving Homo erectus known.

During our trip, Erika and José also met with numerous local researchers as part of early planning for a future interdisciplinary project on the Bajau Laut (Sama-Bajau) communities. The project aims to explore diving adaptations from physiological, anthropological, and cultural perspectives.

José has a long-standing interest in the waterside hypothesis and suggests that Homo erectus may have been shallow-water divers and foragers. The argument is supported by evidence such as thick cortical bones, a relatively dense skeleton, potential breath-hold capacity, and repeated associations with shell-bearing or riverine sites. The Trinil shell assemblage is central here, and it has also shown that shells were used as tools. In addition, José has excavated in Kenya’s Turkana Basin—another key region for early hominin interactions with aquatic environments.

Visiting Trinil: Dubois’s Historic Site

One of the highlights of our journey was visiting Trinil, where Eugène Dubois uncovered the first Homo erectus fossils—his famous “Java Man.” It was also here that the engraved shell was found. Local people still consider the site haunted, and many avoid being there at night. During Dubois’s excavations, prisoners were used as laborers, and a number of them died during the work, reportedly chained together and forced to excavate under horrific conditions.

We met long-time collaborators of José who have worked at Trinil for years. We also had access to a back room where numerous remnants, casts, and planning materials are kept, including a copy of the engraved Pseudodon shell. In the surrounding area, we also explored exhibitions and museums that highlight the life and environment of Homo erectus. Standing by the Solo River—where the earliest discoveries of Java Man were made, alongside men fishing with large handheld nets—brought a quiet sense of continuity between past and present.

A Waterside Landscape Two Million Years Ago

Java was a very different place two million years ago. The region was shaped by extensive river systems, lakes, wetlands, and coastal environments, and supported a wide range of mammals adapted to aquatic or semi-aquatic niches—such as hippos, elephants, and other water-associated species. Humans were part of this landscape, and this is also the region where Homo erectus appears to have persisted the longest.

Fossils attributed to Homo erectus appear in Africa at around two million years ago, including recent finds from sites such as Drimolen in South Africa, while the well-known Dmanisi material in Georgia dates to around 1.8 million years ago. In Southeast Asia, the Java record begins around 1.8 million years ago and continues until approximately 100,000 years ago.

Over this immense timespan, H. erectus brains increased in size—a gradual but significant development that may reflect changing environments and a long-term reliance on nutrient-rich aquatic and waterside resources.

In other parts of the world, Homo erectus either evolved into other lineages (for example through Homo heidelbergensis, often discussed as a common ancestor of Homo sapiens, Neanderthals, and Denisovans) or went extinct. Yet on isolated islands in Southeast Asia—such as Flores, Luzon, and Sulawesi—human species appear to have persisted much longer.

Water, Diving, and Human Evolution

Homo erectus had characteristically thick bones and may have been skilled divers. According to some researchers—especially Marc Verhaegen—the species’ history of breath-hold diving shaped both biology and behavior. Verhaegen argues that:

- Homo erectus frequently exploited coastal, riverine, and lake environments.

- Breath-hold diving may have been used to collect shellfish, aquatic plants, and other high-value foods.

- Their relatively heavy and dense skeleton may have functioned as natural ballast during shallow diving.

- In addition to diving, Homo erectus may often have floated on the back while foraging at the surface—somewhat comparable to modern sea otters—allowing extended time in the water with minimal energy expenditure.

- Long-term reliance on aquatic resources could have influenced brain growth and broader physiology.

- Cranial features such as paranasal air sinuses have been discussed in relation to pressure regulation and repeated submersion, though interpretations remain debated.

- Other traits sometimes highlighted include the ability to suck shellfish from shells and hypersensitive fingertips, well suited for detecting hidden prey while foraging underwater.

Homo sapiens later continued to exploit marine foods, which is significant given our need for DHA fatty acids to support a large brain. Although our species eventually became less dependent on diving, technological development likely allowed us to harvest aquatic resources in new and more efficient ways. Coastal foraging probably remained crucial even as our bodies became lighter and more specialized for long-distance walking and endurance running.

Average brain size in the human lineage increased steadily until roughly 300,000–200,000 years ago, after which it appears to have plateaued. A gradual reduction in average brain size becomes visible later, beginning around 50,000 years ago and continuing into more recent prehistory.

Given the high energetic demands of large brains, it seems likely that nutrient-rich foods centered on marine and aquatic resources played an important role during the period of brain expansion. The later reduction in brain size may reflect a gradual decrease in reliance on these resources as humans increasingly diversified their diets and food sources. Many large-brained mammals are closely tied to aquatic food chains during their evolution, which helps explain why the relationship between water, diet, and brain evolution remains such an intriguing topic.

Interestingly, some of the museums we visited—such as the Sangiran Museum Site—explicitly embraced the idea that Homo erectus lived close to water and may represent the earliest island-adapted human. Seeing this interpretation presented so openly was refreshing.

Engraved Shells and Shared Human Cognition

The Trinil shell itself is fascinating. Its zig-zag pattern resembles markings found in other early human contexts, such as the cross-hatched engravings made by early Homo sapiens on pieces of red ochre at Blombos Cave in South Africa (dated to about 73,000 years ago), as well as early Neanderthal engravings, including the cross-hatched markings from Gorham’s Cave in Gibraltar (~39,000 years old).

These similarities raise intriguing possibilities about shared cognitive tendencies—suggesting that geometric pattern-making may reflect deep underlying structures of human and pre-human thought. It also points to a long period when abstract marks existed without figurative art, before a later shift within Homo sapiens—after our species had already been around for more than 200,000 years.

Final Reflections

Traveling with José was inspiring. She is one of the few paleoanthropologists who treats the waterside hypothesis with genuine scientific curiosity, and her background as a marine biologist adds depth to her perspectives.

It is also striking that the earliest known sign of abstract behavior—an intentional engraving—comes not from stone tools or cave walls, but from a freshwater shell, further highlighting the importance of waterside environments in our evolutionary history.

From Wakatobi to the Forefront: XR’s Photo Contest on Water

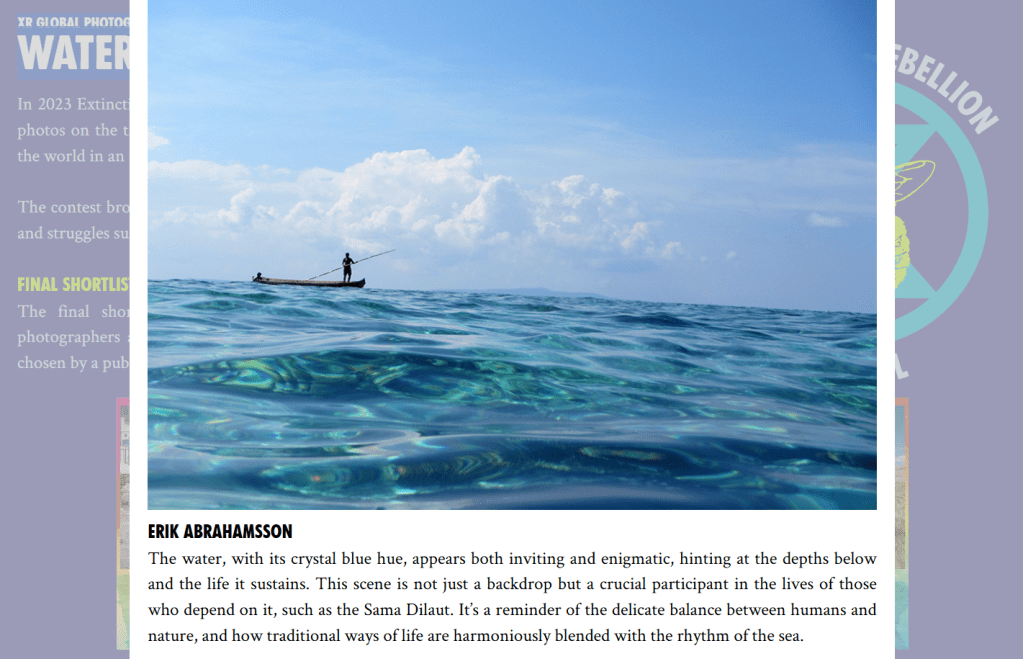

Water is one of our planet’s most precious resources, yet it faces immense challenges worldwide. Extinction Rebellion (XR) organized a global photo competition to raise awareness about these issues, inviting photographers to capture the beauty, struggles, and importance of water. The competition highlighted stories from all corners of the world, showcasing everything from drought-stricken landscapes to communities working to protect this vital resource.

In the end of 2024, XR announced the winners of the competition. While my photo wasn’t among the three winners, it was shortlisted and became part of the final selection for the public vote. The shortlisted photos have since been featured in a traveling exhibition across Europe, visiting cities like Madrid and London, where they continue to inspire and educate audiences.

The photo I submitted was taken in the Wakatobi Islands, Indonesia, depicting a fisherman and his child in a small boat, gliding over crystal-clear blue waters during a net fishing trip inside the Wakatobi National Park. It reflects the deep connection between the Sama Dilaut people and the ocean, celebrating their potential sustainable and harmonious way of life.

You can see the winning and all shortlisted photos here: XR Global Photography Contest – Water Gallery

Below are some of the other photos submitted to the competition:

Meeting Aquatic Pioneers at WADC 2025

Every second year, the World Aquatic Development Conference (WADC) takes place in Lund, gathering experts, enthusiasts, and pioneers from around the globe to celebrate and discuss advancements in aquatics.

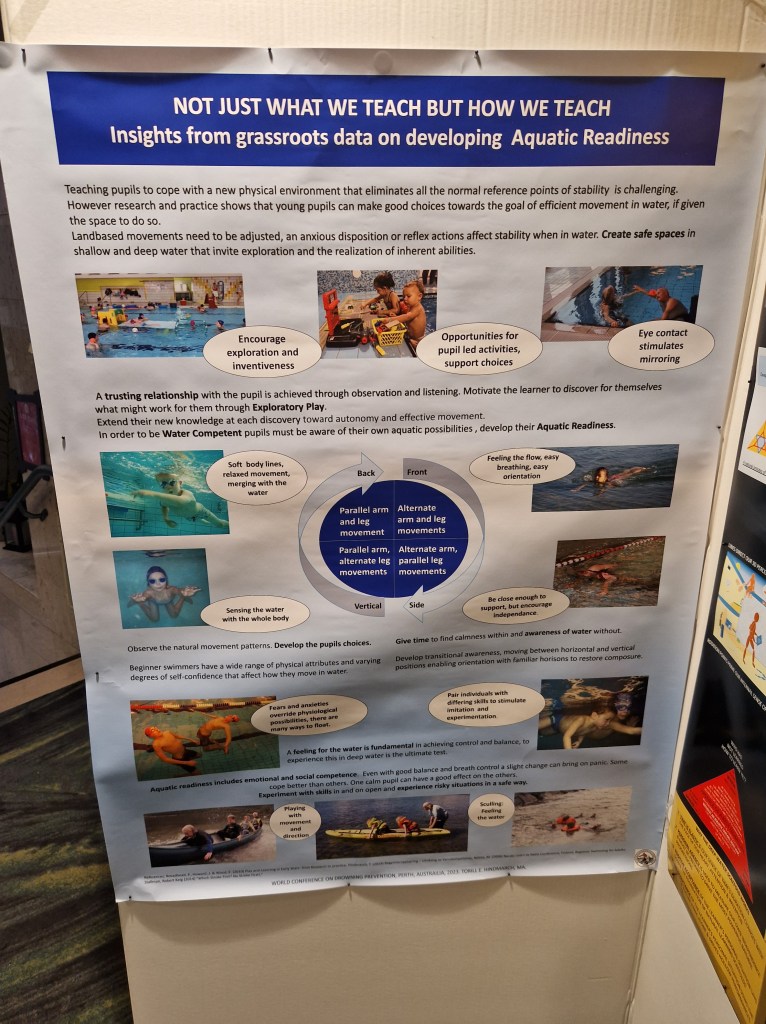

While visiting the poster section of the conference, which took place from 9 to 12 January, I had the privilege of meeting two inspiring persons: Andrea Andrews, a director of The Lifesaving Foundation in Ireland and passionate advocate for safe swimming, and Torill Hindmarch, a pioneer in baby swimming.

While visiting the poster section of the conference, which took place from 9 to 12 January, I had the privilege of meeting two inspiring individuals: Andrea Andrews, a director of The Lifesaving Foundation in Ireland and a passionate advocate for safe swimming, and Torill Hindmarch, a pioneer in baby swimming. Both Andrea and Torill had made insightful contributions to the poster section.

Torill has revolutionized baby swimming through her decades of work rooted in play-based learning and child-centered methods. Her teaching philosophy encourages even the youngest swimmers to engage with water in a safe, joyful, and developmentally appropriate way. As a long-standing advocate for early aquatic education, she has helped shape national swimming programs and inspired countless educators and parents to approach baby swimming with a gentle and empowering focus.

The conference also featured world-class speakers, including Greg Louganis, the legendary diver often regarded as one of the greatest in history. Though I didn’t attend his talk, he is known for sharing fascinating insights into techniques such as “hearing the board,” a skill that demonstrates the precision and mindfulness required to perfect a dive.

It’s a space where innovation meets tradition, where pioneers in baby swimming meet elite expertise, and where the universal language of water continues to inspire and unite people worldwide.

The Cyclical Development: Ice Ages and “Great Leaps” Have Shaped Man

I have previously proposed a Copernican revolution in our understanding of human evolution. In this new article, I outline a broader developmental scheme for humanity, suggesting that we have undergone several great leaps, not just the one occurring 40,000 years ago. Historically, human development has not been about increasing creativity but about enhancing our ability to imitate and replicate behaviors established by our ancestors. Homo sapiens was thus originally a bodily materialization of an old way of life—an old survival strategy—that had been acquired by their predecessor, Homo heidelbergensis.

All standard models in human evolution have been extremely conservative. In their original form, all human species, including our own, have been deeply tradition-bound and produced standardized tools. It was the same Homo erectus who, at the beginning of their existence, manufactured Oldowan tools, later developed the Acheulean culture, and learned to make fire. The same Homo heidelbergensis who, 600,000 years ago, created standardized hand axes and, 400,000 years ago, developed the Levallois technique. The same Neanderthals who, 400,000 years ago, used tools similar to their predecessors, and around 160,000 years ago developed the Mousterian culture, began burying their dead, and created cave paintings. Likewise, Homo sapiens, who 300,000 years ago manufactured standardized Middle Stone Age tools, began 40,000 years ago to create microlithic tools, make sculptures, and spread across the globe.

Our evolution has followed a cyclical pattern, with climate changes like ice ages prompting periods of cultural innovation and biological adaptation. Each time we faced drastic environmental shifts, our latent creative abilities were awakened to develop new survival strategies. Language, which was originally a tool for imitation, became free in this process and created opportunities for symbolic thinking and social organization.

The advent of agriculture drastically changed the scene, as we gained the ability to fundamentally alter our environment. This development sheds new light on our situation today. With the power to reshape nature, there seem to be no limits; we strive to break all boundaries and even aspire to live forever—a sentiment most prevalent in technological hubs like Silicon Valley. In our pursuit to transcend natural constraints, we have become dangerously lost.

You can find the article here: The Cyclical Development: Ice Ages and “Great Leaps” Have Shaped Man

The Paradigm Shaping Our Understanding of Human Evolution

Our understanding of human evolution is not just a scientific endeavor but also a reflection of our self-perception and cultural preconceptions. These elements form part of the underlying paradigm—as discussed by Thomas Kuhn (1962)—or “doxa,” a concept similar to a paradigm introduced by philosopher Pierre Bourdieu (1977), that shapes our understanding of ourselves.

In this context, the theory of evolution, while groundbreaking, has not fundamentally altered our societal structures or self-conception. Instead, it has been adapted to reinforce the cultural and intellectual frameworks that have influenced Western thought for over two millennia, starting from the birth of philosophy.

In our modern, fast-paced culture, we have lost touch with the concept of stability in nature and society. We struggle to imagine a world where multiple generations coexist within the same deep-rooted reality. Our ancestors did not need to be perpetually inventive; rather, their lifestyles were remarkably stable—a fact evidenced by traditional hunter-gatherer societies like the !Kung people (Lee, 1979) and Australian Aboriginals (Tonkinson, 1978). The worldview of these traditional peoples was cyclical rather than linear (Eliade, 1954). In many traditional cultures, humans were regarded as immature and subordinate beings—apprentices to nature, the ultimate teacher (Ingold, 2000). However, over time, this worldview has shifted from being cyclical and holistic to linear, obsessed with the idea of progress and liberation from our natural limitations (Nisbet, 1980).

In previous blog posts, I have discussed the prevailing paradigm in anthropology that emphasizes human intelligence and flexibility, which can make it challenging to consider alternative theories like the aquatic ape theory. In this blog post, we will take a closer look at the deeper perceptions behind the current paradigm of flexible man.

Characteristics of Our Current Paradigm

Our current paradigm is closely intertwined with our views on economic growth and the valorization of entrepreneurship. We project our beliefs about ourselves onto our understanding of evolution, turning it into a form of storytelling. This narrative began with “Man the Hunter” (Lee & DeVore, 1968) and evolved into the “Savannah Hypothesis,” which, after being challenged, transformed into the concept of a mosaic of environments requiring constant flexibility (Potts, 1998). Human intelligence is seen as a trait akin to a lion’s strength or a cheetah’s speed. While animals became faster, more agile, and stronger, humans became smarter. Philosopher Karl Popper summarized this perspective well with his quote: “Our theories die in our place” (Popper, 1963, p. 216).

This paradigm is characterized by deep-seated feelings and assumptions, fundamentally unchanged over centuries—as elaborated by Thomas Kuhn in his concept of paradigms (Kuhn, 1962) and referred to as “doxa” by Bourdieu (1977). This enduring paradigm is not only evident in academic theories but also permeates our literature and cultural narratives. In literature, this perspective is vividly illustrated in Robinson Crusoe (Defoe, 1719), widely regarded as the first modern novel. Stranded alone on a remote island, Crusoe methodically tackles each challenge with resilience and ingenuity, viewing nature as a resource to be mastered. His journey reflects the Enlightenment-era view of man in his authentic state—capable of adapting, solving problems, and exercising rationality to shape his environment (McInelly, 2003). When he meets Friday, Crusoe regards him as a noble savage whom he begins to teach civilized behavior. Eventually, Friday refers to Crusoe as “Master.”

In anthropology, one of the central questions has often been why humans began walking on two legs. This shift to bipedalism was seen as a pivotal development that freed our hands for tool use and allowed for greater flexibility in our behavior (Darwin, 1871). Consequently, much of human evolution has been attributed to our own ingenuity and adaptability, enabling us to become masters of diverse environments.

However, transitioning from quadrupedalism to bipedalism required significant anatomical transformations, particularly in the structure of the knee and pelvis (Lovejoy, 1988). This raises questions about whether the intermediate stages could have been evolutionarily advantageous. Anthropologist Owen Lovejoy suggested that bipedalism arose to enable males to carry food to females, thereby promoting monogamy (Lovejoy, 1981). Such theories reflect our tendency to view human evolution through the lens of our own cultural values. The idea that males would carry food to a single childbearing female reinforces the ideal of monogamy, projecting contemporary social norms onto our ancestors—even though monogamy is not universal among human societies and is not genetically predetermined.

The Influence of Western Philosophy

The roots of our current paradigm can be traced back to ancient Greece. Thinkers such as Plato and Aristotle laid the foundation for the Western emphasis on reason and intellect. Aristotle’s idea of the “rational animal” positioned humans as unique in their capacity for logical thought (Aristotle, trans. 2000).

René Descartes, with his declaration “Cogito, ergo sum” (“I think, therefore I am”) (Descartes, 1641/1996), reinforced the centrality of human reason. Both Descartes and Aristotle were entrenched in the same paradigm that prioritizes rationality as the core of human identity. There has been a consistent thread in the history of philosophy, placing human intellect at the center and viewing it as the essence of humanity. Another manifestation of this enduring paradigm is seen in modern economics, where the “rational actor” model presumes individuals make decisions purely based on logical self-interest, reinforcing the ideal of human rationality.

The aquatic ape theory challenges this paradigm because it explains many human characteristics that anthropologists have traditionally thought did not require explanation. The theory forces us to recognize that, for most of our evolution, we lived in a semi-aquatic environment and were not the flexible entrepreneurs roaming the African terrestrial lands.

Back to the Roots of Evolutionary Theory

Let’s return to the basics of evolutionary theory. Evolution occurs through natural selection when a particular trait is not just successful in one or two generations but remains advantageous over many generations (Darwin, 1859). For evolution to occur, the same traits must be selected repeatedly, which means there must be continuity in development. Simplistically, evolution moves toward an adaptive peak—an optimal state. In evolutionary biology, the concept of an Evolutionarily Stable Strategy (ESS) suggests that there is a way of life, a particular strategy, that outperforms all others in a stable environment (Maynard Smith, 1982).

From this, we can conclude that as long as evolution is occurring, a species must live in the same way for generation after generation. When significant changes happen rapidly, evolutionary development can stagnate because there isn’t sufficient time for advantageous traits to be consistently selected (Gould & Eldredge, 1977). For example, the transition from Homo heidelbergensis to Homo sapiens involved not only an increased brain volume but also a lighter and more agile body structure, smaller jaws and chewing muscles, less robust bones, and more (Rightmire 2008), which is a clear indication that during this time, humans repeated the same living patterns generation after generation.

Human intelligence could not, as Alfred Russel Wallace argued, have arisen solely through traditional evolutionary processes focused on immediate survival advantages (Wallace, 1870). A highly specialized body and a flexible and creative brain do not typically emerge simultaneously under standard evolutionary models; these phenomena seem to exclude each other. The emergence of constantly activated creativity would require a prolonged period of environmental instability—a “continuity of chaos”—but nature rarely presents such conditions over extended timescales. Since our physical form has also undergone significant changes, human intelligence and language must have had original functions beyond mere survival adaptability. During evolution, we were, whether we like it or not, more animal-like.

Challenging the Paradigm

In essence, our understanding of human evolution remains a projection of our cultural self-image, shaped by enduring paradigms that elevate human reason and ingenuity. While a few philosophers like Martin Heidegger and Ludwig Wittgenstein have attempted to push humanity off its self-appointed pedestal, their insights have yet to permeate mainstream thought. Heidegger contended that Western philosophy over the past 2,500 years has gone astray, forgetting the fundamental question of being (Heidegger, 1927/1962). Wittgenstein argued that philosophical problems arise because we become entangled in our own rational language and that we must return to language in its everyday, original form to free ourselves from these confusions (Wittgenstein, 1953).

The new theory of human evolution that I have proposed is based on the idea that evolution has led to increased stability and the reproduction of behavior, making us more animal-like—with creative ability emerging latently as the other side of the coin. This theory correctly aligns with the principles of evolution and goes hand in hand with a more grounded, less anthropocentric view of our place in the natural world.

While physics has profoundly transformed our understanding of the universe—forcing us to accept theories that defy everyday intuition, such as relativity and quantum mechanics, which bear similarities to Zen Buddhism (Capra, 1975)—anthropology has not faced a similar upheaval. The theory of evolution, though it shook religious institutions, did not dramatically alter the narrative. It simply replaced divine creation with natural selection, maintaining the notion of human exceptionalism and behavioral flexibility. The time has come for us to question our long-held assumptions and embrace a paradigm shift that truly reflects the complexities of our evolutionary history.

References

Aristotle. (2000). Nicomachean Ethics (R. Crisp, Trans.). Cambridge University Press. (Original work published ca. 350 B.C.E.)

Bourdieu, P. (1977). Outline of a Theory of Practice (R. Nice, Trans.). Cambridge University Press.

Capra, F. (1975). The Tao of Physics. Shambhala Publications.

Darwin, C. (1859). On the Origin of Species. John Murray.

Darwin, C. (1871). The Descent of Man, and Selection in Relation to Sex. John Murray.

Defoe, D. (1719). Robinson Crusoe. W. Taylor.

Descartes, R. (1996). Meditations on First Philosophy (J. Cottingham, Trans.). Cambridge University Press. (Original work published 1641)

Eliade, M. (1954). The Myth of the Eternal Return: Cosmos and History. Princeton University Press.

Gould, S. J., & Eldredge, N. (1977). Punctuated equilibria: The tempo and mode of evolution reconsidered. Paleobiology, 3(2), 115–151.

Heidegger, M. (1962). Being and Time (J. Macquarrie & E. Robinson, Trans.). Harper & Row. (Original work published 1927)

Ingold, T. (2000). The Perception of the Environment: Essays on Livelihood, Dwelling and Skill. Routledge.

Kuhn, T. S. (1962). The Structure of Scientific Revolutions. University of Chicago Press.

Lee, R. B. (1979). The !Kung San: Men, Women, and Work in a Foraging Society. Cambridge University Press.

Lee, R. B., & DeVore, I. (Eds.). (1968). Man the Hunter. Aldine Publishing.

Lovejoy, C. O. (1981). The origin of man. Science, 211(4480), 341–350.

Lovejoy, C. O. (1988). Evolution of human walking. Scientific American, 259(5), 118–125.

Maynard Smith, J. (1982). Evolution and the Theory of Games. Cambridge University Press.

McInelly, B. C. (2003). Expanding empires, expanding selves: Colonialism, the novel, and Robinson Crusoe. Studies in the Novel, 35(1), 1–21.

Nisbet, R. A. (1980). History of the Idea of Progress. Basic Books.

Popper, K. R. (1963). Conjectures and Refutations: The Growth of Scientific Knowledge. Routledge.

Potts, R. (1998). Variability selection in hominid evolution. Evolutionary Anthropology, 7(3), 81–96.

Rightmire, G. P. (2008). Homo heidelbergensis and Middle Pleistocene hominid evolution in Europe and Africa. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 105(48), 19065–19070.

Tonkinson, R. (1978). The Mardu Aborigines: Living the Dream in Australia’s Desert. Holt, Rinehart and Winston.

Wallace, A. R. (1870). Contributions to the Theory of Natural Selection. Macmillan.

Wittgenstein, L. (1953). Philosophical Investigations (G. E. M. Anscombe, Trans.). Blackwell.

Hard Evidence of Early Human Seafaring and Women’s Role in Marine Foraging

New and fascinating discoveries provide hard evidence for the Aquatic Ape theory, evidence that was not known when Alister Hardy and Elaine Morgan first advocated for this idea. There is now substantial data proving that early humans undertook long maritime journeys, developed unique physiological adaptations, and lived lives closely tied to water. In this blog post, I will examine some of the compelling evidence that supports a semi-aquatic past for humans. These pieces of evidence meet the stringent criteria set by the anthropological community, which demands archaeological proofs for our evolutionary history, rather than merely examining our own bodily adaptations.

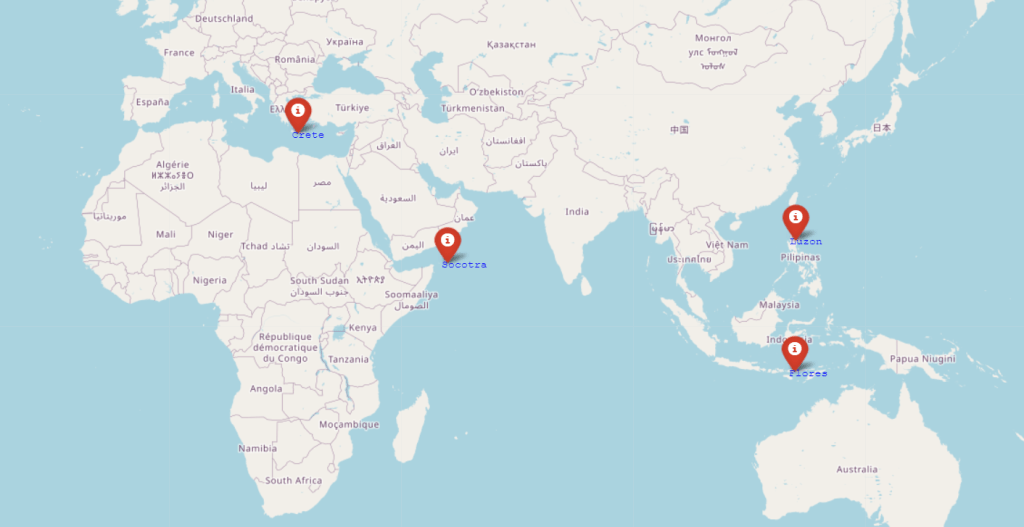

Long Early Maritime Journeys

Early human species undertook impressive sea voyages, as evidenced by discoveries of human fossils and stone tools on distant islands that have been separated from the mainland for millions of years. For instance, Homo sapiens reached Australia about 65,000 years ago, a journey that required crossing at least 70-100 km of open sea from Indonesia, traversing the significant biogeographical barrier known as Wallace Line (O’Connell, Allen, & Hawkes, 2010). Similarly, Homo heidelbergensis or Neanderthals reached Crete around 130,000 years ago, leaving hand axes behind and crossing water distances of approximately 40 km (Strasser et al., 2010).

Even more spectacular are the colonization events of Luzon in the Philippines, Socotra in the Indian Ocean, and Flores in Indonesia. The colonization of Luzon, evident from the discovery of Homo luzonensis dating back 67,000 years, required crossing the Huxley Line, another notable biogeographical barrier, involving a journey of at least 250 km from the nearest landmasses (Detroit et al., 2019). Evidence also suggests that Oldowan toolmakers reached Socotra several hundred thousand years ago, which would have required a sea journey of approximately 80 km from the African coast (Amirkhanov et al., 2009). Additionally, the colonization of Flores, marked by the discovery of Homo floresiensis, also known as the Hobbit, required a journey of around 30-40 km of open sea (Morwood, Oosterzee, & Sutikna, 2007).

It is likely that Socotra, Flores, and Luzon were places where more archaic human species could live relatively undisturbed for long periods. For instance, the discovery of Oldowan tools on Socotra, which first appeared around 2.6 million years ago and were made by the ancestors of Homo erectus, suggests a very ancient colonization of the island (Semaw, 2000; Amirkhanov et al., 2009). The first settlers on Flores and Luzon were also likely from species predating Homo erectus, based on analyses of the fossils of Homo floresiensis and Homo luzonensis, which exhibit some archaic features (Morwood, Oosterzee, & Sutikna, 2007; Detroit et al., 2019). Given that these are all very isolated islands, it is entirely possible that early hominids lived throughout much of Southeast Asia for extended periods but were eventually pushed out when Homo erectus settled in the region, surviving late only on islands far out at sea.

All this evidence indicates that humans have been well-acquainted with aquatic environments for a couple of million years and suggests that humans probably lived scattered throughout the maritime world of the Eurasian coastline. This is also a clear sign that they could build floating structures or boats to undertake these maritime journeys.

Clues from Kalambo Falls

One clue to how these early floating structures might have been constructed can be found at Kalambo Falls in Zambia. Archaeologists have discovered the oldest known wooden structures here, dated to around 476,000 years ago. These structures consist of two interlocking logs joined by an intentionally cut notch. The researchers behind this finding believe the structures were likely used as a stable platform in a wet environment, which may have included use as a raft or dock (Barham et al., 2023).

The preservation of these wooden structures was possible because they became waterlogged, meaning they were submerged in water and saturated, preventing decomposition by creating an anaerobic (oxygen-free) environment (Barham et al., 2023). This remarkable preservation provides further evidence of early humans’ ability to use wood to create structures for aquatic activities.

Surfer’s Ear: Evidence of Aquatic Adaptations in Early Humans

Surfer’s ear, or exostosis, is a bony growth in the ear canal that develops from prolonged exposure to cold water. Research by Trinkaus, Samsel, and Villotte (2019) has shown that a significant percentage of both Neanderthal and early Homo sapiens fossils in Eurasia exhibit this condition. In a study examining 77 fossils with well-preserved ear canals, it was found that these early humans were frequently in cold water environments, likely for marine foraging activities (Trinkaus, Samsel, & Villotte, 2019).

In the study, 48% of the Neanderthal specimens investigated had Surfer’s ear. While it was often difficult to determine their sex, among the identified Neanderthal women, three out of four had this condition (Trinkaus, Samsel, & Villotte, 2019). Similarly, Surfer’s ear was prevalent in Homo sapiens fossils, with approximately 25% of Middle Paleolithic specimens (300,000 to 30,000 years ago) showing the condition. The prevalence was 20.8% during the Early/Mid Upper Paleolithic (50,000 to 30,000 years ago) and dropped to 9.5% in the Late Upper Paleolithic (30,000 to 10,000 years ago), indicating a change in lifestyle (Trinkaus, Samsel, & Villotte, 2019).

Interestingly, in the 19 sexable Early/Mid Upper Paleolithic Homo sapiens specimens, Surfer’s ear was present in 16.7% of males and 28.6% of females. This suggests that more women than men exhibited this condition in early Homo sapiens (Trinkaus, Samsel, & Villotte, 2019). These findings support the hypothesis that women, due to their thicker layer of subcutaneous fat, were better suited to spending extended periods in water and were likely more involved in diving activities. This evidence highlights the significant role aquatic environments played in the lives of early humans.

Moreover, findings from Panama show that even people living in warm environments can develop Surfer’s ear when they engage in deep diving where the water is colder. This observation is supported by the analysis of fossils dating back thousands of years (Arias-Martínez et al., 2019), further emphasizing the connection between human activity and aquatic environments across different climates and time periods.

Conclusion

These pieces of evidence collectively paint a compelling picture of how early humans thrived in and around water. From navigating long distances over open seas to developing physiological adaptations to cold water environments, much also indicates that women were perhaps more involved than men in diving activities during this time.

As we uncover more about our past, it becomes clear that our relationship with water has profoundly shaped our evolution. These findings not only challenge previous notions about early human behavior but also open new avenues for understanding the complexities of our development. The future of exploring our aquatic heritage lies in continued research and the growing field of underwater archaeology, promising even more fascinating discoveries.

Literature

Amirkhanov, K. A., Zhukov, V. A., Naumkin, V. V., & Sedov, A. V. (2009). Эпоха олдована открыта на острове Сокотра. Pripoda, 7.

Arias-Martínez, L., González-Reimers, E., Velasco-Vázquez, J., Santolaria-Fernández, F., & Hernández-Moreno, M. (2019). Auditory exostoses and their relationship to environmental factors in the pre-Hispanic Canary Islands. American Journal of Physical Anthropology. https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/abs/10.1002/ajpa.23757.

Barham, L., et al. (2023). Earliest Evidence of Structural Use of Wood at Kalambo Falls. Nature. https://www.nature.com/articles/s41586-023-06557-9.

Detroit, F., Mijares, A. S., Piper, P., Grün, R., Bellwood, P., Aubert, M., … & Zeitoun, V. (2019). A new species of Homo from the Late Pleistocene of the Philippines. Nature, 568(7751), 181-186.

Morwood, M. J., Oosterzee, P. V., & Sutikna, T. (2007). The Discovery of the Hobbit: The Scientific Breakthrough that Changed the Face of Human History. Random House.

O’Connell, J. F., Allen, J., & Hawkes, K. (2010). Pleistocene Sahul and the Origins of Seafaring. Cambridge Archaeological Journal, 20(1), 69-84. doi:10.1017/S0959774310000055.

Strasser, T. F., Panagopoulou, E., Runnels, C. N., Murray, P. M., Thompson, N., Karkanas, P., … & Coleman, J. (2010). Stone Age seafaring in the Mediterranean: evidence from the Plakias region for Lower Palaeolithic and Mesolithic habitation of Crete. Hesperia: The Journal of the American School of Classical Studies at Athens, 79(2), 145-190.

Trinkaus, E., Samsel, M., & Villotte, S. (2019). External auditory exostoses (Surfer’s ear) in the human fossil record: A proxy for behavioral adaptations to aquatic resources. PLOS ONE, 14(8): e0220464. https://journals.plos.org/plosone/article?id=10.1371/journal.pone.0220464.

A New Perspective on Marx’s Theory of Alienation and Human Creativity

Karl Marx’s insights into human nature and alienation remain profoundly relevant today. His early writings described a human nature fundamentally at odds with the capitalistic system because their creative ability came into the possession of others. Marx’s ideas highlighted the disconnection individuals felt from their labor, their products, and ultimately themselves.

The new understanding of human development, as discussed in my previous articles, sheds new light on creativity and alienation. Throughout evolution, tools and technology helped humans establish themselves in environments where they were not biologically adapted. Intertwined with our evolution, tools and technology have significantly shaped our creative ability. This adaptation led to significant brain development, enabling us to imitate and reproduce behaviors; and in situations of big changes make us able to invent. Tools changed our hands, particularly the thumb grip, and enhanced qualities such as increased working memory, spatial cognition, and improved coordination and dexterity.

Additionally, it spurred the development of language, which originally was structured behavior and what we can describe as embodied culture. In this text, I will explore the foundations of human creation and see what we can learn about alienation from a modern perspective. How does our evolutionary journey illuminate the causes of alienation in today’s world?

Creation as a Mental Process

Creation is fundamentally a mental process where an image or idea from the mind is projected onto external reality. When humans create, we transfer a mental image onto reality, projecting a part of ourselves onto the material world. This process of creation is not only about material production but also about expressing and shaping human identity, culture, and mind. Creation is inherently a spiritual act, where the materialization of mental images connects us deeply with our inner selves and the universe around us.

This understanding is central to comprehending how humans have historically used language and tools in a way that does not distinguish between body and mind. This unity reflects a state where language and tool use were inseparable, representing a holistic way of interacting with the world. Early Homo sapiens were remarkably stable and conservative in their tools and material culture, with no evidence of art or symbolic representation for more than half of their existence. This suggests that their interaction with the world was primarily practical and utilitarian, rather than expressive or decorative.

This unity is also reflected in nearly all mythologies that describe an original undifferentiated state where humans and nature were inseparable. In other words, the human brain fostered a sense of connectivity enabled through our mind-tool relationship with the world. This holistic interaction with our environment highlights the deep-rooted integration of cognitive and physical processes in human development.

The neuroscientist Michael Arbib and the paleoanthropologist André Leroi-Gourhan have both contributed to our understanding of this connection. Arbib has explored how grasping for material objects and the role of mirror neurons laid the foundation for what later became language as we know it today (Arbib, 2012). Arbib also claims that human language arose in a different part of the brain than the so-called primate calls. Leroi-Gourhan, on the other hand, has highlighted the role of technology as a kind of “membrane” that mediates the relationship between humans and their surroundings, demonstrating the deeply integrated role of technology in human culture and cognitive development (Leroi-Gourhan, 1993).

Marx’s Philosophy of Creation and Alienation

Karl Marx saw humans as creative beings who actively reshaped the world around them, constantly interacting with their environment. Our new understanding of evolution and creation provides a fresh and solid foundation for Marx’s thinking about human nature and alienation. The insight that language and tool use were intertwined from the beginning reveals the profound nature of creation—it is not just a reflection of the inner world but also a way to physically and actively shape our environment. There is an intricate interplay between human creation and the environment, each influencing and transforming the other, which in turn contributes to societal change and change of mind.

Marx recognized that when humans’ creative power is taken from them and transformed into something alien and unknown, it leads to deep alienation (Marx, 1959). It is not just that everything becomes a commodity in capitalism; it is that we lose a part of ourselves when our work—our materialized self—is taken from us. According to Marx, when we create, a part of our soul is materialized in the product. When this product, this piece of our soul, does not belong to us but to someone else through private property regulations and monetary transactions, something in us is lost. Marx originally philosophized about this, describing how this deprivation makes the individual feel alienated from the products of their own labor and ultimately from themselves. This separation is deeply harmful to both individual well-being and the health of society at large. In this stage, people function only in their most basic physiological capacities, devoid of soul, creativity, and happiness.

Originally, this creation involved monotonous repetitive movements that did not include symbols. However, during the cognitive revolution, which occurred between 50,000 and 75,000 years ago, language became unrestrained and started to incorporate symbols, transforming the way humans thought and created. Despite this transformation, creation has always remained fundamentally a spiritual practice. It has always been a way to reconnect with the original sense of connectivity and unity of body and soul.

The Body as Master of the Brain

Recent research offers new insights into Karl Marx’s ideas on alienation. Guy Claxton, a psychologist and cognitive scientist, has challenged the conventional view of the brain as the primary controller of human activity. He posits that the brain should be seen as a servant to the body, emphasizing the crucial role of physical interaction in cognitive processes (Claxton, 2015). This perspective highlights the importance of bodily experiences and actions in our cognitive development and creative expression, a concept that is increasingly acknowledged in the field of embodied cognition.

Claxton also argues that a significant part of our thinking resides in our hands. Monotonous creation, such as crafting or art, can calm and focus the mind. This process involves a dialogue between mind and matter, where mental concepts are projected and transformed through physical actions. This idea supports Marx’s view that labor, when aligned with one’s essence, becomes a source of fulfillment.

Living with Material Technology

The influential anthropologists Marshall Sahlins has posited that traditional and indigenous peoples often lead lives of relative abundance and satisfaction through their deep integration with their material environment (Sahlins, 1972). This idea challenges modern assumptions about material wealth and fulfillment, suggesting that human well-being is closely tied to a harmonious relationship with one’s surroundings. All traditional peoples have more or less created their own material world, embodying a symbiotic relationship with their environment that fosters both sustainability and contentment.

The Bajau Laut people are a modern example of a group that still lives this way today. They exemplify how deeply satisfying it can be to live in harmony with one’s material technology. By directly creating their world through interactions with their environment, they demonstrate a way of life where technology and the environment are not foreign or separate from daily human life but rather an integrated part of it. Much of what they use in their daily lives, such as boats, fishing gear, goggles, and even their houses, are created with their own hands.

This form of direct engagement in creating and shaping one’s world is reflected in various indigenous and traditional societies worldwide and is central to human fulfillment. The practice of crafting and using tools that are intimately connected to their environment not only meets practical needs but also reinforces a profound sense of identity and purpose. By examining the lifestyles of the Bajau Laut and other indigenous groups, we gain insight into the essential human drive to create and the deep satisfaction derived from living in harmony with the material world.

The Abundance of Soul in Capitalism

Marx also briefly touched on the alienation that capitalists themselves experience, who, despite accumulating wealth, lose touch with their human nature. In a capitalist framework, everything, including creativity and human interactions, becomes a means to an end, breaking the fundamental connections with the natural world, community, and oneself. The purpose of existence, which once involved meaningful engagement and fulfilment, is overshadowed by the relentless pursuit of wealth. This detachment creates an insatiable state of lack, revealing a profound societal alienation.

In such a society, our lives become tools for accumulation. The primary role is to accumulate money, which can be transformed into anything, giving it a powerful allure. This drive shifts our existence towards the relentless pursuit of wealth, energy, and material gains, transforming our very essence into different forms of capital. This can lead to an overwhelming abundance of ‘soul’—the materialized product of others’ hard work and alienation. However, this influx of material wealth and success does not satisfy; instead, it exacerbates the sense of emptiness and detachment.

As we become overwhelmed by this materialized soul, alienation also arises among the privileged, leading to an insatiable desire for more. This craving for more is starkly visible in Silicon Valley, where many tech entrepreneurs are now pursuing projects to unlock eternal life. This illustrates the complex and pervasive nature of alienation in modern capitalist society, where life becomes a tool for accumulation, and an abundance of material wealth fuels a deeper void.

Conclusion

Our exploration into the foundations of human creation, drawing from the perspectives of early Homo sapiens, Karl Marx, and indigenous peoples, reveals that reconnecting with our creative and spiritual essence is essential for overcoming alienation. The capitalist system’s relentless pursuit of wealth and commodification of life leads to a profound sense of disconnection and emptiness. This alienation affects not only workers but also capitalists, who remain estranged from their human nature despite their material success.

The earliest Homo sapiens were guided by their bodily experiences, which formed a kind of embodied culture and a deeply spiritual experience, where doing and thinking were inseparable from both hand and mind. This historical perspective shows that human creation and physical interaction have always been intertwined, providing a sense of unity and fulfillment that is often missing in modern capitalist societies.

We see this clearly in Silicon Valley, where the quest for more inventions and transcending human limits seems insatiable. Here, people are even pursuing projects to unlock eternal life, which is a profound sign of alienation. To counteract this, we must embrace the inherent satisfaction found in simplicity and monotonous creative expression. Indigenous peoples exemplify living in harmony with their material environment, fostering both sustainability and contentment.

Through the act of creation—whether through art or crafting—we engage in a meaningful dialogue with the world, connecting the spiritual and physical realms and allowing for genuine self-expression. Indigenous cultures, in particular, demonstrate the deep fulfillment that comes from integrating creative practices with everyday life, highlighting the importance of this balance.

Ultimately, we must recognize the limits of our needs and the futility of overindulgence. The constant striving for more only deepens the void within us. By choosing to be satisfied with less and focusing on reconnecting with our creative and spiritual roots, we can find true fulfillment and mitigate the alienation pervasive in modern society. Embracing a simpler, more connected way of living, as seen in indigenous cultures, offers a path to overcoming the deep-seated disconnection that capitalism perpetuates.

The ultimate alienation will not lead to the end of death; rather, it will lead to our dissolution.

References

Arbib, Michael. “How the Brain Got Language: The Mirror System Hypothesis.” Oxford University Press, 2012.

Leroi-Gourhan, André. “Gesture and Speech.” MIT Press, 1993.

Claxton, Guy. “Intelligence in the Flesh: Why Your Mind Needs Your Body Much More Than It Thinks.” Yale University Press, 2015.

Sahlins, Marshall. “Stone Age Economics.” Aldine-Atherton, 1972.

The Displacement of Bajau Laut: A Lost Haven in Sabah

In a contentious move aimed at allegedly enhancing security and curbing cross-border crime, Malaysian authorities have evicted over 500 Sama Dilaut individuals from their homes within Tun Sakaran Marine Park off the coast of Semporna, Sabah, starting on June 4. The Sama Dilaut saw their coastal stilt huts demolished or burned by enforcement officials, sparking a wave of criticism from rights groups and local activists.

Historical and Cultural Significance

The Sama Dilaut have been part of the marine landscape in Semporna for centuries. Their picturesque traditional settlements have attracted global attention for their unique architectural style and seemingly harmonious coexistence with nature. These settlements were not just homes but symbols of eco-living and sustainable practices, resonating deeply with any human. Bod Gaya, in particular, was renowned for its lovely stilt houses located next to a mountain top inside the Marine Park, as well as its boat-building activities of both houseboats and dugout canoes, a craft that has been passed down through generations.

Government’s Stance

Sabah’s Minister of Tourism, Culture, and Environment, Christina Liew, defended the eviction operation, stating that it was necessary to uphold the sovereignty of the country’s laws. According to authorities, unauthorized activities such as illegal fishing, building without permits, and unpermitted farming within protected areas managed by Sabah Parks necessitated the crackdown. She also highlighted security concerns, including cross-border crime.

Liew claimed that some homeowners might have intentionally burned their own houses to garner sympathy and virality on social media. According to the authorities, notices had been sent to 273 unauthorized settlements, and between Tuesday and Thursday, June 4 to 6, no less than 138 structures were demolished inside the Tun Sakaran Marine Park.

Humanitarian Concerns and Advocacy