Staying with the Sama Bajau: Life, Change, and Resilience at Sea

During the trip to Indonesia we also visited Sulawesi and several Bajau communities. Already in Jakarta I met a Sama Bajau man named Yakub, author of Anak Atol (literally “a child of an atoll”), a book describing the childhood of a boy growing up on a small coral island—an experience shared by many Bajau. I asked him about the practice of intentionally rupturing the eardrums, and he explained that it is ”harus”—it is a must—for those who want to make a living from diving. It is truly an initiation rite!

Between Reef and Open Sea: Life and Fishing in Topa

After leaving Java, we travelled to the island of Buton in southeast Sulawesi, where we visited the Sama Bajau community of Topa in Kamaru—a place Erika had first visited back in 1988 during her earlier travels in Southeast Asia.

In Topa, we followed on local fishing trips. Fishing had not been good lately: fewer fish were being caught, and our usual speargun fishing trips were not very successful. While we were fishing, a nearby family group was using a compressor while searching the coral wall for large and lucrative fish. As a matter of fact, many skilled freedivers – as for example Si Mansor – have now shifted toward offshore tuna fishing, using hook and line far out at sea—a more lucrative livelihood than spearfishing coral reefs. They can travel for hours to reach tuna grounds and stay at sea for long periods. Some even remain on the boat for months during the right season.

Others remain closer to the community, choosing either high-investment fishing—using compressors to stay deeper for longer periods and target high-value fish—or very low-cost methods without motorized boats, where small but sufficient profits are made through skilled diving, such as catching mantis shrimp, which requires experience and precision but can generate good income.

These strategies are often mixed: intensive trips during certain seasons, combined with more traditional fishing close to home to meet household needs while staying in the village.

The fishermen of Topa voiced frustration over Sama Bajau from the Kendari region who enter the area with speedboats and use fish bombs, which has caused noticeable declines in reef fish. Despite this, during a visit to the nearby village of Lasalimu, we were greeted by dolphins—a beautiful reminder of what still persists.

We also visited the grave of Husimang, who had hosted Erika already in 1988. His wife—still alive—joined us, along with their children and grandchildren, as we climbed the hills together.

Clams, Recycling, and Creative Survival

During our visit to Lasalimu, we met a woman selling the meat of giant clams. One whole clam sold for only 25,000 rupiah—barely more than 1.5 USD—shockingly low for a species protected since 1985.

In the village, we met a group of children wearing traditional wooden goggles who had been collecting shellfish. They proudly showed us their catch and later followed us to the pier, happily throwing themselves into the water, diving and swimming with ease.

Back in Topa, we observed small but ingenious forms of recycling, such as chairs made from used motorcycle wheels. Our host was buying various shells, including abalone, to sell in bulk in Baubau, where they are used for jewelry or clothing buttons. People continually find creative solutions and new livelihoods in a world where fish are becoming increasingly scarce.

Across Borders: Mola, Australia, and the Politics of the Sea

After our stay in Topa, we travelled onward to Wangi-Wangi in Wakatobi National Park, staying close to Mola—with a population of around 8,000, probably the largest Sama Bajau community not only in Sulawesi but in Indonesia.

Here I met an old acquaintance, Saiful, a Sama Bajau man who had learned English during a year spent in an Australian prison for illegal fishing. One night, he picked me up in Wanci town on his motorcycle, and we rode together to Mola for coffee.

Saiful’s brother-in-law joined us—married to Saiful’s sister. He is Bugis, but now fully integrated into the Sama Bajau community; I could tell no difference.

“He is skilled in hook-and-line fishing,” Saiful said.

We spoke about Saiful’s experiences in Australia, which reminded me of a conversation I had had in Topa just a few days earlier with an elderly man who had travelled to Australia many times and had been arrested and sent to Bali. He told me that some younger Sama Bajau even hoped to be caught, believing Australia offered opportunity—though in reality, they would usually be sent to Bali because they were underage.

In the Riau Islands, the Bajau community of Pepela was founded by migrants from southeast Sulawesi, and strong social and kinship ties remain between Pepela and villages such as Mola and Mantigola. Shark fishing has become increasingly difficult, and many men no longer travel there, yet the networks connecting these communities remain strong.

Anthropologist Natasha Stacey has written extensively about Sama Bajau fishing activities in Australian waters. In Boats to Burn, she describes how the construction of traditional perahu lambo sailing vessels persisted in southeast Sulawesi because Australian law, for a time, allowed only traditional boats—not motorized vessels—into its fishing zones.

This policy inadvertently preserved a boatbuilding tradition that had already disappeared in many other Indonesian Sama Bajau communities. It is a clear example of how global politics and national borders can shape—and sometimes sustain—local practices, technologies, and ways of life.

Life Along the Reef: From Sampela to Satellite Houses

A few days later, we arrived in Sampela, where we again stayed with Pondang, in the traditional stilt houses—now used as homestays—that we once helped construct. For two days, we joined local speargun fishermen on the surrounding coral reefs. Fishing was better than in Topa, but still far from what it used to be, despite Sampela’s proximity to an extensive reef system.

We also travelled to the outer reefs known as sapak, where some Sama Bajau have built temporary stilt houses—so-called satellite houses—for distant fishing. Here, fishing was noticeably better, with larger fish more common than near the main community. The area benefits from its location inside Wakatobi National Park, where large fishing vessels are banned, although the core no-go zone is relatively small and sometimes fished when unpatrolled. For now, the reefs appear relatively healthy, despite increasing pressure from coral bleaching and other environmental stressors.

During our trip to sapak, we were accompanied by an elderly man with severe hearing loss, Si Nana. On the boat, the men shouted loudly and gestured vividly so he could follow the conversation. The atmosphere on board was relaxed—perfect weather, crystal-blue water, and a good catch.

While resting on the boat and eating raw parrotfish, a young man, Si Kandang, asked why I was not diving much. I explained that I avoided deep dives because of ear pain. He replied that the pain is normal—something one must accept. “Ngei nginey—it is nothing to care about,” as they say in Sama Bajau.

Pain and Biology: Adaptation and Sama Bajau Identity

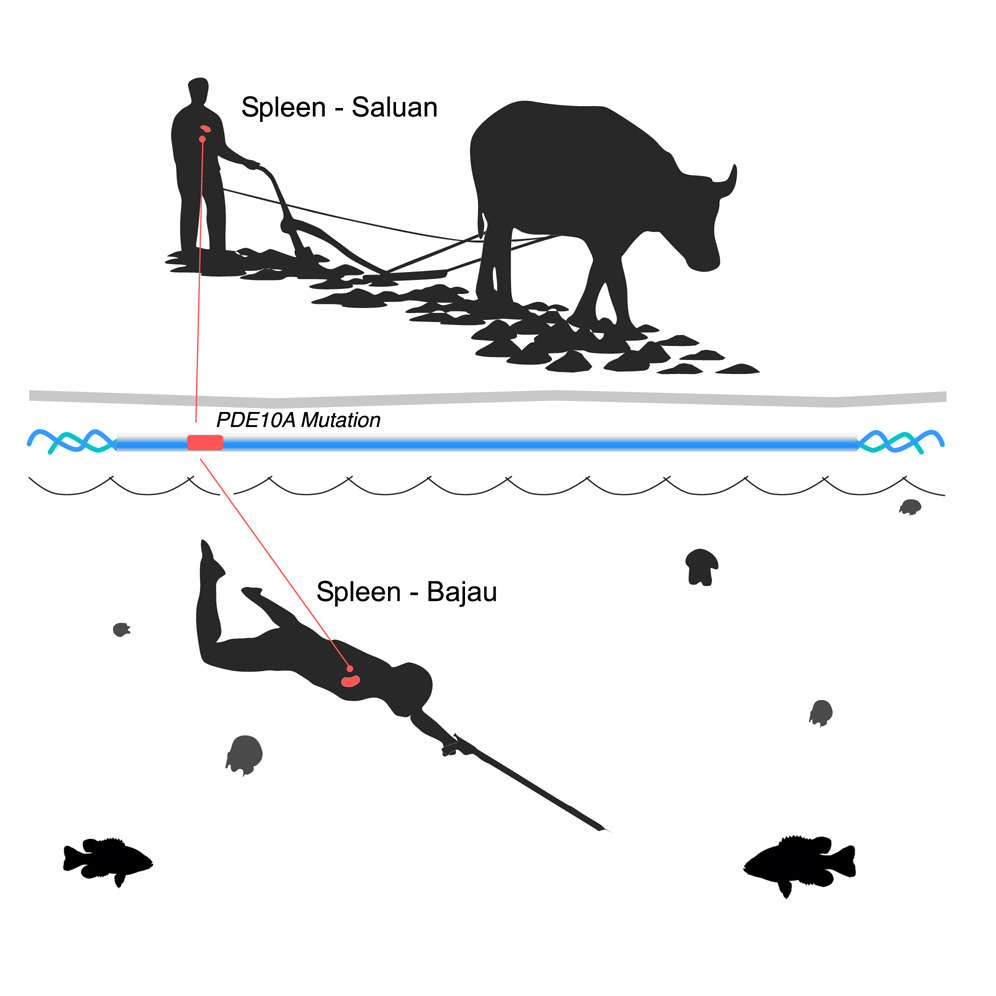

This raises an interesting question: how does the cultural practice of eardrum rupture coexist with genetic adaptations for diving—such as enlarged spleens, as documented in Melissa Ilardo’s study of the Sama Bajau (Ilardo et al., Cell, 2018)?

What we do know is that the Sama Bajau are specifically adapted to a life based on breath-hold diving. Traits such as enlarged spleens—which allow greater oxygen storage and longer dive times—appear to have been favored over generations. These genetic variants exist in all human populations, but they are significantly more common among the Sama Bajau—found in roughly 40% of individuals in the Central Sulawesi community studied by Ilardo and her team.

This pattern suggests long-term selection linked to diving ability. At the same time, Bajau identity is not biologically fixed. People can join Sama Bajau communities, and Sama Bajau individuals can assimilate into neighboring societies—assimilation has historically gone in both directions. It may be that individuals less suited to a diving-based livelihood were more likely to leave, while those skilled at diving remained. This does not necessarily mean that better divers had more children, but rather that they were more likely to remain “Bajau” over generations.

Alongside this biological adaptation exists a strong cultural tradition of teaching children to endure ear pain until the eardrums rupture. This makes diving easier without the need for equalization, but it comes at a cost: increased risk of infection and near-inevitable hearing loss later in life—conditions commonly observed among older Sama Bajau divers.

At first glance, this combination of biological adaptation and bodily damage may seem paradoxical. But if we zoom out, it is not unusual. Painful initiation practices have existed in many societies around the world. While eardrum rupture is not a formal rite of passage, it represents an acceptance of pain as a prerequisite for becoming a capable and respected member of the community. Importantly, this practice has not been limited to men—historically, and still today in places such as Togian, some Sama Bajau women are also highly skilled divers.

Speargun Fishermen and the Strain of a Changing Sea

On the same fishing trip, we were joined by Si Jaharudin, a highly skilled fisherman who had just returned from working with seaweed in Tarakan, near the Malaysian border on Borneo. Although one of the best speargun fishermen in Sampela, he now leaves seasonally to secure a more stable income. At sapak, he carried a large pana speargun and immediately shot a big triggerfish, largely ignoring smaller fish.

That evening, he spoke of his childhood—travelling with his family on a houseboat and staying for weeks at distant reefs.

“It is called pongka,” he said—a time when fishing was abundant, before formal schooling and before reef depletion. That time is gone.

Another day, we were joined by Si Kabei, an expert speargun fisherman who has followed the same method all his life, as did his father before him. He has appeared in many documentaries, including the BBC’s Hunters of the South Seas.

Yet social challenges are becoming increasingly visible, especially in the more traditional and marine-dependent parts of Sampela. Cheap alcohol—such as homemade arak—and widespread betel nut chewing are common. Betel nut stains teeth and lips deep red, creates addiction, and can increase irritability and stress. These pressures add to the burden carried by people like Kabei in a village of more than 1,000 residents, making it harder to maintain stability and put food on the table.

Some parts of the community have stronger ties to wider Indonesian society, offering broader support networks and better access to education. In these households, children are more likely to pursue higher education and diversify their livelihoods. In contrast, the more traditional parts of Sampela remain heavily dependent on the sea—and are therefore more vulnerable.

Fishing is becoming increasingly difficult, and the long-held belief that the sea will always provide is under growing strain. A warming ocean, less predictable weather, and declining fish stocks are changing the conditions people have relied on for generations. The result is a slowly accumulating stress, felt most strongly by those whose lives remain most deeply tied to the sea.

That pressure is not abstract—it is carried by individuals. It falls particularly heavily on resilient men and women such as Kabei, who continue to depend on fishing despite mounting uncertainty. Before leaving, we gave him a laminated photograph of his parents, taken a few years earlier, sitting in their hut. He held it quietly for a long moment, his gaze drifting elsewhere—to another time, and perhaps another way of life.

A Visit to Lohoa

During our stay in Wakatobi, I also visited Lohoa for the first time, accompanied by Pondang. The village is located out on the water, much like Sampela, and lies next to a dense mangrove forest. The atmosphere felt noticeably more relaxed than in Sampela. Many men went shirtless, and almost no women wore hijab—a striking contrast to both Sampela and Topa, especially given that our visit took place during Ramadan.

It felt like travelling back in time, reminding me of Sampela in 2011, when I first arrived there. Walking through Lohoa along the wooden bridges above the water, we saw children playing, jumping in, and swimming joyfully. Dried octopus hung outside a few houses—a common sight on the satellite houses in sapak, where fishers sometimes must wait a long time before selling their catch. In Sampela, octopus can be sold easily to middlemen and transported onward for export.

I also saw men lifting a huge sack of mantis shrimp from a netted pond, where they were kept alive before being sold in nearby Kaledupa—a key source of income for the community.

While spending time in the village, I found myself recalling a conversation I had had with Saiful a few days earlier in Mola. I had asked him whether women were still actively collecting shellfish and whether they were using traditional wooden goggles. He said that only a few still do. Many younger women now try to avoid the sun altogether, seek modern lifestyles, and prefer to stay indoors. Apart from Lohoa, it is only in Sampela where women still commonly collect shellfish—though even there, a clear generational gap is emerging.

When I asked Pondang about the relaxed atmosphere, and about why so many men were shirtless in Lohoa, he suggested it was because they had recently returned from fishing. I suspect it reflects something more habitual—a different rhythm of everyday life. Lohoa felt smaller, cleaner, and calmer, and children moved through the water with ease, diving, swimming, and playing effortlessly.

Reading Wengki Ariando’s Stringing the Islands later confirmed many of my impressions. In the book, he briefly describes Sama Bajau communities across Wakatobi, and Lohoa fits the picture well: only a few people have completed high school, and women and children are deeply involved in making a living from the sea. It is a more traditional community, founded by families from Sampela in the 1970s.

Some Sama Bajau elsewhere in Wakatobi view Lohoa as backward—odd in behavior, speech, or clothing. Yet the sense of joy and calm I felt there was difficult not to be affected by.

Resilience at the Edge of the Sea

When we left Sampela a few days later, at six in the morning, we saw Kabei leading three small boats tied together, moving slowly across the water. Women sat aboard, steering each canoe toward a day of foraging in the shallows. As we passed, Kabei greeted us with a smile, clearly pleased to be heading out to sea.

In many ways, the Sama Bajau are masters of resilience. They cooperate, share, and make use of every available resource. They fish both day and night, read environmental cues, follow the tides, reuse materials, and see what others might call waste as opportunity—the list goes on.

For generations, the Sama Bajau have believed that the sea’s resources are endless—that the ocean will always provide. This worldview may seem naïve from a Western perspective, but it has worked for centuries, offering a sense of security rooted not in savings or property, but in trust in the natural world.

In contrast, we in the West tend to seek security through bank accounts, investments, and future returns. For the Sama Bajau, security has long been something lived and practiced daily, not something abstract and stored away.

As I watched Kabei lead the small flotilla across the water—four boats pulled by a single small engine—I was moved. He is holding on to a traditional way of life, having to add resilience day by day, as that way of life alone is no longer enough in the face of mounting environmental and social pressure.

The corals are slowly dying, yet he believes they will endure.

For him, it is almost impossible to think otherwise.

This belief is not denial, but a way of being—something lived and embodied from childhood.

Diving, moving, and living in the sea offer not only sustenance, but meaning.

And, perhaps, a sense of transcendence.

Exploring the Lives of the Sama Bajau: A Field Report from Sabah, Malaysia

Amidst the bustling activity of the Philippine night market in Kota Kinabalu, I found myself surrounded by the vibrant energy of fish vendors, children selling plastic bags, men and women in worn-out clothes transporting ice on wheelbarrows, and restaurant owners showcasing mantis shrimp and lobster in front of warm grills. This market, a microcosm of the larger economic struggles faced by the Sama Dilaut, became the starting point of my field trip to Sabah, Malaysia, aimed at collecting data for my thesis on the Sama Dilaut’s role in the economy and fishing industry.

At the turn of the year from 2022 to 2023, I embarked on this journey to delve into the lives and challenges of the Sama. Despite their hard work and exceptional fishing skills, they continually struggle with capital and opportunities, often finding themselves on the losing end of trade. To better understand their plight, I employed the “follow the thing” methodology, as elaborated by Appadurai, focusing on the seafood chain. Fish serve as a lens through which we can explore critical issues such as conservation, destructive fishing methods, and structural violence.

Kota Kinabalu: A Vibrant Market Scene

The trip began in Kota Kinabalu, the largest city and tourist hub in northern Sabah. This city hosts a bustling Philippine night market with various Sama Bajau groups from numerous Philippine Islands. The harbor, filled with trawlers, longliners, and shrimp boats, serves as a transit hub for fish trade. Across the water lies Pulau Gaya, home to many undocumented migrants from the Philippines. I engaged with local fish vendors, small seafood restaurant owners, Sama Dilaut children selling plastic bags, fish traders, boatmen, and more. As always, crowds gathered around me when they realized that I speak Sinama, often filming to boost their social media following. Common questions included how long I had been learning Sinama, if I could speak Malay or Tausug, if I was married and how much dowry is in my country.

One afternoon, I decided to visit Pondo on Pulau Gaya, which is designated a ‘no-go zone.’ At the informal jetty, I befriended a young Filipino man who helped me cross to Pondo, after carefully evading the Marine Police that controlled the area. We docked at Ridwan’s parents’ stilt house and walked towards the island, surrounded by excitement and friendly questions. A group of children followed us, asking for candy, which I promised to give later to avoid too much fuss. However, due to serious problems with drugs and glue-sniffing, it was unsuitable to stay long. After 30 minutes, we returned to the boat, bought candies for the kids, and headed back to the city.

Upon arrival, I found myself amidst a volleyball match between fish traders, who saw me arriving from the sea, leading to a relaxed atmosphere filled with questions and jokes.

Meetings with Stakeholders in Kota Kinabalu

In Kota Kinabalu, I met Terrence Lim, the director of Stop Fish Bombing Malaysia, an organization dedicated to combating destructive fishing methods. He shared insights into fish bombing, cyanide fishing, and the marginalization of the Sama Dilaut community. According to Terrence, “Fish trades can now be settled at sea. Everyone has a phone, and money is being sent online.” However, he explained that the Sama Dilaut cannot register SIM cards and are completely dependent on the informal cash-driven economy.

Terrence also mentioned, “Big fishing boats are using sonars for fishing, and there’s a growing concern about the difficulty of catching big fish, further marginalizing the Sama Dilaut community.” He further explained that the Sama Bajau are often on the losing end of negotiations, having to sell their fish quickly due to lack of storage and their statelessness.

Kudat: Exploring New Horizons

Next, I traveled to Kudat, located in the northernmost part of Sabah. The Tun Mustafa Marine Park is here, though it attracts fewer tourists compared to other popular destinations. My goal was to explore new areas where many Sama Dilaut from Semporna had moved in search of better opportunities. After purchasing ferry tickets—and taking photos with the young female vendors who recognized me from social media posts in Kota Kinabalu—I met the chief engineer, who shared insights about the area’s environmental issues, including pollution and acidification. Upon arrival, I realized that most residents were Ubian, a Sama group from an island near Tawi-Tawi in the Philippines.

I looked for someone to take me to Bankawan Island, east of Banggi, where Terrence had mentioned a recently established Sama Dilaut community. I met a group of older men who helped me find a boatman. Next morning, we drove towards a cluster of three anchored houseboats, and the people on them greeted us warmly with big smiles. One young father, holding his baby boy with a protective amulet around his neck and arm, pointed at me and said “melikan, melikan” while waving happily.

The meeting was full of contrasts. The father continued to socialize with his little child, who had likely seen a white person for the first time. This made it a special occasion for the Sama Dilaut, who generally hold white people in high regard, having had mostly positive experiences with them in the past. We talked about their fishing habits and how long they had been living in the area. The father on the boat said they had been there for a few years and showed me some shellfish and a lobster they were planning to sell in Karaket. A young boy wearing a Neymar Jr. t-shirt was fishing with a hook and line, while a young man standing on the roof of the larger houseboat asked for my phone number, holding up a mobile phone. They told me fishing was better in Kudat than in Semporna and that they didn’t plan to return to Semporna.

Before leaving, I offered cookies and money. We also spoke to other houseboats, learning about nearby Sama Dilaut communities around the Tun Mustafa Marine Park. We were invited to a water village, clearly visible on Google Earth, where we toured and saw sea cucumbers being farmed. The community consisted largely of undocumented migrants from the Philippines, making their living from fishing and fish farming.

Semporna: A Deep Dive into Local Life

The final destination was Semporna, where I have spent significant time during previous trips to Sabah. Over the years, I have established relationships with various people and places in Semporna, allowing me to gather valuable information. The central market, which had faced years of construction delays due to lack of funds and alleged corruption, was finally completed. However, it was mostly abandoned, with only the fruit and fish markets being utilized. The rest of the trade took place on small tables scattered around sidewalks and walkways, particularly in Kampung Air. Young boys had turned the new central market into a makeshift football field, giving the area an almost ghost-town feel.

Walking through Kampung Air, I noticed the bustling activity with small restaurants, cafes, and stalls selling various goods. The Sama Dilaut who had come to buy staples and sell fish were as always very silent, reflecting the everyday struggles they face, such as racism, poverty, statelessness, and difficulties in making a living at sea. All these challenges can be described as structural violence, a concept originally put forward by sociologist Johan Galtung. This violence has no clear beginning or end, and no single person to blame. It is embedded in the spaces in between—in the market, in the tone of the seller, in the waiting room at the health clinic, and in the long gazes on the street.This was later reflected when I stumbled across a few fishermen from Bangau Bangau who had brought in a sizable catch of cuttlefish. When I asked them how many days they had been out at sea, they replied, “Three days,” at which point the fish trader, who had just started to weigh their catch, said with disdain in his voice, “Sleeping, eating, and pooping on the boat,” whereupon the Sama men fell silent once again.

Further down the wooden bridges, I noticed dried moray eels being prepared for sale. A vendor explained that these eels are bought from fishermen for 5 RM (approximately $1.10 USD) per kilo, dried, and then sold for 15 RM (approximately $3.30 USD) per kilo in Tawau. This 200% increase in value highlights the inadequate compensation the Sama Dilaut receive for their livelihood.

At a nearby store selling fishing equipment, I observed items reflecting various fishing methods used in the area—spear gun fishing, hook and line fishing, net fishing, and compressor diving. The new fish market near Kampung Air was lively, with many people recognizing me from previous visits. The market offered a wide variety of fish, and I engaged with children selling plastic bags, who were amazed that I could speak Sinama.

Exploring Sama Villages and Marine Life with Sabah Parks

Following Sabah Parks on one of their tours, I visited the Sama Dilaut village of Tatagan, located at the foot of Mount Bod Gaya in the Tun Sakaran Marine Park. Despite tensions between Sabah Parks and the village, I met Kirihati, one of the few who still live on larger houseboats. He shared his experiences and the challenges of maintaining this traditional way of life. Kirihati was growing medicinal plants on the roof of his houseboat, and on land, he was in the process of building a new houseboat with the help of a skilled boat builder.

Later, we visited Bohey Dulang, where Sabah Parks had an exhibition about marine life, including an albino turtle—a rare and fascinating sight. The caretaker was thrilled to show us this unique addition to their collection, explaining that albino turtles are extremely rare.

The final stop was the paradise island of Sibuan, home to a small group of Sama Dilaut, Malaysian soldiers, and Sabah Park rangers. On Sibuan, we stumbled upon a Photo Safari session. Two overly talkative and enthusiastic interpreters, who were themselves Sama Bajau, urged all the Sama Dilaut children to line up. A group of tourists from the Malaysian mainland then handed out snacks to the children. Afterwards, mandatory photography ensued, and I was invited to participate.

Following Terence on a Busy Work Day

While in Semporna, I joined Terence, who had come down from Kota Kinabalu, on a day trip to check on his bomb-detecting sensors scattered throughout the area. Stop Fish Bombing Malaysia has over 10 sensors covering a large part of the sea. Terence explained that the number of explosions had dramatically decreased, especially near Bum Bum Island. However, some sensors had been bombed by fishermen who opposed the initiative. We also checked on a radar installed on Sanlakan Island, which helps track boats involved in fish bombing.

Visit to Bangau Bangau

One day, I visited Bangau Bangau, home to many Sama Dilaut who arrived from Sitangkai in the Philippines in the 1960s. Most villagers now have Malaysian Identity Cards, but many who came later remain undocumented. Some of the residents have become middlemen in the fishing trade or taken on regular jobs, with their cars parked next to the water bridges, while others continue as traditional fishermen.

I reconnected with an old friend, Si Wanti, a former boat driver who had taken me out to sea many times in the past. Now, he makes a living from small-scale net fishing. I gave him shark and coral fish posters in Sinama, which fascinated many of the elders. An old man living in the same compound as Wanti was particularly happy to see the shark poster. When I read out the names of the sharks to him, he was amazed that I even knew their names. He looked at the collage for a long time, identifying the sharks one after another. He was impressed that all the sharks had been put together in one photo and remarked that the person who took the photos must be very brave.

Reflections and Key Takeaways

Throughout my trip, I learned more about the fish value chain. For instance, moray eels are bought for 5 RM per kilo and sold for 15 RM per kilo in Tawau, representing a 200% increase in value. It’s clear that the Sama Dilaut are not adequately compensated for their hard work. They dive and fish under harsh conditions, only to sell their catch for a pittance, benefiting middlemen and end consumers who enjoy seafood at low prices. Industrial fishing forces down prices, leaving subsistence fishermen and the environment to pay the ultimate price.

People are constantly pushed to their limits, driven by physical needs and market forces. While only those higher up the value chain may become wealthy, the majority must keep pushing themselves and their environment daily. Despite the hardships, the Sama Dilaut have a deep fascination and love for the sea. They cherish moments of peace with their loved ones, swaying with the waves and watching the sunset after a fulfilling meal. However, their constant struggle for survival amidst harsh conditions places them in the grip of structural violence.

Fish serve as a lens through which we can explore important issues such as conservation, destructive fishing methods, and the structural violence faced by the Sama Dilaut. Despite their hard work and fishing skills, the Sama Dilaut continually struggle with capital and opportunities, often losing out in the economic trade. Most Sama Dilaut today live near marine national parks like Tun Sakaran Marine Park in Semporna and Tun Mustafa Marine Park in Kudat. These areas prohibit large-scale fishing, creating a niche for Sama Dilaut and other groups.

However, competition is intense, and resources are limited. Coral bleaching is already a concerning development in the area, threatening the delicate marine ecosystems that the Sama Dilaut depend on for their livelihood. Their resilience and deep connection to the sea highlight the need for greater support and sustainable practices to preserve their way of life and the marine environment they depend on. Ensuring the sustainability of these ecosystems is crucial not only for the Sama Dilaut but for the broader health of our oceans.

The resilience and deep connection to the sea exhibited by the Sama Dilaut, despite the immense challenges they face, underscore the urgent need for greater support and sustainable practices. By preserving their way of life and the delicate marine environment they depend on, we not only honor their rich cultural heritage but also safeguard the health of our oceans for future generations. Their story is a powerful reminder of the intricate bond between humans and nature, and the critical importance of fostering both community and environmental sustainability.