The Machine-Human and the Myth of Superintelligence

We live in an age where AI is celebrated as humanity’s next great leap – the path to artificial general intelligence (AGI), superintelligence and a society that automates everything. But behind the hype lies another story: our creativity is bodily, born of crises and lived experiences, and cannot be programmed. At the same time, we risk becoming increasingly machine-like ourselves, as technology shapes how we see the world and ourselves. The most radical innovation of the future is therefore not a supercomputer – but a human being who refuses to become a machine.

Artificial intelligence dominates today’s technological discourse. Many predict that machines will soon match or surpass our own intelligence, which would render human intelligence obsolete. Billions have been poured into this dream, and the brightest minds are given time and resources to open Pandora’s box.

Proponents of this view, such as Nick Bostrom, argue that because intelligence rests on physical substrates – like the human brain – there is no reason it could not be recreated on a much larger scale, unbound by the confines of the human skull (Bostrom, 2014).

But is this really possible – or are we just building castles in the air?

The Theory of Cyclical Development Undermines the AI Hype

According to the theory of cyclical development – which I have previously presented on this blog – human intelligence and creativity go beyond algorithms. They are part of life itself, deeply rooted in existential experiences and crises, and they are non-deterministic.

Early Homo sapiens learned survival through imitation within a rhythmic song system that maintained extremely durable lifeways over hundreds of thousands of years. Mirror-neuron networks made it possible to accurately imitate toolmaking and movement patterns across generations. During evolution the brain did not grow because we became ever more creative; it grew because we became better at reproducing and consolidating survival strategies that already worked.

The original function of language was therefore, in the form of song and rhythm, to guide people in their daily tasks – to synchronise thought and body, individual and environment – rather than to constantly invent new things. The free, infinite language, the abstract speech we now take for granted, arose much later. Only about 75,000 years ago did the vocal song system shift to a fully symbolic language, unleashing not only new ways of thinking and communicating but also new ways of moving.

When sudden environmental changes made old routines impossible – for example ice-age pulses and above all the Toba super-eruption – the song system “overheated”. Song ran idle, cognitive dissonance arose, experimentation exploded and new tools, art forms and social systems were born.

Language was an invention of innovative people in a tumultuous time – and this applies to all our ancestors in the genus Homo who went through the same cyclical process. Even Homo erectus and Homo heidelbergensis experienced crises and invented new survival strategies, then let the brain and the song cement the new solutions and lifeways, whereupon the brain grew larger again.

This represents a Copernican revolution in how we view human evolution – we flip the coin: larger brains did not evolve to make us ever more ingenious, but to effectively reproduce acquired survival strategies and close the gap between body and thought, human and habitat – through song and mirror neurons. Creativity continued to develop but as a latent reserve beneath the solid surface – ready to break through when the next crisis tore down imitation’s hegemony.

This means that genuine creativity and innovation are deeply rooted in the human body: in emotions, sensory impressions and physical interaction with the world. They arise out of cognitive dissonance – the tension between expectation and experience, between body and soul – and they are not deterministic. They emerge from chaos and are truly free and transformative.

Machines, by contrast, lack frustration, wonder and joy. They manipulate symbols but have no conscious relationship to them.

Human intelligence thus did not emerge through a gradual, deterministic natural selection where generation after generation became ever smarter in response to a changing environment. It arose latently – and when it finally burst forth it was untamed and went beyond the programmable, as part of life’s very lifeblood. This cannot be recreated in a laboratory – no more than we can create life itself.

Large Language Models and Their Limitations

Our largest language models operate strictly within a logical, stripped-down system of propositions. There is hardly any genuine creativity there – only rapid, massive recombination of already existing texts. This stands in sharp contrast to how actual scientific and intellectual breakthroughs occur.

Alfred Russel Wallace had his evolutionary insight while feverish in Indonesia – the idea of natural selection struck like a revelation, not as the result of formal deduction. Albert Einstein described “the happiest thought of my life” when, working at the patent office in Bern, he imagined an observer in free fall – a sudden flash of insight that later led to the general theory of relativity and fundamentally changed our worldview.

Such non-logical breakthroughs lie completely beyond today’s LLM architecture. Today’s AI – even the most sophisticated models – engage in algorithmic manipulation of symbols without lifeblood. They lack the existential creativity that only appears when imitation’s chains break, when body and thought collide and free language arises. AGI presupposes a “brain in a box” that can evolve without a physical, existential embodiment. All of this AI lacks.

The Machine-Human – The Real Danger

Ironically, it is not technology that is becoming more human today, but humans who risk becoming more machine-like. Philosopher Martin Heidegger spoke of technology’s ability to “unconceal” reality – to make us see the world in a new way. In the new computerised era we are reduced to data points, patterns and functions that can be optimised. When the world is revealed through the grid of technology we begin to see ourselves as resources, as machinery.

This has two crucial consequences:

- Loss of human dignity. If humans are seen as just another algorithm, the foundation of our inviolability dissolves. People become interchangeable, measurable and comparable in the same logic as raw materials and means of production. We are seen as programmable automatons – a view that threatens to dehumanise us and in the long run erode human rights. If we start to see people as fallible machines rather than moral subjects, we open the door to a society where the value of each person can be measured, priced and – in the worst case – switched off.

- Humans become technology. In our drive for efficiency and optimisation we ourselves become increasingly machine-like. We live by measurable rules, let algorithms guide our decisions and make ourselves ever more bound by laws. It is not technology that becomes human – it is we who become technology.

Heidegger would say that this is the real danger: not technology itself, but that we see the world – and ourselves – only through the grid of technology. We then forget other ways of being human, other ways of living and understanding ourselves.

Heidegger’s allegory of everyday language and poetry offers a powerful tool for understanding this danger. He did not mean that poetry arose from everyday language as its highest form, but rather the opposite – that the original language was poetic, open and full of wonder. The first modern humans were thus grand poets (Heidegger, 1971). It is this poetry, this spiritual and non-physical dimension, that is now being lost in the AI era.

AI Is Like Any Other Technology

AI is fundamentally like any other technology. It is not exceptional; it cannot create by itself but only in interaction with humans – just like writing, the wheel and other groundbreaking innovations.

But the danger is that AI risks reinforcing an already ongoing, dehumanising process – a process that capital accumulation in symbiosis with technology has long driven. Technology shifts boundaries and stretches its tentacles deep into the periphery to suck resources into the centre, just as human ecologist Alf Hornborg has shown (Hornborg, 2022). In the centre, people become intoxicated by the illusion of freedom and dream of eternal life. But in practice we feed the machines – not the humans – something the gigantic, extremely energy-hungry data centres demonstrate with brutal clarity.

Reclaim the Human

Even though we will never achieve either artificial general intelligence or superintelligence – something that will likely soon burst the AI bubble with enormous economic consequences – AI will still become an ever larger part of the infrastructure that feeds injustice and alienation. Economic power will concentrate into even fewer hands, and at the same time we risk changing ourselves: becoming ever more standardised, ever more governed by the logic of algorithms, ever more entangled with technology – and ever less poetic.

The most radical innovation of the future is therefore not a supercomputer – but a human being who refuses to become a machine.

References

Bostrom, N. (2014). Superintelligence: Paths, Dangers, Strategies. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Heidegger, M. (1971). Poetry, Language, Thought. Trans. A. Hofstadter. New York: Harper & Row. (Includes the lecture “…dichterisch wohnet der Mensch…” delivered 1951.)

Hornborg, A. (2022). The Magic of Technology: The Machine as a Transformation of Slavery. London & New York: Routledge.

Tracing Ancient Shorelines: Field Notes from Java on Early Human Evolution

In mid-February, I returned to Southeast Asia—this time to Indonesia—together with Professor Erika Schagatay. At the start of our trip, we met up with Professor José Joordens, a Dutch anthropologist and paleoanthropologist. With her, we visited several excavation sites where she has been working, as well as museums in central Java.

José Joordens became widely known for her work on the engraved freshwater Pseudodon shell from Trinil—a remarkable artifact originally collected by Eugène Dubois and his team in the 1890s and later kept in Dutch museums.

The zig-zag engraving on one of these shells went unnoticed for more than a century. It was in fact archaeologist Stephen Munro who recognized the engraving already in 2007, while examining photographs he had taken of the shell collection in Naturalis Biodiversity Center. The finding was later formally described in 2014. The carving has been dated to between approximately 430,000 and 540,000 years ago, making it the oldest known example of an abstract or symbolic marking created by any human.

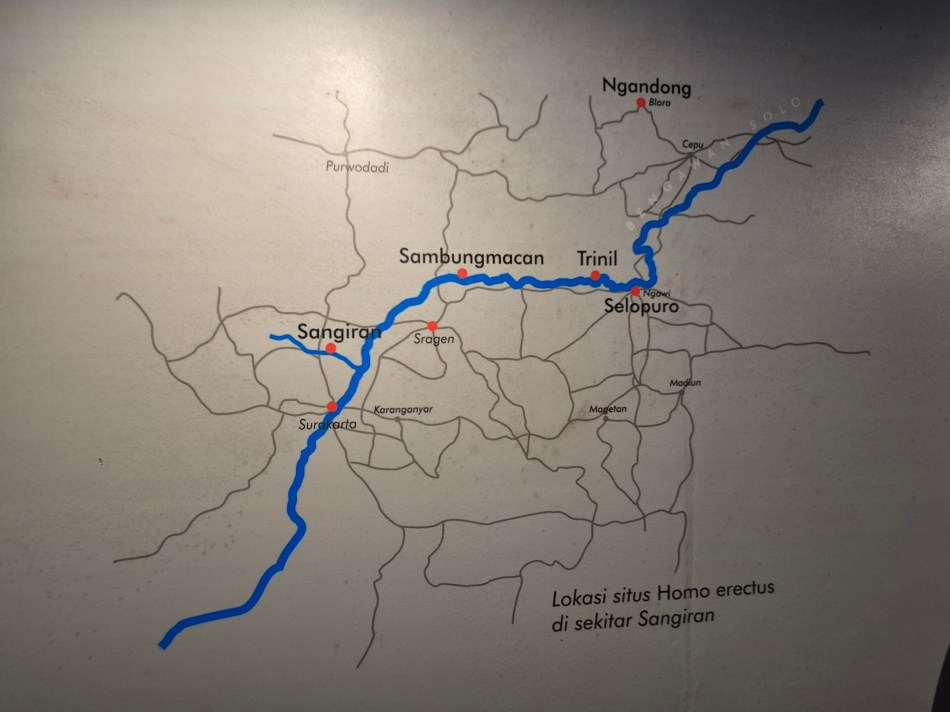

Along the Solo River and the World of Homo erectus

The Solo River basin is one of the richest regions in the world for Homo erectus discoveries. Groups of H. erectus lived along this river system from roughly 2 million years ago until as recently as 100,000 years ago, including the well-known Ngandong population—among the latest surviving Homo erectus known.

During our trip, Erika and José also met with numerous local researchers as part of early planning for a future interdisciplinary project on the Bajau Laut (Sama-Bajau) communities. The project aims to explore diving adaptations from physiological, anthropological, and cultural perspectives.

José has a long-standing interest in the waterside hypothesis and suggests that Homo erectus may have been shallow-water divers and foragers. The argument is supported by evidence such as thick cortical bones, a relatively dense skeleton, potential breath-hold capacity, and repeated associations with shell-bearing or riverine sites. The Trinil shell assemblage is central here, and it has also shown that shells were used as tools. In addition, José has excavated in Kenya’s Turkana Basin—another key region for early hominin interactions with aquatic environments.

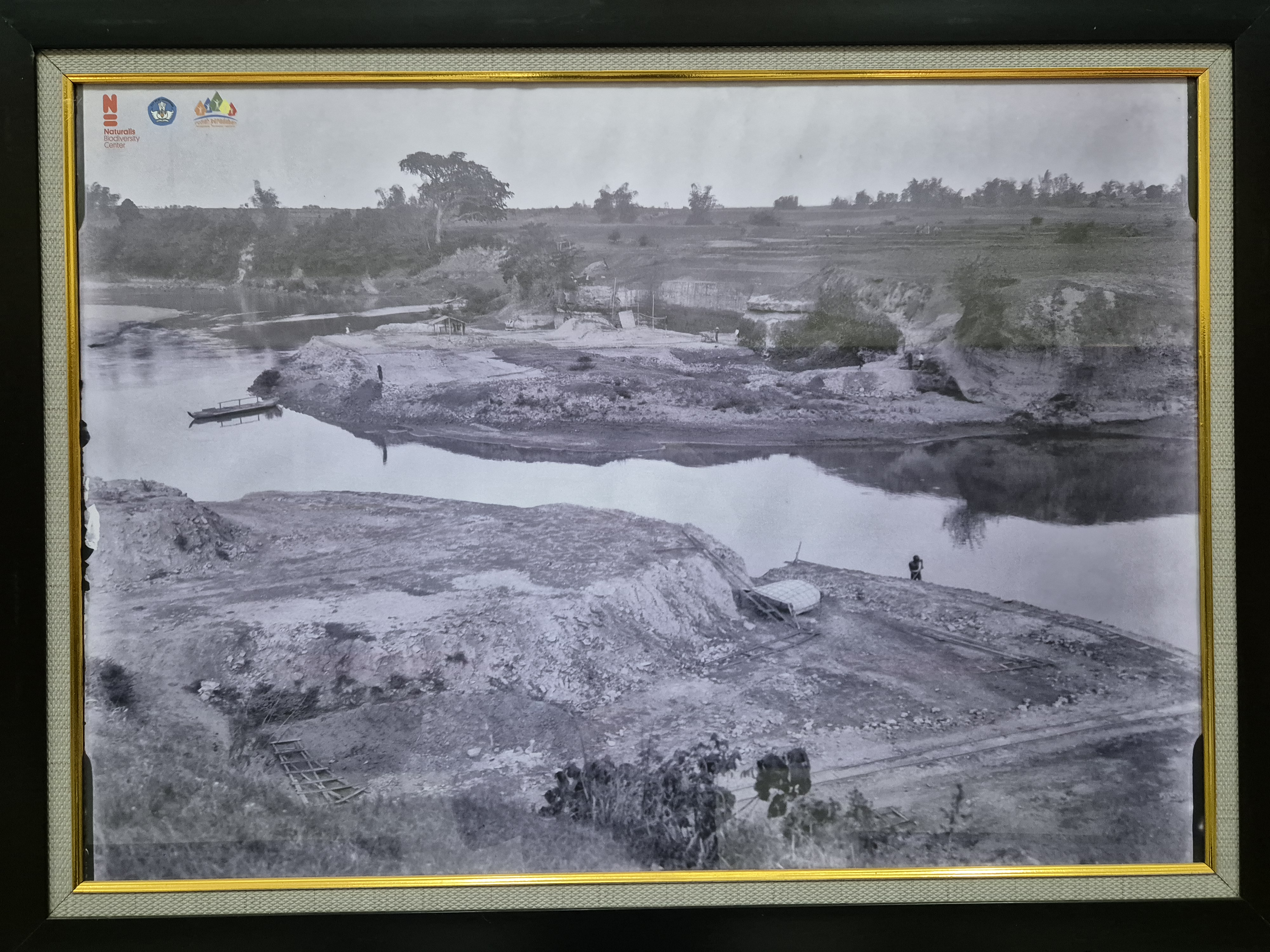

Visiting Trinil: Dubois’s Historic Site

One of the highlights of our journey was visiting Trinil, where Eugène Dubois uncovered the first Homo erectus fossils—his famous “Java Man.” It was also here that the engraved shell was found. Local people still consider the site haunted, and many avoid being there at night. During Dubois’s excavations, prisoners were used as laborers, and a number of them died during the work, reportedly chained together and forced to excavate under horrific conditions.

We met long-time collaborators of José who have worked at Trinil for years. We also had access to a back room where numerous remnants, casts, and planning materials are kept, including a copy of the engraved Pseudodon shell. In the surrounding area, we also explored exhibitions and museums that highlight the life and environment of Homo erectus. Standing by the Solo River—where the earliest discoveries of Java Man were made, alongside men fishing with large handheld nets—brought a quiet sense of continuity between past and present.

A Waterside Landscape Two Million Years Ago

Java was a very different place two million years ago. The region was shaped by extensive river systems, lakes, wetlands, and coastal environments, and supported a wide range of mammals adapted to aquatic or semi-aquatic niches—such as hippos, elephants, and other water-associated species. Humans were part of this landscape, and this is also the region where Homo erectus appears to have persisted the longest.

Fossils attributed to Homo erectus appear in Africa at around two million years ago, including recent finds from sites such as Drimolen in South Africa, while the well-known Dmanisi material in Georgia dates to around 1.8 million years ago. In Southeast Asia, the Java record begins around 1.8 million years ago and continues until approximately 100,000 years ago.

Over this immense timespan, H. erectus brains increased in size—a gradual but significant development that may reflect changing environments and a long-term reliance on nutrient-rich aquatic and waterside resources.

In other parts of the world, Homo erectus either evolved into other lineages (for example through Homo heidelbergensis, often discussed as a common ancestor of Homo sapiens, Neanderthals, and Denisovans) or went extinct. Yet on isolated islands in Southeast Asia—such as Flores, Luzon, and Sulawesi—human species appear to have persisted much longer.

Water, Diving, and Human Evolution

Homo erectus had characteristically thick bones and may have been skilled divers. According to some researchers—especially Marc Verhaegen—the species’ history of breath-hold diving shaped both biology and behavior. Verhaegen argues that:

- Homo erectus frequently exploited coastal, riverine, and lake environments.

- Breath-hold diving may have been used to collect shellfish, aquatic plants, and other high-value foods.

- Their relatively heavy and dense skeleton may have functioned as natural ballast during shallow diving.

- In addition to diving, Homo erectus may often have floated on the back while foraging at the surface—somewhat comparable to modern sea otters—allowing extended time in the water with minimal energy expenditure.

- Long-term reliance on aquatic resources could have influenced brain growth and broader physiology.

- Cranial features such as paranasal air sinuses have been discussed in relation to pressure regulation and repeated submersion, though interpretations remain debated.

- Other traits sometimes highlighted include the ability to suck shellfish from shells and hypersensitive fingertips, well suited for detecting hidden prey while foraging underwater.

Homo sapiens later continued to exploit marine foods, which is significant given our need for DHA fatty acids to support a large brain. Although our species eventually became less dependent on diving, technological development likely allowed us to harvest aquatic resources in new and more efficient ways. Coastal foraging probably remained crucial even as our bodies became lighter and more specialized for long-distance walking and endurance running.

Average brain size in the human lineage increased steadily until roughly 300,000–200,000 years ago, after which it appears to have plateaued. A gradual reduction in average brain size becomes visible later, beginning around 50,000 years ago and continuing into more recent prehistory.

Given the high energetic demands of large brains, it seems likely that nutrient-rich foods centered on marine and aquatic resources played an important role during the period of brain expansion. The later reduction in brain size may reflect a gradual decrease in reliance on these resources as humans increasingly diversified their diets and food sources. Many large-brained mammals are closely tied to aquatic food chains during their evolution, which helps explain why the relationship between water, diet, and brain evolution remains such an intriguing topic.

Interestingly, some of the museums we visited—such as the Sangiran Museum Site—explicitly embraced the idea that Homo erectus lived close to water and may represent the earliest island-adapted human. Seeing this interpretation presented so openly was refreshing.

Engraved Shells and Shared Human Cognition

The Trinil shell itself is fascinating. Its zig-zag pattern resembles markings found in other early human contexts, such as the cross-hatched engravings made by early Homo sapiens on pieces of red ochre at Blombos Cave in South Africa (dated to about 73,000 years ago), as well as early Neanderthal engravings, including the cross-hatched markings from Gorham’s Cave in Gibraltar (~39,000 years old).

These similarities raise intriguing possibilities about shared cognitive tendencies—suggesting that geometric pattern-making may reflect deep underlying structures of human and pre-human thought. It also points to a long period when abstract marks existed without figurative art, before a later shift within Homo sapiens—after our species had already been around for more than 200,000 years.

Final Reflections

Traveling with José was inspiring. She is one of the few paleoanthropologists who treats the waterside hypothesis with genuine scientific curiosity, and her background as a marine biologist adds depth to her perspectives.

It is also striking that the earliest known sign of abstract behavior—an intentional engraving—comes not from stone tools or cave walls, but from a freshwater shell, further highlighting the importance of waterside environments in our evolutionary history.

The Paradigm Shaping Our Understanding of Human Evolution

Our understanding of human evolution is not just a scientific endeavor but also a reflection of our self-perception and cultural preconceptions. These elements form part of the underlying paradigm—as discussed by Thomas Kuhn (1962)—or “doxa,” a concept similar to a paradigm introduced by philosopher Pierre Bourdieu (1977), that shapes our understanding of ourselves.

In this context, the theory of evolution, while groundbreaking, has not fundamentally altered our societal structures or self-conception. Instead, it has been adapted to reinforce the cultural and intellectual frameworks that have influenced Western thought for over two millennia, starting from the birth of philosophy.

In our modern, fast-paced culture, we have lost touch with the concept of stability in nature and society. We struggle to imagine a world where multiple generations coexist within the same deep-rooted reality. Our ancestors did not need to be perpetually inventive; rather, their lifestyles were remarkably stable—a fact evidenced by traditional hunter-gatherer societies like the !Kung people (Lee, 1979) and Australian Aboriginals (Tonkinson, 1978). The worldview of these traditional peoples was cyclical rather than linear (Eliade, 1954). In many traditional cultures, humans were regarded as immature and subordinate beings—apprentices to nature, the ultimate teacher (Ingold, 2000). However, over time, this worldview has shifted from being cyclical and holistic to linear, obsessed with the idea of progress and liberation from our natural limitations (Nisbet, 1980).

In previous blog posts, I have discussed the prevailing paradigm in anthropology that emphasizes human intelligence and flexibility, which can make it challenging to consider alternative theories like the aquatic ape theory. In this blog post, we will take a closer look at the deeper perceptions behind the current paradigm of flexible man.

Characteristics of Our Current Paradigm

Our current paradigm is closely intertwined with our views on economic growth and the valorization of entrepreneurship. We project our beliefs about ourselves onto our understanding of evolution, turning it into a form of storytelling. This narrative began with “Man the Hunter” (Lee & DeVore, 1968) and evolved into the “Savannah Hypothesis,” which, after being challenged, transformed into the concept of a mosaic of environments requiring constant flexibility (Potts, 1998). Human intelligence is seen as a trait akin to a lion’s strength or a cheetah’s speed. While animals became faster, more agile, and stronger, humans became smarter. Philosopher Karl Popper summarized this perspective well with his quote: “Our theories die in our place” (Popper, 1963, p. 216).

This paradigm is characterized by deep-seated feelings and assumptions, fundamentally unchanged over centuries—as elaborated by Thomas Kuhn in his concept of paradigms (Kuhn, 1962) and referred to as “doxa” by Bourdieu (1977). This enduring paradigm is not only evident in academic theories but also permeates our literature and cultural narratives. In literature, this perspective is vividly illustrated in Robinson Crusoe (Defoe, 1719), widely regarded as the first modern novel. Stranded alone on a remote island, Crusoe methodically tackles each challenge with resilience and ingenuity, viewing nature as a resource to be mastered. His journey reflects the Enlightenment-era view of man in his authentic state—capable of adapting, solving problems, and exercising rationality to shape his environment (McInelly, 2003). When he meets Friday, Crusoe regards him as a noble savage whom he begins to teach civilized behavior. Eventually, Friday refers to Crusoe as “Master.”

In anthropology, one of the central questions has often been why humans began walking on two legs. This shift to bipedalism was seen as a pivotal development that freed our hands for tool use and allowed for greater flexibility in our behavior (Darwin, 1871). Consequently, much of human evolution has been attributed to our own ingenuity and adaptability, enabling us to become masters of diverse environments.

However, transitioning from quadrupedalism to bipedalism required significant anatomical transformations, particularly in the structure of the knee and pelvis (Lovejoy, 1988). This raises questions about whether the intermediate stages could have been evolutionarily advantageous. Anthropologist Owen Lovejoy suggested that bipedalism arose to enable males to carry food to females, thereby promoting monogamy (Lovejoy, 1981). Such theories reflect our tendency to view human evolution through the lens of our own cultural values. The idea that males would carry food to a single childbearing female reinforces the ideal of monogamy, projecting contemporary social norms onto our ancestors—even though monogamy is not universal among human societies and is not genetically predetermined.

The Influence of Western Philosophy

The roots of our current paradigm can be traced back to ancient Greece. Thinkers such as Plato and Aristotle laid the foundation for the Western emphasis on reason and intellect. Aristotle’s idea of the “rational animal” positioned humans as unique in their capacity for logical thought (Aristotle, trans. 2000).

René Descartes, with his declaration “Cogito, ergo sum” (“I think, therefore I am”) (Descartes, 1641/1996), reinforced the centrality of human reason. Both Descartes and Aristotle were entrenched in the same paradigm that prioritizes rationality as the core of human identity. There has been a consistent thread in the history of philosophy, placing human intellect at the center and viewing it as the essence of humanity. Another manifestation of this enduring paradigm is seen in modern economics, where the “rational actor” model presumes individuals make decisions purely based on logical self-interest, reinforcing the ideal of human rationality.

The aquatic ape theory challenges this paradigm because it explains many human characteristics that anthropologists have traditionally thought did not require explanation. The theory forces us to recognize that, for most of our evolution, we lived in a semi-aquatic environment and were not the flexible entrepreneurs roaming the African terrestrial lands.

Back to the Roots of Evolutionary Theory

Let’s return to the basics of evolutionary theory. Evolution occurs through natural selection when a particular trait is not just successful in one or two generations but remains advantageous over many generations (Darwin, 1859). For evolution to occur, the same traits must be selected repeatedly, which means there must be continuity in development. Simplistically, evolution moves toward an adaptive peak—an optimal state. In evolutionary biology, the concept of an Evolutionarily Stable Strategy (ESS) suggests that there is a way of life, a particular strategy, that outperforms all others in a stable environment (Maynard Smith, 1982).

From this, we can conclude that as long as evolution is occurring, a species must live in the same way for generation after generation. When significant changes happen rapidly, evolutionary development can stagnate because there isn’t sufficient time for advantageous traits to be consistently selected (Gould & Eldredge, 1977). For example, the transition from Homo heidelbergensis to Homo sapiens involved not only an increased brain volume but also a lighter and more agile body structure, smaller jaws and chewing muscles, less robust bones, and more (Rightmire 2008), which is a clear indication that during this time, humans repeated the same living patterns generation after generation.

Human intelligence could not, as Alfred Russel Wallace argued, have arisen solely through traditional evolutionary processes focused on immediate survival advantages (Wallace, 1870). A highly specialized body and a flexible and creative brain do not typically emerge simultaneously under standard evolutionary models; these phenomena seem to exclude each other. The emergence of constantly activated creativity would require a prolonged period of environmental instability—a “continuity of chaos”—but nature rarely presents such conditions over extended timescales. Since our physical form has also undergone significant changes, human intelligence and language must have had original functions beyond mere survival adaptability. During evolution, we were, whether we like it or not, more animal-like.

Challenging the Paradigm

In essence, our understanding of human evolution remains a projection of our cultural self-image, shaped by enduring paradigms that elevate human reason and ingenuity. While a few philosophers like Martin Heidegger and Ludwig Wittgenstein have attempted to push humanity off its self-appointed pedestal, their insights have yet to permeate mainstream thought. Heidegger contended that Western philosophy over the past 2,500 years has gone astray, forgetting the fundamental question of being (Heidegger, 1927/1962). Wittgenstein argued that philosophical problems arise because we become entangled in our own rational language and that we must return to language in its everyday, original form to free ourselves from these confusions (Wittgenstein, 1953).

The new theory of human evolution that I have proposed is based on the idea that evolution has led to increased stability and the reproduction of behavior, making us more animal-like—with creative ability emerging latently as the other side of the coin. This theory correctly aligns with the principles of evolution and goes hand in hand with a more grounded, less anthropocentric view of our place in the natural world.

While physics has profoundly transformed our understanding of the universe—forcing us to accept theories that defy everyday intuition, such as relativity and quantum mechanics, which bear similarities to Zen Buddhism (Capra, 1975)—anthropology has not faced a similar upheaval. The theory of evolution, though it shook religious institutions, did not dramatically alter the narrative. It simply replaced divine creation with natural selection, maintaining the notion of human exceptionalism and behavioral flexibility. The time has come for us to question our long-held assumptions and embrace a paradigm shift that truly reflects the complexities of our evolutionary history.

References

Aristotle. (2000). Nicomachean Ethics (R. Crisp, Trans.). Cambridge University Press. (Original work published ca. 350 B.C.E.)

Bourdieu, P. (1977). Outline of a Theory of Practice (R. Nice, Trans.). Cambridge University Press.

Capra, F. (1975). The Tao of Physics. Shambhala Publications.

Darwin, C. (1859). On the Origin of Species. John Murray.

Darwin, C. (1871). The Descent of Man, and Selection in Relation to Sex. John Murray.

Defoe, D. (1719). Robinson Crusoe. W. Taylor.

Descartes, R. (1996). Meditations on First Philosophy (J. Cottingham, Trans.). Cambridge University Press. (Original work published 1641)

Eliade, M. (1954). The Myth of the Eternal Return: Cosmos and History. Princeton University Press.

Gould, S. J., & Eldredge, N. (1977). Punctuated equilibria: The tempo and mode of evolution reconsidered. Paleobiology, 3(2), 115–151.

Heidegger, M. (1962). Being and Time (J. Macquarrie & E. Robinson, Trans.). Harper & Row. (Original work published 1927)

Ingold, T. (2000). The Perception of the Environment: Essays on Livelihood, Dwelling and Skill. Routledge.

Kuhn, T. S. (1962). The Structure of Scientific Revolutions. University of Chicago Press.

Lee, R. B. (1979). The !Kung San: Men, Women, and Work in a Foraging Society. Cambridge University Press.

Lee, R. B., & DeVore, I. (Eds.). (1968). Man the Hunter. Aldine Publishing.

Lovejoy, C. O. (1981). The origin of man. Science, 211(4480), 341–350.

Lovejoy, C. O. (1988). Evolution of human walking. Scientific American, 259(5), 118–125.

Maynard Smith, J. (1982). Evolution and the Theory of Games. Cambridge University Press.

McInelly, B. C. (2003). Expanding empires, expanding selves: Colonialism, the novel, and Robinson Crusoe. Studies in the Novel, 35(1), 1–21.

Nisbet, R. A. (1980). History of the Idea of Progress. Basic Books.

Popper, K. R. (1963). Conjectures and Refutations: The Growth of Scientific Knowledge. Routledge.

Potts, R. (1998). Variability selection in hominid evolution. Evolutionary Anthropology, 7(3), 81–96.

Rightmire, G. P. (2008). Homo heidelbergensis and Middle Pleistocene hominid evolution in Europe and Africa. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 105(48), 19065–19070.

Tonkinson, R. (1978). The Mardu Aborigines: Living the Dream in Australia’s Desert. Holt, Rinehart and Winston.

Wallace, A. R. (1870). Contributions to the Theory of Natural Selection. Macmillan.

Wittgenstein, L. (1953). Philosophical Investigations (G. E. M. Anscombe, Trans.). Blackwell.

The Rise of Modern Behavior: A Copernican Revolution in Understanding Human Evolution

Have we misunderstood the true essence of human evolution and the role of language in our ancient past? In a new article, I propose a Copernican shift in our understanding of language’s original function and the cognitive revolution that began approximately 75,000 years ago.

Traditional views hold that language evolved primarily as a tool for enhanced communication and complex thought. However, this article suggests that language’s original role was more about replicating behaviors linked with tool use, transferring these behaviors from one generation to the next through singing and rhythm. Initially, language served to reconcile the gap between the human body and its environment, which arose with the advent of the first stone tools, enabling early humans to navigate landscapes for which they were not biologically adapted.

This theory resolves a longstanding paradox since the inception of evolutionary theory: although thinking has an evolutionary past, and Homo sapiens are estimated to be 300,000 years old, humans have not always been ‘modern.’ What if humans are not inherently meant to think and act as they do today? What if evolution promoted aspects other than intellectual capability? Accepting this paradox might mean acknowledging that humans have undergone both a gradual evolutionary process, as Darwin suggested, and a rapid developmental leap, as indicated by archaeological findings—without any genetic change in the brain.

This new theory draws support from a diverse array of disciplines. Archaeological records reveal sporadic bursts of creativity alongside a gradual brain development; meanwhile, studies on mirror neurons offer a neurological basis for mimicry and observational learning, essential for transmitting skills and behaviors across generations. Additionally, theories about our aquatic past propose that water-based environments laid the groundwork for the evolution of vocalization and singing. Insights into how children acquire language—focusing on the roles of intonation and rhythm—mirror the significant role that song played over speech. These interdisciplinary findings suggest that our evolutionary path was not a straightforward march towards greater intellectual capability but rather a complex journey marked by periods of significant conformity punctuated by bursts of creative potential since the first stone tools 2.6 million years ago. This perspective helps explain not only the creative outbursts in South Africa 75,000 years ago but also other instances of early possible symbolic behavior, such as the use of shell beads by early Homo sapiens and Neanderthals.

Moreover, this perspective aligns with various global mythologies that narrate an ancient, harmonious coexistence with nature, disrupted by the cognitive revolution. Could the hauntingly beautiful cave paintings, some of the earliest known forms of human art, be interpreted not just as artistic expressions but as calls for help? These artworks could be seen as profound expressions of a deep-seated longing for reconnection with the natural world we once knew.

You can find the article here: The Rise of Modern Behavior: A Copernican Revolution in Understanding Human Evolution