Hard Evidence of Early Human Seafaring and Women’s Role in Marine Foraging

New and fascinating discoveries provide hard evidence for the Aquatic Ape theory, evidence that was not known when Alister Hardy and Elaine Morgan first advocated for this idea. There is now substantial data proving that early humans undertook long maritime journeys, developed unique physiological adaptations, and lived lives closely tied to water. In this blog post, I will examine some of the compelling evidence that supports a semi-aquatic past for humans. These pieces of evidence meet the stringent criteria set by the anthropological community, which demands archaeological proofs for our evolutionary history, rather than merely examining our own bodily adaptations.

Long Early Maritime Journeys

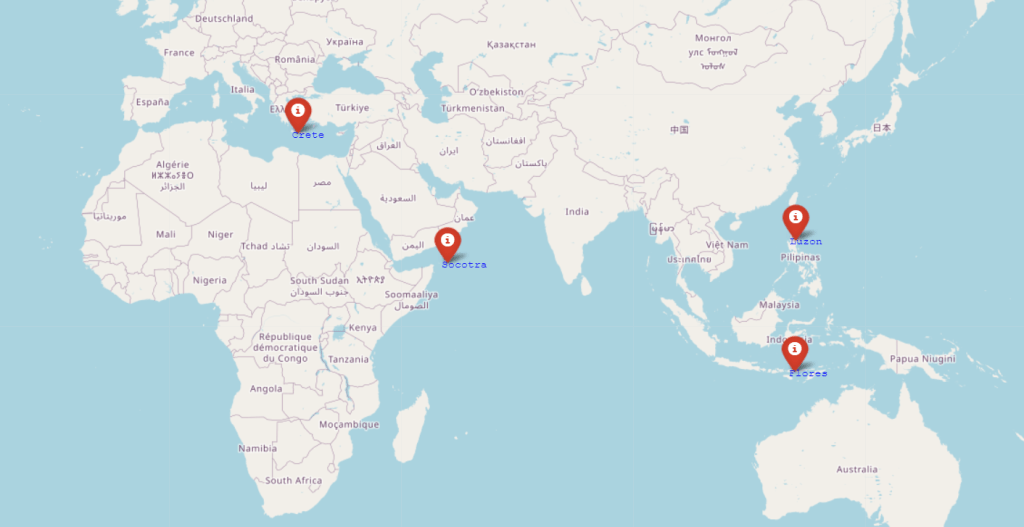

Early human species undertook impressive sea voyages, as evidenced by discoveries of human fossils and stone tools on distant islands that have been separated from the mainland for millions of years. For instance, Homo sapiens reached Australia about 65,000 years ago, a journey that required crossing at least 70-100 km of open sea from Indonesia, traversing the significant biogeographical barrier known as Wallace Line (O’Connell, Allen, & Hawkes, 2010). Similarly, Homo heidelbergensis or Neanderthals reached Crete around 130,000 years ago, leaving hand axes behind and crossing water distances of approximately 40 km (Strasser et al., 2010).

Even more spectacular are the colonization events of Luzon in the Philippines, Socotra in the Indian Ocean, and Flores in Indonesia. The colonization of Luzon, evident from the discovery of Homo luzonensis dating back 67,000 years, required crossing the Huxley Line, another notable biogeographical barrier, involving a journey of at least 250 km from the nearest landmasses (Detroit et al., 2019). Evidence also suggests that Oldowan toolmakers reached Socotra several hundred thousand years ago, which would have required a sea journey of approximately 80 km from the African coast (Amirkhanov et al., 2009). Additionally, the colonization of Flores, marked by the discovery of Homo floresiensis, also known as the Hobbit, required a journey of around 30-40 km of open sea (Morwood, Oosterzee, & Sutikna, 2007).

It is likely that Socotra, Flores, and Luzon were places where more archaic human species could live relatively undisturbed for long periods. For instance, the discovery of Oldowan tools on Socotra, which first appeared around 2.6 million years ago and were made by the ancestors of Homo erectus, suggests a very ancient colonization of the island (Semaw, 2000; Amirkhanov et al., 2009). The first settlers on Flores and Luzon were also likely from species predating Homo erectus, based on analyses of the fossils of Homo floresiensis and Homo luzonensis, which exhibit some archaic features (Morwood, Oosterzee, & Sutikna, 2007; Detroit et al., 2019). Given that these are all very isolated islands, it is entirely possible that early hominids lived throughout much of Southeast Asia for extended periods but were eventually pushed out when Homo erectus settled in the region, surviving late only on islands far out at sea.

All this evidence indicates that humans have been well-acquainted with aquatic environments for a couple of million years and suggests that humans probably lived scattered throughout the maritime world of the Eurasian coastline. This is also a clear sign that they could build floating structures or boats to undertake these maritime journeys.

Clues from Kalambo Falls

One clue to how these early floating structures might have been constructed can be found at Kalambo Falls in Zambia. Archaeologists have discovered the oldest known wooden structures here, dated to around 476,000 years ago. These structures consist of two interlocking logs joined by an intentionally cut notch. The researchers behind this finding believe the structures were likely used as a stable platform in a wet environment, which may have included use as a raft or dock (Barham et al., 2023).

The preservation of these wooden structures was possible because they became waterlogged, meaning they were submerged in water and saturated, preventing decomposition by creating an anaerobic (oxygen-free) environment (Barham et al., 2023). This remarkable preservation provides further evidence of early humans’ ability to use wood to create structures for aquatic activities.

Surfer’s Ear: Evidence of Aquatic Adaptations in Early Humans

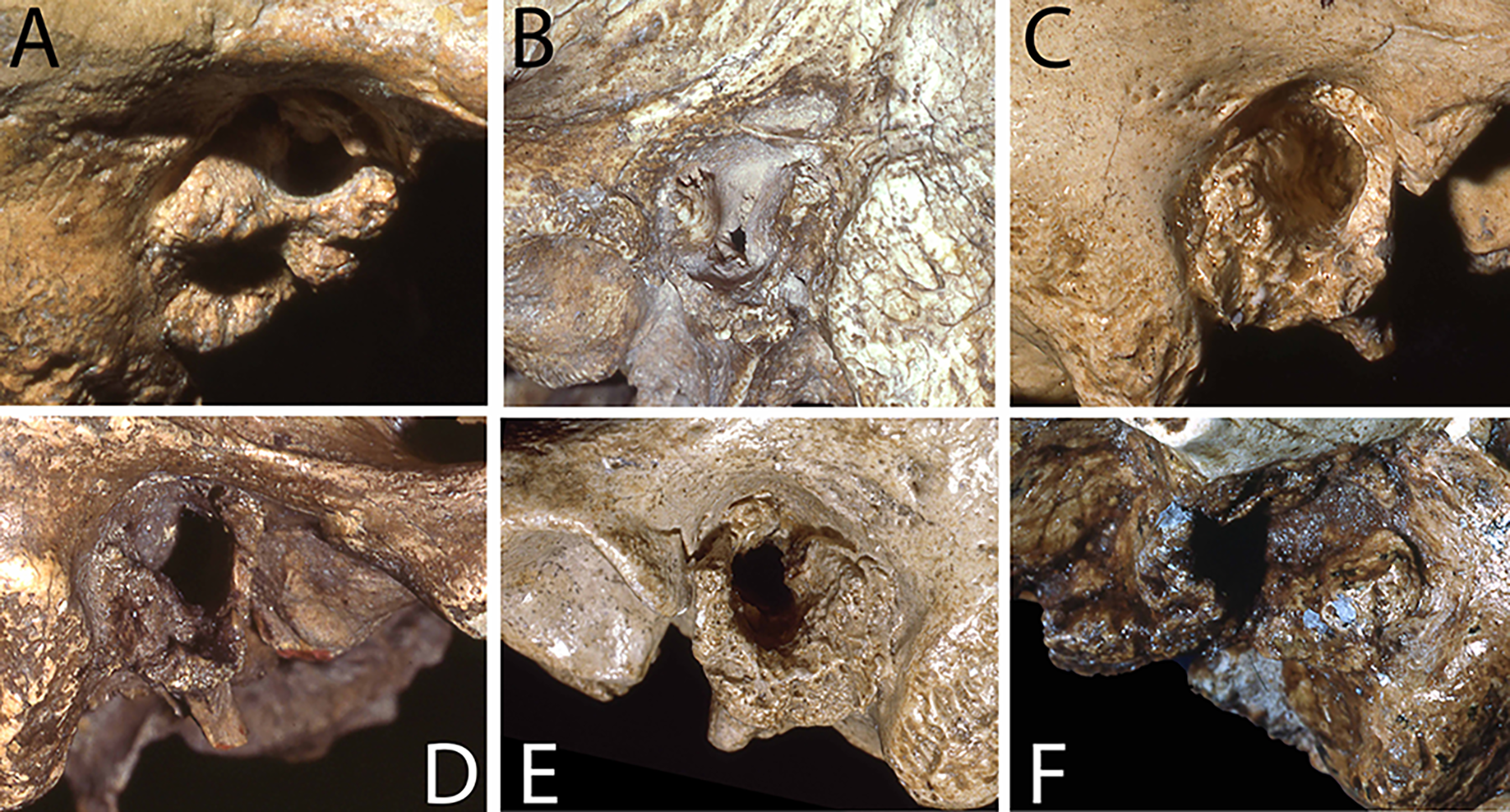

Surfer’s ear, or exostosis, is a bony growth in the ear canal that develops from prolonged exposure to cold water. Research by Trinkaus, Samsel, and Villotte (2019) has shown that a significant percentage of both Neanderthal and early Homo sapiens fossils in Eurasia exhibit this condition. In a study examining 77 fossils with well-preserved ear canals, it was found that these early humans were frequently in cold water environments, likely for marine foraging activities (Trinkaus, Samsel, & Villotte, 2019).

In the study, 48% of the Neanderthal specimens investigated had Surfer’s ear. While it was often difficult to determine their sex, among the identified Neanderthal women, three out of four had this condition (Trinkaus, Samsel, & Villotte, 2019). Similarly, Surfer’s ear was prevalent in Homo sapiens fossils, with approximately 25% of Middle Paleolithic specimens (300,000 to 30,000 years ago) showing the condition. The prevalence was 20.8% during the Early/Mid Upper Paleolithic (50,000 to 30,000 years ago) and dropped to 9.5% in the Late Upper Paleolithic (30,000 to 10,000 years ago), indicating a change in lifestyle (Trinkaus, Samsel, & Villotte, 2019).

Interestingly, in the 19 sexable Early/Mid Upper Paleolithic Homo sapiens specimens, Surfer’s ear was present in 16.7% of males and 28.6% of females. This suggests that more women than men exhibited this condition in early Homo sapiens (Trinkaus, Samsel, & Villotte, 2019). These findings support the hypothesis that women, due to their thicker layer of subcutaneous fat, were better suited to spending extended periods in water and were likely more involved in diving activities. This evidence highlights the significant role aquatic environments played in the lives of early humans.

Moreover, findings from Panama show that even people living in warm environments can develop Surfer’s ear when they engage in deep diving where the water is colder. This observation is supported by the analysis of fossils dating back thousands of years (Arias-Martínez et al., 2019), further emphasizing the connection between human activity and aquatic environments across different climates and time periods.

Conclusion

These pieces of evidence collectively paint a compelling picture of how early humans thrived in and around water. From navigating long distances over open seas to developing physiological adaptations to cold water environments, much also indicates that women were perhaps more involved than men in diving activities during this time.

As we uncover more about our past, it becomes clear that our relationship with water has profoundly shaped our evolution. These findings not only challenge previous notions about early human behavior but also open new avenues for understanding the complexities of our development. The future of exploring our aquatic heritage lies in continued research and the growing field of underwater archaeology, promising even more fascinating discoveries.

Literature

Amirkhanov, K. A., Zhukov, V. A., Naumkin, V. V., & Sedov, A. V. (2009). Эпоха олдована открыта на острове Сокотра. Pripoda, 7.

Arias-Martínez, L., González-Reimers, E., Velasco-Vázquez, J., Santolaria-Fernández, F., & Hernández-Moreno, M. (2019). Auditory exostoses and their relationship to environmental factors in the pre-Hispanic Canary Islands. American Journal of Physical Anthropology. https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/abs/10.1002/ajpa.23757.

Barham, L., et al. (2023). Earliest Evidence of Structural Use of Wood at Kalambo Falls. Nature. https://www.nature.com/articles/s41586-023-06557-9.

Detroit, F., Mijares, A. S., Piper, P., Grün, R., Bellwood, P., Aubert, M., … & Zeitoun, V. (2019). A new species of Homo from the Late Pleistocene of the Philippines. Nature, 568(7751), 181-186.

Morwood, M. J., Oosterzee, P. V., & Sutikna, T. (2007). The Discovery of the Hobbit: The Scientific Breakthrough that Changed the Face of Human History. Random House.

O’Connell, J. F., Allen, J., & Hawkes, K. (2010). Pleistocene Sahul and the Origins of Seafaring. Cambridge Archaeological Journal, 20(1), 69-84. doi:10.1017/S0959774310000055.

Strasser, T. F., Panagopoulou, E., Runnels, C. N., Murray, P. M., Thompson, N., Karkanas, P., … & Coleman, J. (2010). Stone Age seafaring in the Mediterranean: evidence from the Plakias region for Lower Palaeolithic and Mesolithic habitation of Crete. Hesperia: The Journal of the American School of Classical Studies at Athens, 79(2), 145-190.

Trinkaus, E., Samsel, M., & Villotte, S. (2019). External auditory exostoses (Surfer’s ear) in the human fossil record: A proxy for behavioral adaptations to aquatic resources. PLOS ONE, 14(8): e0220464. https://journals.plos.org/plosone/article?id=10.1371/journal.pone.0220464.

Exploring the Lives of the Sama Bajau: A Field Report from Sabah, Malaysia

Amidst the bustling activity of the Philippine night market in Kota Kinabalu, I found myself surrounded by the vibrant energy of fish vendors, children selling plastic bags, men and women in worn-out clothes transporting ice on wheelbarrows, and restaurant owners showcasing mantis shrimp and lobster in front of warm grills. This market, a microcosm of the larger economic struggles faced by the Sama Dilaut, became the starting point of my field trip to Sabah, Malaysia, aimed at collecting data for my thesis on the Sama Dilaut’s role in the economy and fishing industry.

At the turn of the year from 2022 to 2023, I embarked on this journey to delve into the lives and challenges of the Sama. Despite their hard work and exceptional fishing skills, they continually struggle with capital and opportunities, often finding themselves on the losing end of trade. To better understand their plight, I employed the “follow the thing” methodology, as elaborated by Appadurai, focusing on the seafood chain. Fish serve as a lens through which we can explore critical issues such as conservation, destructive fishing methods, and structural violence.

Kota Kinabalu: A Vibrant Market Scene

The trip began in Kota Kinabalu, the largest city and tourist hub in northern Sabah. This city hosts a bustling Philippine night market with various Sama Bajau groups from numerous Philippine Islands. The harbor, filled with trawlers, longliners, and shrimp boats, serves as a transit hub for fish trade. Across the water lies Pulau Gaya, home to many undocumented migrants from the Philippines. I engaged with local fish vendors, small seafood restaurant owners, Sama Dilaut children selling plastic bags, fish traders, boatmen, and more. As always, crowds gathered around me when they realized that I speak Sinama, often filming to boost their social media following. Common questions included how long I had been learning Sinama, if I could speak Malay or Tausug, if I was married and how much dowry is in my country.

One afternoon, I decided to visit Pondo on Pulau Gaya, which is designated a ‘no-go zone.’ At the informal jetty, I befriended a young Filipino man who helped me cross to Pondo, after carefully evading the Marine Police that controlled the area. We docked at Ridwan’s parents’ stilt house and walked towards the island, surrounded by excitement and friendly questions. A group of children followed us, asking for candy, which I promised to give later to avoid too much fuss. However, due to serious problems with drugs and glue-sniffing, it was unsuitable to stay long. After 30 minutes, we returned to the boat, bought candies for the kids, and headed back to the city.

Upon arrival, I found myself amidst a volleyball match between fish traders, who saw me arriving from the sea, leading to a relaxed atmosphere filled with questions and jokes.

Meetings with Stakeholders in Kota Kinabalu

In Kota Kinabalu, I met Terrence Lim, the director of Stop Fish Bombing Malaysia, an organization dedicated to combating destructive fishing methods. He shared insights into fish bombing, cyanide fishing, and the marginalization of the Sama Dilaut community. According to Terrence, “Fish trades can now be settled at sea. Everyone has a phone, and money is being sent online.” However, he explained that the Sama Dilaut cannot register SIM cards and are completely dependent on the informal cash-driven economy.

Terrence also mentioned, “Big fishing boats are using sonars for fishing, and there’s a growing concern about the difficulty of catching big fish, further marginalizing the Sama Dilaut community.” He further explained that the Sama Bajau are often on the losing end of negotiations, having to sell their fish quickly due to lack of storage and their statelessness.

Kudat: Exploring New Horizons

Next, I traveled to Kudat, located in the northernmost part of Sabah. The Tun Mustafa Marine Park is here, though it attracts fewer tourists compared to other popular destinations. My goal was to explore new areas where many Sama Dilaut from Semporna had moved in search of better opportunities. After purchasing ferry tickets—and taking photos with the young female vendors who recognized me from social media posts in Kota Kinabalu—I met the chief engineer, who shared insights about the area’s environmental issues, including pollution and acidification. Upon arrival, I realized that most residents were Ubian, a Sama group from an island near Tawi-Tawi in the Philippines.

I looked for someone to take me to Bankawan Island, east of Banggi, where Terrence had mentioned a recently established Sama Dilaut community. I met a group of older men who helped me find a boatman. Next morning, we drove towards a cluster of three anchored houseboats, and the people on them greeted us warmly with big smiles. One young father, holding his baby boy with a protective amulet around his neck and arm, pointed at me and said “melikan, melikan” while waving happily.

The meeting was full of contrasts. The father continued to socialize with his little child, who had likely seen a white person for the first time. This made it a special occasion for the Sama Dilaut, who generally hold white people in high regard, having had mostly positive experiences with them in the past. We talked about their fishing habits and how long they had been living in the area. The father on the boat said they had been there for a few years and showed me some shellfish and a lobster they were planning to sell in Karaket. A young boy wearing a Neymar Jr. t-shirt was fishing with a hook and line, while a young man standing on the roof of the larger houseboat asked for my phone number, holding up a mobile phone. They told me fishing was better in Kudat than in Semporna and that they didn’t plan to return to Semporna.

Before leaving, I offered cookies and money. We also spoke to other houseboats, learning about nearby Sama Dilaut communities around the Tun Mustafa Marine Park. We were invited to a water village, clearly visible on Google Earth, where we toured and saw sea cucumbers being farmed. The community consisted largely of undocumented migrants from the Philippines, making their living from fishing and fish farming.

Semporna: A Deep Dive into Local Life

The final destination was Semporna, where I have spent significant time during previous trips to Sabah. Over the years, I have established relationships with various people and places in Semporna, allowing me to gather valuable information. The central market, which had faced years of construction delays due to lack of funds and alleged corruption, was finally completed. However, it was mostly abandoned, with only the fruit and fish markets being utilized. The rest of the trade took place on small tables scattered around sidewalks and walkways, particularly in Kampung Air. Young boys had turned the new central market into a makeshift football field, giving the area an almost ghost-town feel.

Walking through Kampung Air, I noticed the bustling activity with small restaurants, cafes, and stalls selling various goods. The Sama Dilaut who had come to buy staples and sell fish were as always very silent, reflecting the everyday struggles they face, such as racism, poverty, statelessness, and difficulties in making a living at sea. All these challenges can be described as structural violence, a concept originally put forward by sociologist Johan Galtung. This violence has no clear beginning or end, and no single person to blame. It is embedded in the spaces in between—in the market, in the tone of the seller, in the waiting room at the health clinic, and in the long gazes on the street.This was later reflected when I stumbled across a few fishermen from Bangau Bangau who had brought in a sizable catch of cuttlefish. When I asked them how many days they had been out at sea, they replied, “Three days,” at which point the fish trader, who had just started to weigh their catch, said with disdain in his voice, “Sleeping, eating, and pooping on the boat,” whereupon the Sama men fell silent once again.

Further down the wooden bridges, I noticed dried moray eels being prepared for sale. A vendor explained that these eels are bought from fishermen for 5 RM (approximately $1.10 USD) per kilo, dried, and then sold for 15 RM (approximately $3.30 USD) per kilo in Tawau. This 200% increase in value highlights the inadequate compensation the Sama Dilaut receive for their livelihood.

At a nearby store selling fishing equipment, I observed items reflecting various fishing methods used in the area—spear gun fishing, hook and line fishing, net fishing, and compressor diving. The new fish market near Kampung Air was lively, with many people recognizing me from previous visits. The market offered a wide variety of fish, and I engaged with children selling plastic bags, who were amazed that I could speak Sinama.

Exploring Sama Villages and Marine Life with Sabah Parks

Following Sabah Parks on one of their tours, I visited the Sama Dilaut village of Tatagan, located at the foot of Mount Bod Gaya in the Tun Sakaran Marine Park. Despite tensions between Sabah Parks and the village, I met Kirihati, one of the few who still live on larger houseboats. He shared his experiences and the challenges of maintaining this traditional way of life. Kirihati was growing medicinal plants on the roof of his houseboat, and on land, he was in the process of building a new houseboat with the help of a skilled boat builder.

Later, we visited Bohey Dulang, where Sabah Parks had an exhibition about marine life, including an albino turtle—a rare and fascinating sight. The caretaker was thrilled to show us this unique addition to their collection, explaining that albino turtles are extremely rare.

The final stop was the paradise island of Sibuan, home to a small group of Sama Dilaut, Malaysian soldiers, and Sabah Park rangers. On Sibuan, we stumbled upon a Photo Safari session. Two overly talkative and enthusiastic interpreters, who were themselves Sama Bajau, urged all the Sama Dilaut children to line up. A group of tourists from the Malaysian mainland then handed out snacks to the children. Afterwards, mandatory photography ensued, and I was invited to participate.

Following Terence on a Busy Work Day

While in Semporna, I joined Terence, who had come down from Kota Kinabalu, on a day trip to check on his bomb-detecting sensors scattered throughout the area. Stop Fish Bombing Malaysia has over 10 sensors covering a large part of the sea. Terence explained that the number of explosions had dramatically decreased, especially near Bum Bum Island. However, some sensors had been bombed by fishermen who opposed the initiative. We also checked on a radar installed on Sanlakan Island, which helps track boats involved in fish bombing.

Visit to Bangau Bangau

One day, I visited Bangau Bangau, home to many Sama Dilaut who arrived from Sitangkai in the Philippines in the 1960s. Most villagers now have Malaysian Identity Cards, but many who came later remain undocumented. Some of the residents have become middlemen in the fishing trade or taken on regular jobs, with their cars parked next to the water bridges, while others continue as traditional fishermen.

I reconnected with an old friend, Si Wanti, a former boat driver who had taken me out to sea many times in the past. Now, he makes a living from small-scale net fishing. I gave him shark and coral fish posters in Sinama, which fascinated many of the elders. An old man living in the same compound as Wanti was particularly happy to see the shark poster. When I read out the names of the sharks to him, he was amazed that I even knew their names. He looked at the collage for a long time, identifying the sharks one after another. He was impressed that all the sharks had been put together in one photo and remarked that the person who took the photos must be very brave.

Reflections and Key Takeaways

Throughout my trip, I learned more about the fish value chain. For instance, moray eels are bought for 5 RM per kilo and sold for 15 RM per kilo in Tawau, representing a 200% increase in value. It’s clear that the Sama Dilaut are not adequately compensated for their hard work. They dive and fish under harsh conditions, only to sell their catch for a pittance, benefiting middlemen and end consumers who enjoy seafood at low prices. Industrial fishing forces down prices, leaving subsistence fishermen and the environment to pay the ultimate price.

People are constantly pushed to their limits, driven by physical needs and market forces. While only those higher up the value chain may become wealthy, the majority must keep pushing themselves and their environment daily. Despite the hardships, the Sama Dilaut have a deep fascination and love for the sea. They cherish moments of peace with their loved ones, swaying with the waves and watching the sunset after a fulfilling meal. However, their constant struggle for survival amidst harsh conditions places them in the grip of structural violence.

Fish serve as a lens through which we can explore important issues such as conservation, destructive fishing methods, and the structural violence faced by the Sama Dilaut. Despite their hard work and fishing skills, the Sama Dilaut continually struggle with capital and opportunities, often losing out in the economic trade. Most Sama Dilaut today live near marine national parks like Tun Sakaran Marine Park in Semporna and Tun Mustafa Marine Park in Kudat. These areas prohibit large-scale fishing, creating a niche for Sama Dilaut and other groups.

However, competition is intense, and resources are limited. Coral bleaching is already a concerning development in the area, threatening the delicate marine ecosystems that the Sama Dilaut depend on for their livelihood. Their resilience and deep connection to the sea highlight the need for greater support and sustainable practices to preserve their way of life and the marine environment they depend on. Ensuring the sustainability of these ecosystems is crucial not only for the Sama Dilaut but for the broader health of our oceans.

The resilience and deep connection to the sea exhibited by the Sama Dilaut, despite the immense challenges they face, underscore the urgent need for greater support and sustainable practices. By preserving their way of life and the delicate marine environment they depend on, we not only honor their rich cultural heritage but also safeguard the health of our oceans for future generations. Their story is a powerful reminder of the intricate bond between humans and nature, and the critical importance of fostering both community and environmental sustainability.

Life of Sama Dilaut – Broken Eardrums, Spear Gun Fishing and Indebtedness

From the end of December 2016 to the beginning of February 2017 I travelled in Philippines, Malaysia and Indonesia where I visited several Sama Dilaut communities. I talked to them about their daily lives, followed fishing and continued to learn the basics of two of their dialects, Central Sinama and Indonesian Bajo.

Noah – one of the last young boys who make a living from spearfishing in Davao

The trip started in Matina Aplaya in the outskirts of the metropolis Davao City in southern Philippines. Fish is on the decline and most people in the village make a living from vending of pearls, second hand clothes and shoes. However, a few families still make a living from the sea, and they are incredible divers.

I have been visiting Matina Aplaya every year since 2010 and I have always been accompanied by Issau and his son Noah. Noah is one of the few boys in the village who has grown up becoming a skin diver along with his father. On daily fishing expeditions, they spear fish and collect sea urchins, sea shells and clams in the coral reefs surrounding the town. It is fascinating to see that Noah has grown up to become a skilled fisherman who contributes to the household with his spear gun.

Zamboanga – Sama Dilaut resettlement after the 2013 fire

In 2013, the outskirts of Zamboanga were struck by a fire that destroyed thousands of houses and displaced thousands of Sama Dilaut and Tausug people. For months, they were living in a temporary camp in a sport arena close to the town centre.

After my visit in Davao, I made a two-day stopover in Zamboanga in western Mindanao before travelling to Tawi-Tawi. I visited some newly constructed villages set up by NGO:s and local authorities exclusively for the Sama, and many of the houses have been built in a traditional way. However, the daily life of many Sama Dilaut in Zamboanga is tough and it is getting harder and harder to make a living from the ocean. Many people are begging in the harbour. Yet others have fled to other cities in the Philippines.

Sitangkai – traditional dance in the Venice of the south

Despite recent kidnapping incidents in the Sulu I decided to travel to Tawi-Tawi in southwestern Philippines. I visited the Sama Study Center and the Marine museum in Tawi-Tawi where I met Rasul M. Sabal, the museum director. He has a keen interest in Sama Dilaut culture and show sincere concern with their challenges.

While in Tawi-Tawi I took the opportunity to pay a visit to Sitangkai along with Rasul M. Sabal and two policemen. Over the last years, very few foreigners have been in the area and I was fortunate to be able to visit the legendary community where thousands of people live in what is called the “Venice of the south” next to a tiny piece of land.

In Sitangkai, Sama elders performed religious dance that is normally performed during the magpai baha’u ceremony, an annual ritual taking place once a year in community (this year it will be held in May and it attracts Sama people from all over Sulu and Sabah). It was great to experience their hospitality and kindness!

I came to know that the interaction between Sabah and southern Philippines is intense despite stricter migration policies on the Malaysian side, and boats are heading between the locations more or less every night. In Sitangkai, I also saw how octopuses were shipped on a large scale to Tawi-Tawi and further to Zamboanga and Manila. However, the production of sea weeds has dropped due to reduced market prices.

Broken eardrums

After Tawi-Tawi, the initial plan was to take a ferry to Semporna, but the ferry company had lost its license so I took another ferry going back to Zamboanga instead. In the harbour of Bongao, more than 20 Sama Dilaut children were diving for coins, displaying great skills.

On the trip back to Zamboanga, I met two Sama brothers from Tawi-Tawi who were on their way to Palawan to join a fishing crew going deep in the South China Sea. They told me that they usually made use of explosives and compressors during these trips, and that the expeditions used to last for about one month. I asked them about their eardrums, and they said that they had broken them. Then, I asked them about their hearing ability, and they told me that their hearing was okay but that they had problems localising sounds. The brothers’ story is interesting since it has been unclear whether Sama fishermen break their eardrums or not. I would say that most the Sama Dilaut divers permanently rupture their eardrums, either on purpose or accidentally, and they take medicine in the case of infection. However, some fishermen do also equalize their ears and some may have hands free techniques for doing so.

When the ferry arrived in Zamboanga day after, the scene changed. Nearly 100 Sama begged for money in the harbour, including elders, and the atmosphere was more tense than in Bongao. It got obvious that life is very difficult in Zamboanga, and it is not surprising that so many Sama Dilaut are now roaming the cities of Manila, Cebu and other Philippine cities.

Meeting with Sulbin on Mabul

After the trip to Sulu, I made a short stop in Semporna where I went to Mabul to meet the Sama community there. I was lucky to meet Sulbin – the diver who walks on the sea floor for nearly two minutes in a widespread BBC production. He told m e that he had just come back from seasonal work in Kota Kinabalu. Hence, also the most skilled fishermen might choose to make a living in the job market rather than make their own fishing trips in the region!

e that he had just come back from seasonal work in Kota Kinabalu. Hence, also the most skilled fishermen might choose to make a living in the job market rather than make their own fishing trips in the region!

However, in Semporna many Sama Dilaut still live in houseboats and they roam the many islands in search of fish, sea shells, clams, sea urchins and so on. Many of the more traditional Sama have no option but to continue extracting resources from the ocean.

Sama Dilaut spear-gun fishing women Wakatobi

After the short stop in Malaysia, I went on to Makassar in Indonesia where I met up with Professor Erika Schagatay from Mid-Sweden University, for our third trip together. We headed towards the island of Buton in southern Sulawesi where we spent a few days in the village of Topa (the sama village where Erika Schagatay first came in contact with Sama people in 1988). In the village, we followed fishing, talked to the people and made physiological research on Sama divers. For example, we measured the diver’s lung capacity, spleen size and feet size.

After the stay in Topa, we took a ferry to Wangi-Wangi in the Wakatobi island group. We spent one day in Wangi-Wangi before we visited the village of Samepla further out in the archipelago, where we spent four days. Sampela is located more than one hundred meters from the island of Kaledupa and have got attention in several film projects throughout the years, in for example BBC:s series “Hunters of th e South Seas” and the movie “The Mirror Never Lies”. During our stay in the village, we joined a group of women spearfishing, and it was fascinating to see their acquaintance with the ocean. We also followed fishing with Tadi, a 70-year-old fisherman who is still an incredible fisherman. He was the most successful fisherman during our trips, outperforming much younger spear gun fishermen. We also got the opportunity to measure Tadi’s spleen, and it turned out that his spleen is much bigger than peoples at the same age and with the same body size, and whom do not make a living from diving. The spleen is a very critical organ for experienced divers, since it consists of a high concentration of blood cells that can be released under pressure.

e South Seas” and the movie “The Mirror Never Lies”. During our stay in the village, we joined a group of women spearfishing, and it was fascinating to see their acquaintance with the ocean. We also followed fishing with Tadi, a 70-year-old fisherman who is still an incredible fisherman. He was the most successful fisherman during our trips, outperforming much younger spear gun fishermen. We also got the opportunity to measure Tadi’s spleen, and it turned out that his spleen is much bigger than peoples at the same age and with the same body size, and whom do not make a living from diving. The spleen is a very critical organ for experienced divers, since it consists of a high concentration of blood cells that can be released under pressure.

Also in Sampela, life is getting more and more difficult because of decline in fish. In the community, there is also a problem of indebtedness and large interest rates. Hence, many Sama fishermen are forced to increase fishing efforts despite recent decline in marine resources. Or in other words, they live on resources yet to be extracted.

Sampela is located within the Wakatobi National Park, but nevertheless, too little is done to prevent over-exploitation of the area. Big fishing boats enter the waters even though only small scale fishing methods are allowed. Hence, more must be done to reinforce the park regulations and to protect the area and the people living there.

Kabalutan – a pregnant woman showing great diving skills

My last visit in Indonesia took place in the community of Kabalutan in the Gulf of Tomini, central Sulawesi. Also this community is known from a few TV productions. Here, BBC produced a short documentary about Sama Dilaut with Tanya Streeter in 2007, in which young Sama children dive 12 meters repeatedly displaying great skills. This is also the place where Svea Andersson’s depicts a eight month pregnant woman diving for shell fish in the movie “Sulawesi, the last sea nomads”.

Along with two Sama families, I followed on a pongka fishing trip – a fishing trip at sea lasting for a few days. We stayed two nights at sea, collecting shell fish and spear-gunned fish. Among those who followed were 17 year old Muspang, the youngest boy in BBC:s movie with Tanya Streeter He is already a father and a great diver. However, I was more impressed by his mother, the same woman that was highlighted in Svea Andersson’s movie. Again pregnant, she was diving up to eight meters in search for shell fish and clams, as well as spear gun fishing. She is one of the last free diving Sama women with great diving abilities; one of the few remaining in not only Kabalutan but most likely in most Sama communities throughout Southeast Asia.

trip at sea lasting for a few days. We stayed two nights at sea, collecting shell fish and spear-gunned fish. Among those who followed were 17 year old Muspang, the youngest boy in BBC:s movie with Tanya Streeter He is already a father and a great diver. However, I was more impressed by his mother, the same woman that was highlighted in Svea Andersson’s movie. Again pregnant, she was diving up to eight meters in search for shell fish and clams, as well as spear gun fishing. She is one of the last free diving Sama women with great diving abilities; one of the few remaining in not only Kabalutan but most likely in most Sama communities throughout Southeast Asia.

However, the amount of large commercial fish in on the decline also in Kabalutan, and it will be difficult for Sama people to sustain a living at the sea. Shell fish and octopus are still in quite big numbers since they mostly are being extracted using traditional fishing methods including diving, but other fish are rare. Who knows what life will look like after just 10 years when the consequences of coral bleaching and rising ocean temperatures will be much more severe than today?

The Placenta is Thrown into the Ocean

Bajau Laut have been living in Southeast Sulawesi since the 16th century. Originally, they were involved in the spice trade, transporting lucrative spices from Moluccas to Borneo. When the Dutch colonialists changed the trade routes many Bajau Laut stayed on their houseboats made a living completely from sea harvesting. Some do still today.

WWF in Wakatobi

Most Bajau villages on Buton and Wakatobi in Southeast Sulawesi were created only one or two generati ons ago, when Bajau sea nomads settled in pile houses.

ons ago, when Bajau sea nomads settled in pile houses.

In one of the villages of Buton, Lasalimu, I met Sadar, a Bajau who works for WWF in Wakatobi. His work is to persuade Bajau fishermen stop dynamite fishing. “In Wakatobi we have been quite successful but further north many Bajau use fish bombs and cyanide”.

In Wakatobi most fishermen make a living from skin diving, as compressors are illegal. “We also try to regulate how much fish they can catch a day”, Sadar told me, “it is necessary because they are fishing in Wakatobi National Park”.

Sadar also told me that it still is practice among some Bajau to throw the placenta in the ocean after giving birth. They believe that the child will protect the sea as “it is the home of their sibling”. You can read more in this article in Al Jazeera: Indonesia’s last nomadic sea gypsies (2012-10-06).

Born on the sea

After my visit in Buton I headed north to Lasolo where many Bajau Laut are living on small, isolated islands. Around these islands, many Bajau used to live on the boats till only a few years ago. More or less everyone above 10 years old were born on the sea.

The author of Outcasts of the Islands, Sebastian Hope, visited Lasolo in the last decade and met sea nomads close to Boenaga and island of Labengke in Lasolo. But today all of them are living in houses.

In the Gulf of Togian in northern Sulawesi, however, it is still possible to find Bajau Laut who have been on the boat their entire lives.

Sama Language – spread over the Coral Triangle

Throughout The Coral Triangle you can find pockets of Sama communities, distinctive from the surrounding society, but speaking more or less the same language as other Sama groups living miles away.

It has been very interesting to be able to meet Sama people in Philippines, Malaysia and Indonesia and compare their dialects. As a matter of fact, there are still many similarities in their languages. For example, most words related to their maritime lifestyle are identical in all dialects I have encountered, like “amana” (spear-gun fishing) “messi” (hook-and-line fishing), “anga ringi” (netfishing), “e‘bong” (dolphin), “kalitan” (shark), “bokko´” (turtle), “gojak” (waves), “mosaj” (to paddle).

During my next Indonesian trip I would like to visit Flores, not far from Australia … probably they will speak a similar dialect here as well… But that will be explored during another journey. Now I am heading back to Semporna.