Hard Evidence of Early Human Seafaring and Women’s Role in Marine Foraging

New and fascinating discoveries provide hard evidence for the Aquatic Ape theory, evidence that was not known when Alister Hardy and Elaine Morgan first advocated for this idea. There is now substantial data proving that early humans undertook long maritime journeys, developed unique physiological adaptations, and lived lives closely tied to water. In this blog post, I will examine some of the compelling evidence that supports a semi-aquatic past for humans. These pieces of evidence meet the stringent criteria set by the anthropological community, which demands archaeological proofs for our evolutionary history, rather than merely examining our own bodily adaptations.

Long Early Maritime Journeys

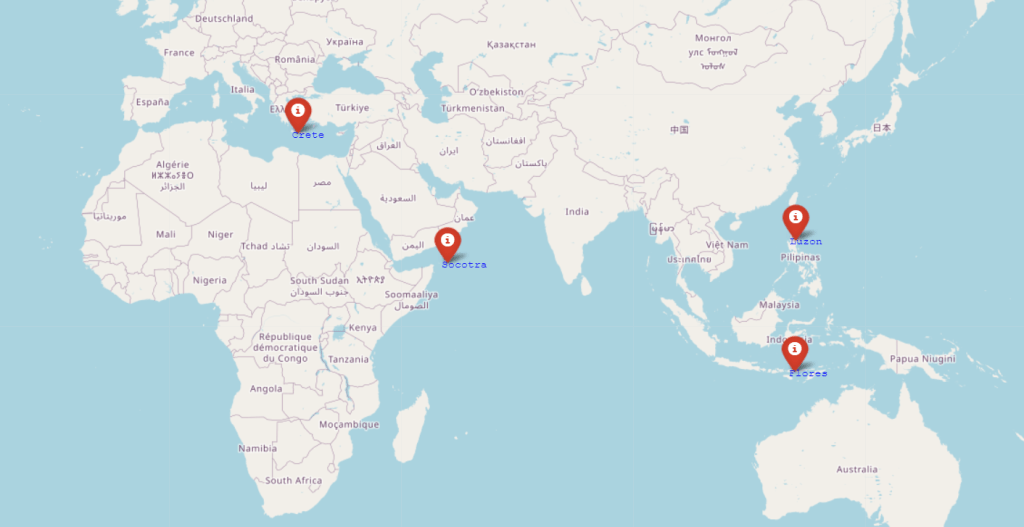

Early human species undertook impressive sea voyages, as evidenced by discoveries of human fossils and stone tools on distant islands that have been separated from the mainland for millions of years. For instance, Homo sapiens reached Australia about 65,000 years ago, a journey that required crossing at least 70-100 km of open sea from Indonesia, traversing the significant biogeographical barrier known as Wallace Line (O’Connell, Allen, & Hawkes, 2010). Similarly, Homo heidelbergensis or Neanderthals reached Crete around 130,000 years ago, leaving hand axes behind and crossing water distances of approximately 40 km (Strasser et al., 2010).

Even more spectacular are the colonization events of Luzon in the Philippines, Socotra in the Indian Ocean, and Flores in Indonesia. The colonization of Luzon, evident from the discovery of Homo luzonensis dating back 67,000 years, required crossing the Huxley Line, another notable biogeographical barrier, involving a journey of at least 250 km from the nearest landmasses (Detroit et al., 2019). Evidence also suggests that Oldowan toolmakers reached Socotra several hundred thousand years ago, which would have required a sea journey of approximately 80 km from the African coast (Amirkhanov et al., 2009). Additionally, the colonization of Flores, marked by the discovery of Homo floresiensis, also known as the Hobbit, required a journey of around 30-40 km of open sea (Morwood, Oosterzee, & Sutikna, 2007).

It is likely that Socotra, Flores, and Luzon were places where more archaic human species could live relatively undisturbed for long periods. For instance, the discovery of Oldowan tools on Socotra, which first appeared around 2.6 million years ago and were made by the ancestors of Homo erectus, suggests a very ancient colonization of the island (Semaw, 2000; Amirkhanov et al., 2009). The first settlers on Flores and Luzon were also likely from species predating Homo erectus, based on analyses of the fossils of Homo floresiensis and Homo luzonensis, which exhibit some archaic features (Morwood, Oosterzee, & Sutikna, 2007; Detroit et al., 2019). Given that these are all very isolated islands, it is entirely possible that early hominids lived throughout much of Southeast Asia for extended periods but were eventually pushed out when Homo erectus settled in the region, surviving late only on islands far out at sea.

All this evidence indicates that humans have been well-acquainted with aquatic environments for a couple of million years and suggests that humans probably lived scattered throughout the maritime world of the Eurasian coastline. This is also a clear sign that they could build floating structures or boats to undertake these maritime journeys.

Clues from Kalambo Falls

One clue to how these early floating structures might have been constructed can be found at Kalambo Falls in Zambia. Archaeologists have discovered the oldest known wooden structures here, dated to around 476,000 years ago. These structures consist of two interlocking logs joined by an intentionally cut notch. The researchers behind this finding believe the structures were likely used as a stable platform in a wet environment, which may have included use as a raft or dock (Barham et al., 2023).

The preservation of these wooden structures was possible because they became waterlogged, meaning they were submerged in water and saturated, preventing decomposition by creating an anaerobic (oxygen-free) environment (Barham et al., 2023). This remarkable preservation provides further evidence of early humans’ ability to use wood to create structures for aquatic activities.

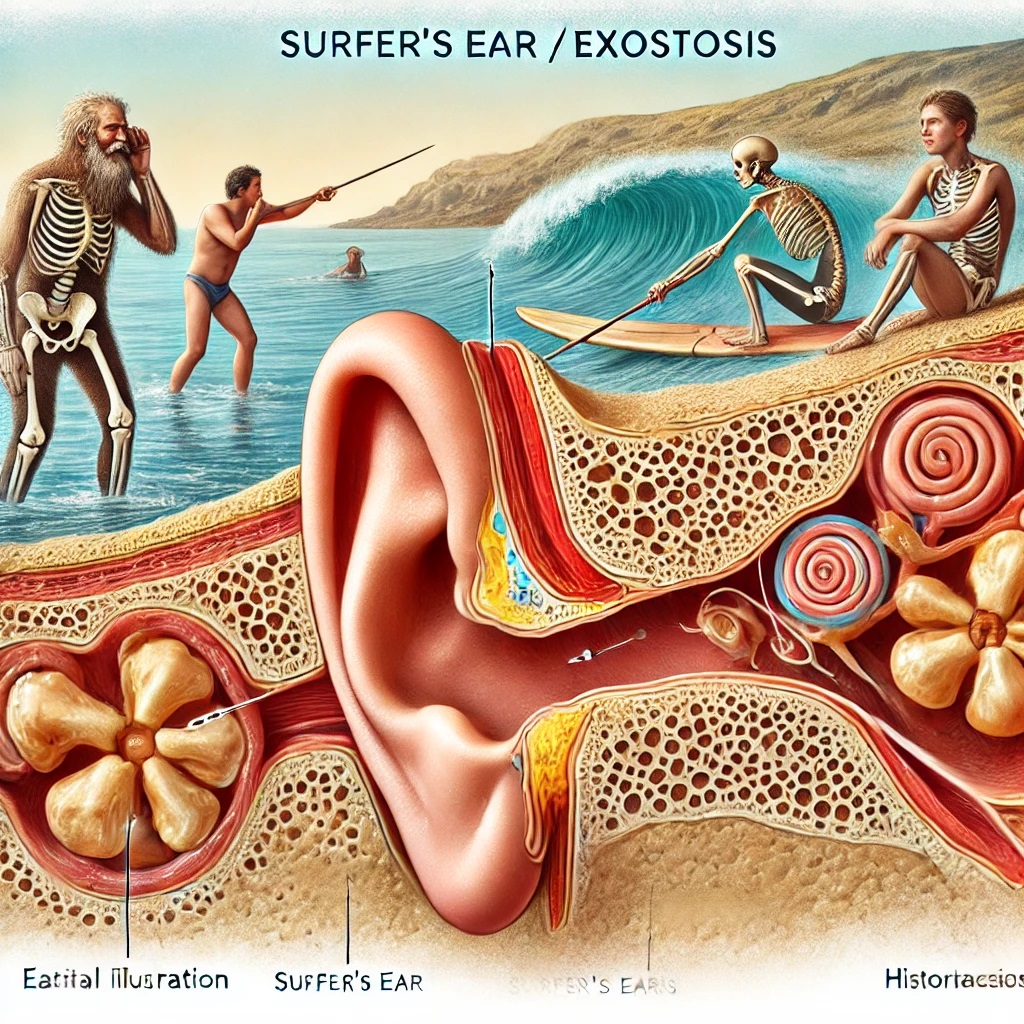

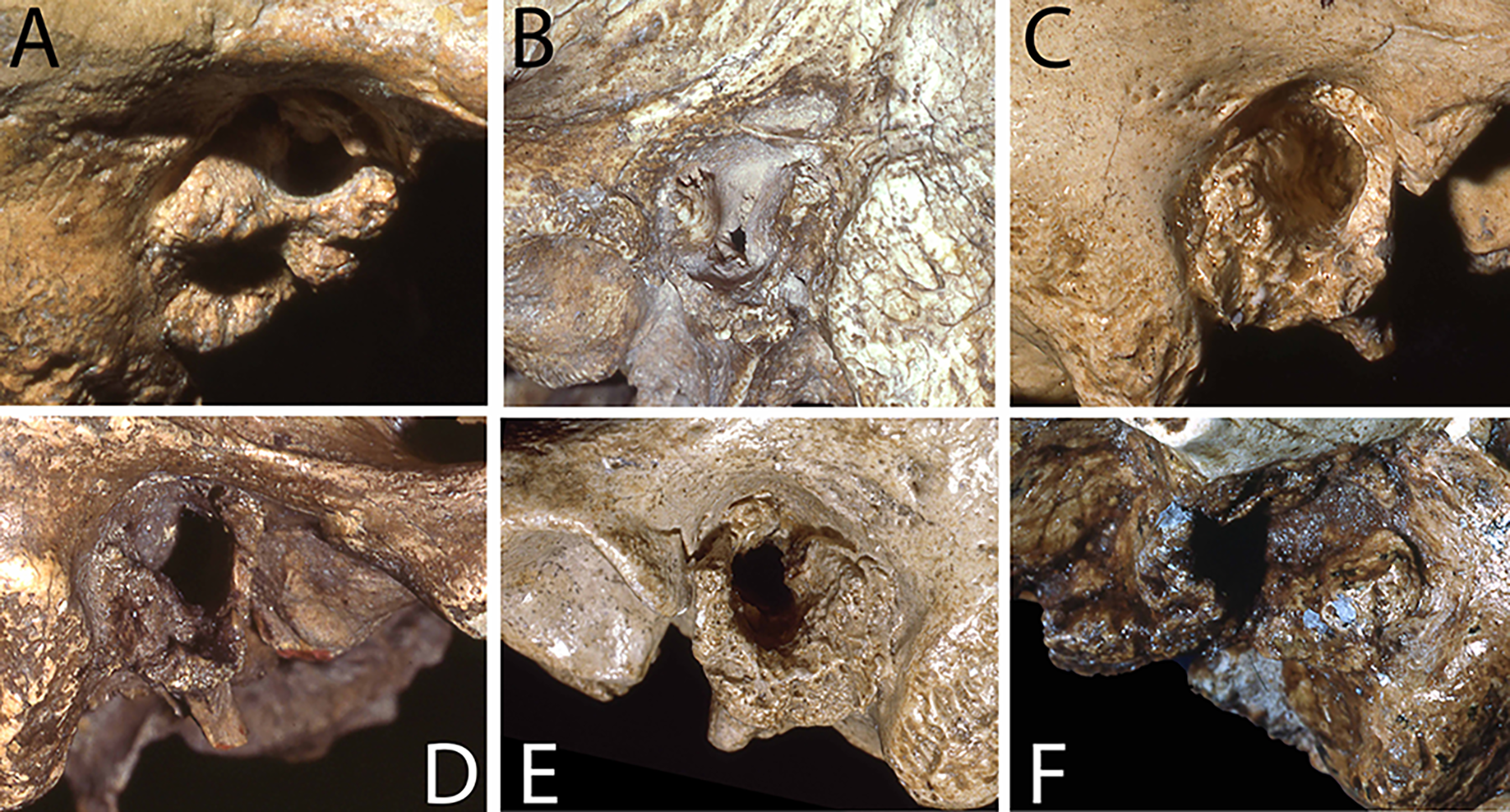

Surfer’s Ear: Evidence of Aquatic Adaptations in Early Humans

Surfer’s ear, or exostosis, is a bony growth in the ear canal that develops from prolonged exposure to cold water. Research by Trinkaus, Samsel, and Villotte (2019) has shown that a significant percentage of both Neanderthal and early Homo sapiens fossils in Eurasia exhibit this condition. In a study examining 77 fossils with well-preserved ear canals, it was found that these early humans were frequently in cold water environments, likely for marine foraging activities (Trinkaus, Samsel, & Villotte, 2019).

In the study, 48% of the Neanderthal specimens investigated had Surfer’s ear. While it was often difficult to determine their sex, among the identified Neanderthal women, three out of four had this condition (Trinkaus, Samsel, & Villotte, 2019). Similarly, Surfer’s ear was prevalent in Homo sapiens fossils, with approximately 25% of Middle Paleolithic specimens (300,000 to 30,000 years ago) showing the condition. The prevalence was 20.8% during the Early/Mid Upper Paleolithic (50,000 to 30,000 years ago) and dropped to 9.5% in the Late Upper Paleolithic (30,000 to 10,000 years ago), indicating a change in lifestyle (Trinkaus, Samsel, & Villotte, 2019).

Interestingly, in the 19 sexable Early/Mid Upper Paleolithic Homo sapiens specimens, Surfer’s ear was present in 16.7% of males and 28.6% of females. This suggests that more women than men exhibited this condition in early Homo sapiens (Trinkaus, Samsel, & Villotte, 2019). These findings support the hypothesis that women, due to their thicker layer of subcutaneous fat, were better suited to spending extended periods in water and were likely more involved in diving activities. This evidence highlights the significant role aquatic environments played in the lives of early humans.

Moreover, findings from Panama show that even people living in warm environments can develop Surfer’s ear when they engage in deep diving where the water is colder. This observation is supported by the analysis of fossils dating back thousands of years (Arias-Martínez et al., 2019), further emphasizing the connection between human activity and aquatic environments across different climates and time periods.

Conclusion

These pieces of evidence collectively paint a compelling picture of how early humans thrived in and around water. From navigating long distances over open seas to developing physiological adaptations to cold water environments, much also indicates that women were perhaps more involved than men in diving activities during this time.

As we uncover more about our past, it becomes clear that our relationship with water has profoundly shaped our evolution. These findings not only challenge previous notions about early human behavior but also open new avenues for understanding the complexities of our development. The future of exploring our aquatic heritage lies in continued research and the growing field of underwater archaeology, promising even more fascinating discoveries.

Literature

Amirkhanov, K. A., Zhukov, V. A., Naumkin, V. V., & Sedov, A. V. (2009). Эпоха олдована открыта на острове Сокотра. Pripoda, 7.

Arias-Martínez, L., González-Reimers, E., Velasco-Vázquez, J., Santolaria-Fernández, F., & Hernández-Moreno, M. (2019). Auditory exostoses and their relationship to environmental factors in the pre-Hispanic Canary Islands. American Journal of Physical Anthropology. https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/abs/10.1002/ajpa.23757.

Barham, L., et al. (2023). Earliest Evidence of Structural Use of Wood at Kalambo Falls. Nature. https://www.nature.com/articles/s41586-023-06557-9.

Detroit, F., Mijares, A. S., Piper, P., Grün, R., Bellwood, P., Aubert, M., … & Zeitoun, V. (2019). A new species of Homo from the Late Pleistocene of the Philippines. Nature, 568(7751), 181-186.

Morwood, M. J., Oosterzee, P. V., & Sutikna, T. (2007). The Discovery of the Hobbit: The Scientific Breakthrough that Changed the Face of Human History. Random House.

O’Connell, J. F., Allen, J., & Hawkes, K. (2010). Pleistocene Sahul and the Origins of Seafaring. Cambridge Archaeological Journal, 20(1), 69-84. doi:10.1017/S0959774310000055.

Strasser, T. F., Panagopoulou, E., Runnels, C. N., Murray, P. M., Thompson, N., Karkanas, P., … & Coleman, J. (2010). Stone Age seafaring in the Mediterranean: evidence from the Plakias region for Lower Palaeolithic and Mesolithic habitation of Crete. Hesperia: The Journal of the American School of Classical Studies at Athens, 79(2), 145-190.

Trinkaus, E., Samsel, M., & Villotte, S. (2019). External auditory exostoses (Surfer’s ear) in the human fossil record: A proxy for behavioral adaptations to aquatic resources. PLOS ONE, 14(8): e0220464. https://journals.plos.org/plosone/article?id=10.1371/journal.pone.0220464.

Exploring Human Evolution: Visit at The Max Planck Institute in Leipzig

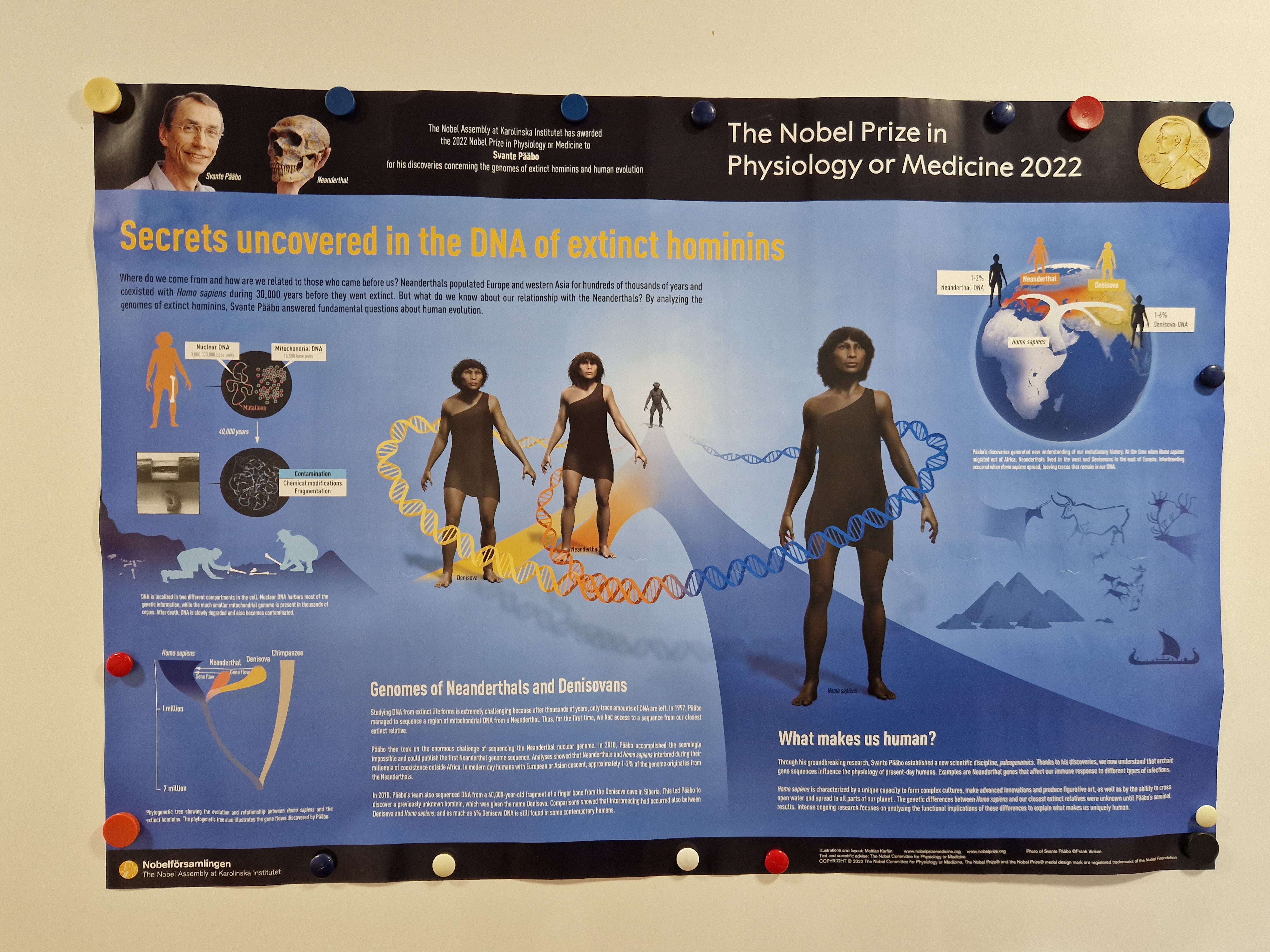

From May 22nd to May 24th, I had the opportunity to travel to Leipzig, Germany, where I visited the Max Planck Institute for Evolutionary Anthropology and met with PhD student Jae Rodriguez. This visit was both educational and inspiring, offering insights into the world of evolutionary anthropology and the fascinating research being conducted at this renowned institution. Only six months before my visit, Svante Pääbo, the director of the Department of Evolutionary Genetics at the institute, had been awarded the Nobel Prize in Medicine for his groundbreaking work on Neanderthal genomes (Nobel Prize, 2022).

During my stay, I gave a presentation on the Bajau Laut titled “Sama Bajau: Lifestyle, History, Evolution” to a group of students, postdocs and senior scientists as part of their “Ocean’s Meeting” series. In my presentation, I delved into their rich history, cultural significance, and the political factors influencing their way of life. Additionally, I explored the physiological aspects of their connection to the sea, such as their remarkable sense of well-being while living on the water. Scientific studies support this connection, showing that the rocking of waves improves sleep quality (Perrault et al., 2019), natural water sounds enhance relaxation (Gould van Praag, 2017), consuming marine food improves sleep quality (St-Onge, 2016), and more.

Jae Rodriguez, the PhD student who hosted me, focuses his research on the genetic origins and adaptations of the indigenous inhabitants of the Sulu Archipelago in the Philippines. A significant part of Jae’s research involves samples from over 2,000 Sama Bajau individuals in the southwestern Philippines, particularly around Tawi-Tawi, which are carefully stored in one of the institute’s labs. This material is crucial for mapping the Sama Bajau’s history and gaining a broader understanding of their genetic adaptations and unique lifestyle. It would be fascinating to delve deeper into the genetic sequences related to spleen size that Melissa Ilardo studied when she researched Bajau Laut divers in central Sulawesi, Indonesia. She found that the Bajau Laut in the area had undergone natural selection for larger spleens over at least a few thousand years (Ilardo et al., 2018).

I first met Jae Rodriguez at a conference in the Philippines in 2015, and we have kept in touch since then. It was a true pleasure to meet up with Jae in Leipzig and discuss the Bajau’s history, lifestyle, evolution, and future challenges, as well as other aspects of human evolution.

Jae also gave me a tour of the Max Planck Institute, including an exhibition on the ground floor about human history. I was looking forward to meeting Svante Pääbo, who also hails from Sweden, but despite his office being wide open, he was not around at the time. Outside his office, a Neanderthal skeleton was on display. Pääbo was the first scientist to sequence the entire genome of a Neanderthal, proving that Homo sapiens and Neanderthals had shared offspring, which has medical implications still today (Pääbo et al., 2010). A few years later, he also sequenced Denisovan DNA, revealing genetic traces in modern humans, particularly in Southeast Asian island populations, where up to 5% of some groups’ genes come from Denisovans (Reich et al., 2011). These discoveries have changed our understanding of the complexity of human evolution and made us realize how similar we are to our closest cousins who live on within us.

The institute itself is a dream destination for anyone interested in human evolution. It brings together scientists from diverse fields, including natural sciences and humanities, to investigate human history through interdisciplinary research. Their work includes comparative analyses of genes, cultures, cognitive abilities, languages, and social systems of both past and present human populations, as well as primates closely related to humans. The institute also hosts young doctoral students from around the world who delve into historical and genetic research from their own regions (Max Planck Institute for Evolutionary Anthropology).

My visit to the Max Planck Institute for Evolutionary Anthropology was a remarkable journey into the depths of human history and genetics. The opportunity to share my research on the Bajau Laut, explore cutting-edge scientific work, and connect with passionate scholars made this trip an unforgettable experience. As the field of genetics rapidly develops, new methods for analyzing ancient fossils will hopefully emerge. These new findings will reveal that even more populations have contributed to who we are today, making us even more humble about our origins and who we are.

References

Gould van Praag, C. D. et al. (2017). “The Influence of Natural Sounds on Attention and Mood.” Scientific Reports. Retrieved from nature.com.

Ilardo, M. A. et al. (2018). “Physiological and Genetic Adaptations to Diving in Sea Nomads.” Cell. Retrieved from cell.com.

Max Planck Institute for Evolutionary Anthropology. “About Us.” Retrieved from eva.mpg.de.

Max Planck Institute for Evolutionary Anthropology. “Prof. Dr. Svante Pääbo.” Retrieved from eva.mpg.de.

Nobel Prize. “The Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine 2022.” Retrieved from nobelprize.org.

Pääbo, S. et al. (2010). “A Draft Sequence of the Neandertal Genome.” Science. Retrieved from science.org.

Perrault, A. A. et al. (2019). “Rocking Promotes Sleep in Humans.” Current Biology. Retrieved from cell.com.

Reich, D. et al. (2011). “Denisova Admixture and the First Modern Human Dispersals into Southeast Asia and Oceania.” American Journal of Human Genetics. Retrieved from cell.com.

St-Onge, M. P. et al. (2016). “Fish Consumption and Sleep Quality.” Journal of Clinical Sleep Medicine. Retrieved from jcsm.aasm.org.