Tracing Ancient Shorelines: Field Notes from Java on Early Human Evolution

In mid-February, I returned to Southeast Asia—this time to Indonesia—together with Professor Erika Schagatay. At the start of our trip, we met up with Professor José Joordens, a Dutch anthropologist and paleoanthropologist. With her, we visited several excavation sites where she has been working, as well as museums in central Java.

José Joordens became widely known for her work on the engraved freshwater Pseudodon shell from Trinil—a remarkable artifact originally collected by Eugène Dubois and his team in the 1890s and later kept in Dutch museums.

The zig-zag engraving on one of these shells went unnoticed for more than a century. It was in fact archaeologist Stephen Munro who recognized the engraving already in 2007, while examining photographs he had taken of the shell collection in Naturalis Biodiversity Center. The finding was later formally described in 2014. The carving has been dated to between approximately 430,000 and 540,000 years ago, making it the oldest known example of an abstract or symbolic marking created by any human.

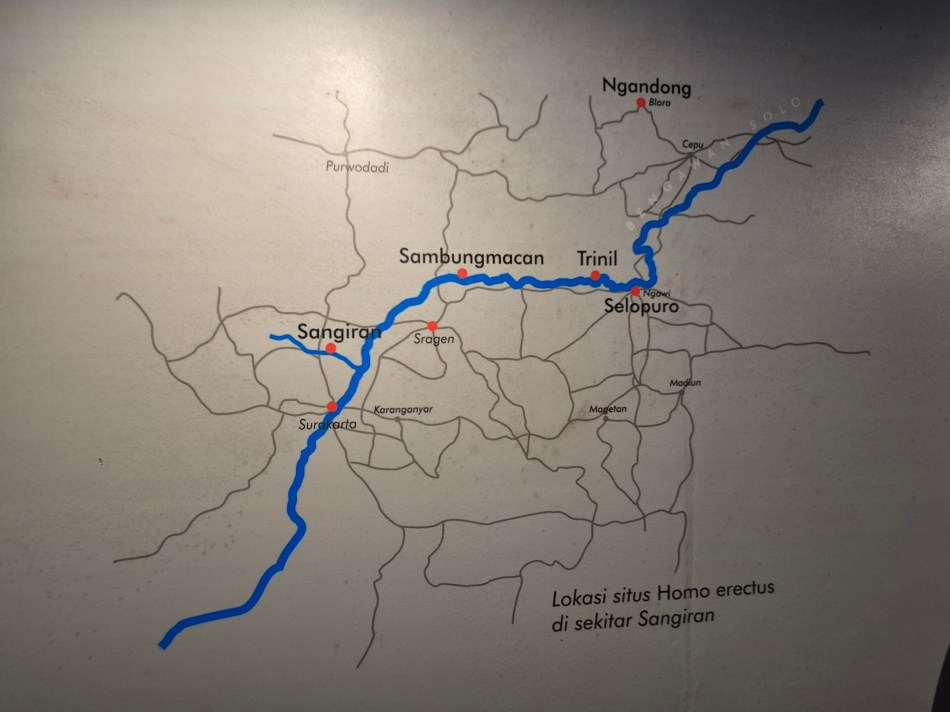

Along the Solo River and the World of Homo erectus

The Solo River basin is one of the richest regions in the world for Homo erectus discoveries. Groups of H. erectus lived along this river system from roughly 2 million years ago until as recently as 100,000 years ago, including the well-known Ngandong population—among the latest surviving Homo erectus known.

During our trip, Erika and José also met with numerous local researchers as part of early planning for a future interdisciplinary project on the Bajau Laut (Sama-Bajau) communities. The project aims to explore diving adaptations from physiological, anthropological, and cultural perspectives.

José has a long-standing interest in the waterside hypothesis and suggests that Homo erectus may have been shallow-water divers and foragers. The argument is supported by evidence such as thick cortical bones, a relatively dense skeleton, potential breath-hold capacity, and repeated associations with shell-bearing or riverine sites. The Trinil shell assemblage is central here, and it has also shown that shells were used as tools. In addition, José has excavated in Kenya’s Turkana Basin—another key region for early hominin interactions with aquatic environments.

Visiting Trinil: Dubois’s Historic Site

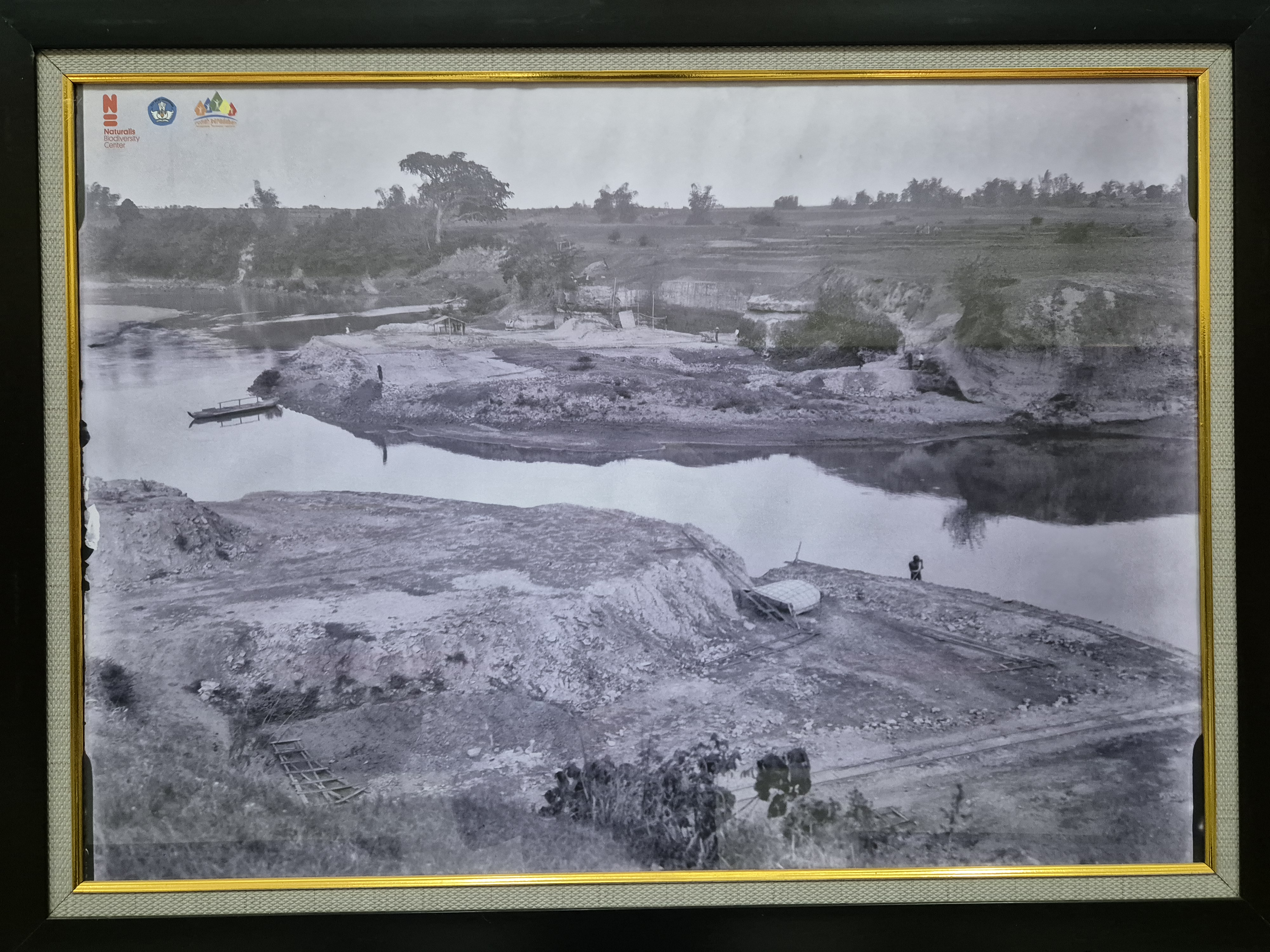

One of the highlights of our journey was visiting Trinil, where Eugène Dubois uncovered the first Homo erectus fossils—his famous “Java Man.” It was also here that the engraved shell was found. Local people still consider the site haunted, and many avoid being there at night. During Dubois’s excavations, prisoners were used as laborers, and a number of them died during the work, reportedly chained together and forced to excavate under horrific conditions.

We met long-time collaborators of José who have worked at Trinil for years. We also had access to a back room where numerous remnants, casts, and planning materials are kept, including a copy of the engraved Pseudodon shell. In the surrounding area, we also explored exhibitions and museums that highlight the life and environment of Homo erectus. Standing by the Solo River—where the earliest discoveries of Java Man were made, alongside men fishing with large handheld nets—brought a quiet sense of continuity between past and present.

A Waterside Landscape Two Million Years Ago

Java was a very different place two million years ago. The region was shaped by extensive river systems, lakes, wetlands, and coastal environments, and supported a wide range of mammals adapted to aquatic or semi-aquatic niches—such as hippos, elephants, and other water-associated species. Humans were part of this landscape, and this is also the region where Homo erectus appears to have persisted the longest.

Fossils attributed to Homo erectus appear in Africa at around two million years ago, including recent finds from sites such as Drimolen in South Africa, while the well-known Dmanisi material in Georgia dates to around 1.8 million years ago. In Southeast Asia, the Java record begins around 1.8 million years ago and continues until approximately 100,000 years ago.

Over this immense timespan, H. erectus brains increased in size—a gradual but significant development that may reflect changing environments and a long-term reliance on nutrient-rich aquatic and waterside resources.

In other parts of the world, Homo erectus either evolved into other lineages (for example through Homo heidelbergensis, often discussed as a common ancestor of Homo sapiens, Neanderthals, and Denisovans) or went extinct. Yet on isolated islands in Southeast Asia—such as Flores, Luzon, and Sulawesi—human species appear to have persisted much longer.

Water, Diving, and Human Evolution

Homo erectus had characteristically thick bones and may have been skilled divers. According to some researchers—especially Marc Verhaegen—the species’ history of breath-hold diving shaped both biology and behavior. Verhaegen argues that:

- Homo erectus frequently exploited coastal, riverine, and lake environments.

- Breath-hold diving may have been used to collect shellfish, aquatic plants, and other high-value foods.

- Their relatively heavy and dense skeleton may have functioned as natural ballast during shallow diving.

- In addition to diving, Homo erectus may often have floated on the back while foraging at the surface—somewhat comparable to modern sea otters—allowing extended time in the water with minimal energy expenditure.

- Long-term reliance on aquatic resources could have influenced brain growth and broader physiology.

- Cranial features such as paranasal air sinuses have been discussed in relation to pressure regulation and repeated submersion, though interpretations remain debated.

- Other traits sometimes highlighted include the ability to suck shellfish from shells and hypersensitive fingertips, well suited for detecting hidden prey while foraging underwater.

Homo sapiens later continued to exploit marine foods, which is significant given our need for DHA fatty acids to support a large brain. Although our species eventually became less dependent on diving, technological development likely allowed us to harvest aquatic resources in new and more efficient ways. Coastal foraging probably remained crucial even as our bodies became lighter and more specialized for long-distance walking and endurance running.

Average brain size in the human lineage increased steadily until roughly 300,000–200,000 years ago, after which it appears to have plateaued. A gradual reduction in average brain size becomes visible later, beginning around 50,000 years ago and continuing into more recent prehistory.

Given the high energetic demands of large brains, it seems likely that nutrient-rich foods centered on marine and aquatic resources played an important role during the period of brain expansion. The later reduction in brain size may reflect a gradual decrease in reliance on these resources as humans increasingly diversified their diets and food sources. Many large-brained mammals are closely tied to aquatic food chains during their evolution, which helps explain why the relationship between water, diet, and brain evolution remains such an intriguing topic.

Interestingly, some of the museums we visited—such as the Sangiran Museum Site—explicitly embraced the idea that Homo erectus lived close to water and may represent the earliest island-adapted human. Seeing this interpretation presented so openly was refreshing.

Engraved Shells and Shared Human Cognition

The Trinil shell itself is fascinating. Its zig-zag pattern resembles markings found in other early human contexts, such as the cross-hatched engravings made by early Homo sapiens on pieces of red ochre at Blombos Cave in South Africa (dated to about 73,000 years ago), as well as early Neanderthal engravings, including the cross-hatched markings from Gorham’s Cave in Gibraltar (~39,000 years old).

These similarities raise intriguing possibilities about shared cognitive tendencies—suggesting that geometric pattern-making may reflect deep underlying structures of human and pre-human thought. It also points to a long period when abstract marks existed without figurative art, before a later shift within Homo sapiens—after our species had already been around for more than 200,000 years.

Final Reflections

Traveling with José was inspiring. She is one of the few paleoanthropologists who treats the waterside hypothesis with genuine scientific curiosity, and her background as a marine biologist adds depth to her perspectives.

It is also striking that the earliest known sign of abstract behavior—an intentional engraving—comes not from stone tools or cave walls, but from a freshwater shell, further highlighting the importance of waterside environments in our evolutionary history.

The Cyclical Development: Ice Ages and “Great Leaps” Have Shaped Man

I have previously proposed a Copernican revolution in our understanding of human evolution. In this new article, I outline a broader developmental scheme for humanity, suggesting that we have undergone several great leaps, not just the one occurring 40,000 years ago. Historically, human development has not been about increasing creativity but about enhancing our ability to imitate and replicate behaviors established by our ancestors. Homo sapiens was thus originally a bodily materialization of an old way of life—an old survival strategy—that had been acquired by their predecessor, Homo heidelbergensis.

All standard models in human evolution have been extremely conservative. In their original form, all human species, including our own, have been deeply tradition-bound and produced standardized tools. It was the same Homo erectus who, at the beginning of their existence, manufactured Oldowan tools, later developed the Acheulean culture, and learned to make fire. The same Homo heidelbergensis who, 600,000 years ago, created standardized hand axes and, 400,000 years ago, developed the Levallois technique. The same Neanderthals who, 400,000 years ago, used tools similar to their predecessors, and around 160,000 years ago developed the Mousterian culture, began burying their dead, and created cave paintings. Likewise, Homo sapiens, who 300,000 years ago manufactured standardized Middle Stone Age tools, began 40,000 years ago to create microlithic tools, make sculptures, and spread across the globe.

Our evolution has followed a cyclical pattern, with climate changes like ice ages prompting periods of cultural innovation and biological adaptation. Each time we faced drastic environmental shifts, our latent creative abilities were awakened to develop new survival strategies. Language, which was originally a tool for imitation, became free in this process and created opportunities for symbolic thinking and social organization.

The advent of agriculture drastically changed the scene, as we gained the ability to fundamentally alter our environment. This development sheds new light on our situation today. With the power to reshape nature, there seem to be no limits; we strive to break all boundaries and even aspire to live forever—a sentiment most prevalent in technological hubs like Silicon Valley. In our pursuit to transcend natural constraints, we have become dangerously lost.

You can find the article here: The Cyclical Development: Ice Ages and “Great Leaps” Have Shaped Man

The Paradigm Shaping Our Understanding of Human Evolution

Our understanding of human evolution is not just a scientific endeavor but also a reflection of our self-perception and cultural preconceptions. These elements form part of the underlying paradigm—as discussed by Thomas Kuhn (1962)—or “doxa,” a concept similar to a paradigm introduced by philosopher Pierre Bourdieu (1977), that shapes our understanding of ourselves.

In this context, the theory of evolution, while groundbreaking, has not fundamentally altered our societal structures or self-conception. Instead, it has been adapted to reinforce the cultural and intellectual frameworks that have influenced Western thought for over two millennia, starting from the birth of philosophy.

In our modern, fast-paced culture, we have lost touch with the concept of stability in nature and society. We struggle to imagine a world where multiple generations coexist within the same deep-rooted reality. Our ancestors did not need to be perpetually inventive; rather, their lifestyles were remarkably stable—a fact evidenced by traditional hunter-gatherer societies like the !Kung people (Lee, 1979) and Australian Aboriginals (Tonkinson, 1978). The worldview of these traditional peoples was cyclical rather than linear (Eliade, 1954). In many traditional cultures, humans were regarded as immature and subordinate beings—apprentices to nature, the ultimate teacher (Ingold, 2000). However, over time, this worldview has shifted from being cyclical and holistic to linear, obsessed with the idea of progress and liberation from our natural limitations (Nisbet, 1980).

In previous blog posts, I have discussed the prevailing paradigm in anthropology that emphasizes human intelligence and flexibility, which can make it challenging to consider alternative theories like the aquatic ape theory. In this blog post, we will take a closer look at the deeper perceptions behind the current paradigm of flexible man.

Characteristics of Our Current Paradigm

Our current paradigm is closely intertwined with our views on economic growth and the valorization of entrepreneurship. We project our beliefs about ourselves onto our understanding of evolution, turning it into a form of storytelling. This narrative began with “Man the Hunter” (Lee & DeVore, 1968) and evolved into the “Savannah Hypothesis,” which, after being challenged, transformed into the concept of a mosaic of environments requiring constant flexibility (Potts, 1998). Human intelligence is seen as a trait akin to a lion’s strength or a cheetah’s speed. While animals became faster, more agile, and stronger, humans became smarter. Philosopher Karl Popper summarized this perspective well with his quote: “Our theories die in our place” (Popper, 1963, p. 216).

This paradigm is characterized by deep-seated feelings and assumptions, fundamentally unchanged over centuries—as elaborated by Thomas Kuhn in his concept of paradigms (Kuhn, 1962) and referred to as “doxa” by Bourdieu (1977). This enduring paradigm is not only evident in academic theories but also permeates our literature and cultural narratives. In literature, this perspective is vividly illustrated in Robinson Crusoe (Defoe, 1719), widely regarded as the first modern novel. Stranded alone on a remote island, Crusoe methodically tackles each challenge with resilience and ingenuity, viewing nature as a resource to be mastered. His journey reflects the Enlightenment-era view of man in his authentic state—capable of adapting, solving problems, and exercising rationality to shape his environment (McInelly, 2003). When he meets Friday, Crusoe regards him as a noble savage whom he begins to teach civilized behavior. Eventually, Friday refers to Crusoe as “Master.”

In anthropology, one of the central questions has often been why humans began walking on two legs. This shift to bipedalism was seen as a pivotal development that freed our hands for tool use and allowed for greater flexibility in our behavior (Darwin, 1871). Consequently, much of human evolution has been attributed to our own ingenuity and adaptability, enabling us to become masters of diverse environments.

However, transitioning from quadrupedalism to bipedalism required significant anatomical transformations, particularly in the structure of the knee and pelvis (Lovejoy, 1988). This raises questions about whether the intermediate stages could have been evolutionarily advantageous. Anthropologist Owen Lovejoy suggested that bipedalism arose to enable males to carry food to females, thereby promoting monogamy (Lovejoy, 1981). Such theories reflect our tendency to view human evolution through the lens of our own cultural values. The idea that males would carry food to a single childbearing female reinforces the ideal of monogamy, projecting contemporary social norms onto our ancestors—even though monogamy is not universal among human societies and is not genetically predetermined.

The Influence of Western Philosophy

The roots of our current paradigm can be traced back to ancient Greece. Thinkers such as Plato and Aristotle laid the foundation for the Western emphasis on reason and intellect. Aristotle’s idea of the “rational animal” positioned humans as unique in their capacity for logical thought (Aristotle, trans. 2000).

René Descartes, with his declaration “Cogito, ergo sum” (“I think, therefore I am”) (Descartes, 1641/1996), reinforced the centrality of human reason. Both Descartes and Aristotle were entrenched in the same paradigm that prioritizes rationality as the core of human identity. There has been a consistent thread in the history of philosophy, placing human intellect at the center and viewing it as the essence of humanity. Another manifestation of this enduring paradigm is seen in modern economics, where the “rational actor” model presumes individuals make decisions purely based on logical self-interest, reinforcing the ideal of human rationality.

The aquatic ape theory challenges this paradigm because it explains many human characteristics that anthropologists have traditionally thought did not require explanation. The theory forces us to recognize that, for most of our evolution, we lived in a semi-aquatic environment and were not the flexible entrepreneurs roaming the African terrestrial lands.

Back to the Roots of Evolutionary Theory

Let’s return to the basics of evolutionary theory. Evolution occurs through natural selection when a particular trait is not just successful in one or two generations but remains advantageous over many generations (Darwin, 1859). For evolution to occur, the same traits must be selected repeatedly, which means there must be continuity in development. Simplistically, evolution moves toward an adaptive peak—an optimal state. In evolutionary biology, the concept of an Evolutionarily Stable Strategy (ESS) suggests that there is a way of life, a particular strategy, that outperforms all others in a stable environment (Maynard Smith, 1982).

From this, we can conclude that as long as evolution is occurring, a species must live in the same way for generation after generation. When significant changes happen rapidly, evolutionary development can stagnate because there isn’t sufficient time for advantageous traits to be consistently selected (Gould & Eldredge, 1977). For example, the transition from Homo heidelbergensis to Homo sapiens involved not only an increased brain volume but also a lighter and more agile body structure, smaller jaws and chewing muscles, less robust bones, and more (Rightmire 2008), which is a clear indication that during this time, humans repeated the same living patterns generation after generation.

Human intelligence could not, as Alfred Russel Wallace argued, have arisen solely through traditional evolutionary processes focused on immediate survival advantages (Wallace, 1870). A highly specialized body and a flexible and creative brain do not typically emerge simultaneously under standard evolutionary models; these phenomena seem to exclude each other. The emergence of constantly activated creativity would require a prolonged period of environmental instability—a “continuity of chaos”—but nature rarely presents such conditions over extended timescales. Since our physical form has also undergone significant changes, human intelligence and language must have had original functions beyond mere survival adaptability. During evolution, we were, whether we like it or not, more animal-like.

Challenging the Paradigm

In essence, our understanding of human evolution remains a projection of our cultural self-image, shaped by enduring paradigms that elevate human reason and ingenuity. While a few philosophers like Martin Heidegger and Ludwig Wittgenstein have attempted to push humanity off its self-appointed pedestal, their insights have yet to permeate mainstream thought. Heidegger contended that Western philosophy over the past 2,500 years has gone astray, forgetting the fundamental question of being (Heidegger, 1927/1962). Wittgenstein argued that philosophical problems arise because we become entangled in our own rational language and that we must return to language in its everyday, original form to free ourselves from these confusions (Wittgenstein, 1953).

The new theory of human evolution that I have proposed is based on the idea that evolution has led to increased stability and the reproduction of behavior, making us more animal-like—with creative ability emerging latently as the other side of the coin. This theory correctly aligns with the principles of evolution and goes hand in hand with a more grounded, less anthropocentric view of our place in the natural world.

While physics has profoundly transformed our understanding of the universe—forcing us to accept theories that defy everyday intuition, such as relativity and quantum mechanics, which bear similarities to Zen Buddhism (Capra, 1975)—anthropology has not faced a similar upheaval. The theory of evolution, though it shook religious institutions, did not dramatically alter the narrative. It simply replaced divine creation with natural selection, maintaining the notion of human exceptionalism and behavioral flexibility. The time has come for us to question our long-held assumptions and embrace a paradigm shift that truly reflects the complexities of our evolutionary history.

References

Aristotle. (2000). Nicomachean Ethics (R. Crisp, Trans.). Cambridge University Press. (Original work published ca. 350 B.C.E.)

Bourdieu, P. (1977). Outline of a Theory of Practice (R. Nice, Trans.). Cambridge University Press.

Capra, F. (1975). The Tao of Physics. Shambhala Publications.

Darwin, C. (1859). On the Origin of Species. John Murray.

Darwin, C. (1871). The Descent of Man, and Selection in Relation to Sex. John Murray.

Defoe, D. (1719). Robinson Crusoe. W. Taylor.

Descartes, R. (1996). Meditations on First Philosophy (J. Cottingham, Trans.). Cambridge University Press. (Original work published 1641)

Eliade, M. (1954). The Myth of the Eternal Return: Cosmos and History. Princeton University Press.

Gould, S. J., & Eldredge, N. (1977). Punctuated equilibria: The tempo and mode of evolution reconsidered. Paleobiology, 3(2), 115–151.

Heidegger, M. (1962). Being and Time (J. Macquarrie & E. Robinson, Trans.). Harper & Row. (Original work published 1927)

Ingold, T. (2000). The Perception of the Environment: Essays on Livelihood, Dwelling and Skill. Routledge.

Kuhn, T. S. (1962). The Structure of Scientific Revolutions. University of Chicago Press.

Lee, R. B. (1979). The !Kung San: Men, Women, and Work in a Foraging Society. Cambridge University Press.

Lee, R. B., & DeVore, I. (Eds.). (1968). Man the Hunter. Aldine Publishing.

Lovejoy, C. O. (1981). The origin of man. Science, 211(4480), 341–350.

Lovejoy, C. O. (1988). Evolution of human walking. Scientific American, 259(5), 118–125.

Maynard Smith, J. (1982). Evolution and the Theory of Games. Cambridge University Press.

McInelly, B. C. (2003). Expanding empires, expanding selves: Colonialism, the novel, and Robinson Crusoe. Studies in the Novel, 35(1), 1–21.

Nisbet, R. A. (1980). History of the Idea of Progress. Basic Books.

Popper, K. R. (1963). Conjectures and Refutations: The Growth of Scientific Knowledge. Routledge.

Potts, R. (1998). Variability selection in hominid evolution. Evolutionary Anthropology, 7(3), 81–96.

Rightmire, G. P. (2008). Homo heidelbergensis and Middle Pleistocene hominid evolution in Europe and Africa. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 105(48), 19065–19070.

Tonkinson, R. (1978). The Mardu Aborigines: Living the Dream in Australia’s Desert. Holt, Rinehart and Winston.

Wallace, A. R. (1870). Contributions to the Theory of Natural Selection. Macmillan.

Wittgenstein, L. (1953). Philosophical Investigations (G. E. M. Anscombe, Trans.). Blackwell.

Hard Evidence of Early Human Seafaring and Women’s Role in Marine Foraging

New and fascinating discoveries provide hard evidence for the Aquatic Ape theory, evidence that was not known when Alister Hardy and Elaine Morgan first advocated for this idea. There is now substantial data proving that early humans undertook long maritime journeys, developed unique physiological adaptations, and lived lives closely tied to water. In this blog post, I will examine some of the compelling evidence that supports a semi-aquatic past for humans. These pieces of evidence meet the stringent criteria set by the anthropological community, which demands archaeological proofs for our evolutionary history, rather than merely examining our own bodily adaptations.

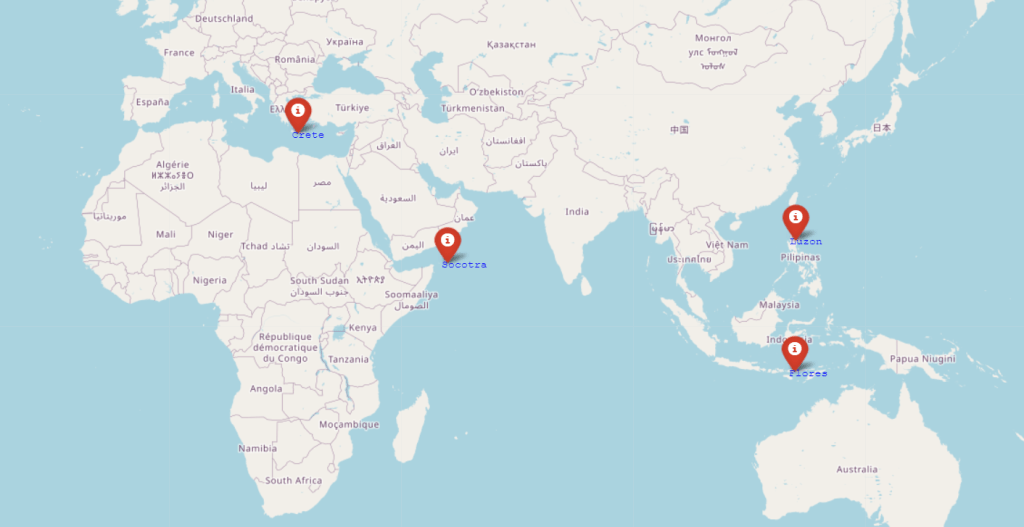

Long Early Maritime Journeys

Early human species undertook impressive sea voyages, as evidenced by discoveries of human fossils and stone tools on distant islands that have been separated from the mainland for millions of years. For instance, Homo sapiens reached Australia about 65,000 years ago, a journey that required crossing at least 70-100 km of open sea from Indonesia, traversing the significant biogeographical barrier known as Wallace Line (O’Connell, Allen, & Hawkes, 2010). Similarly, Homo heidelbergensis or Neanderthals reached Crete around 130,000 years ago, leaving hand axes behind and crossing water distances of approximately 40 km (Strasser et al., 2010).

Even more spectacular are the colonization events of Luzon in the Philippines, Socotra in the Indian Ocean, and Flores in Indonesia. The colonization of Luzon, evident from the discovery of Homo luzonensis dating back 67,000 years, required crossing the Huxley Line, another notable biogeographical barrier, involving a journey of at least 250 km from the nearest landmasses (Detroit et al., 2019). Evidence also suggests that Oldowan toolmakers reached Socotra several hundred thousand years ago, which would have required a sea journey of approximately 80 km from the African coast (Amirkhanov et al., 2009). Additionally, the colonization of Flores, marked by the discovery of Homo floresiensis, also known as the Hobbit, required a journey of around 30-40 km of open sea (Morwood, Oosterzee, & Sutikna, 2007).

It is likely that Socotra, Flores, and Luzon were places where more archaic human species could live relatively undisturbed for long periods. For instance, the discovery of Oldowan tools on Socotra, which first appeared around 2.6 million years ago and were made by the ancestors of Homo erectus, suggests a very ancient colonization of the island (Semaw, 2000; Amirkhanov et al., 2009). The first settlers on Flores and Luzon were also likely from species predating Homo erectus, based on analyses of the fossils of Homo floresiensis and Homo luzonensis, which exhibit some archaic features (Morwood, Oosterzee, & Sutikna, 2007; Detroit et al., 2019). Given that these are all very isolated islands, it is entirely possible that early hominids lived throughout much of Southeast Asia for extended periods but were eventually pushed out when Homo erectus settled in the region, surviving late only on islands far out at sea.

All this evidence indicates that humans have been well-acquainted with aquatic environments for a couple of million years and suggests that humans probably lived scattered throughout the maritime world of the Eurasian coastline. This is also a clear sign that they could build floating structures or boats to undertake these maritime journeys.

Clues from Kalambo Falls

One clue to how these early floating structures might have been constructed can be found at Kalambo Falls in Zambia. Archaeologists have discovered the oldest known wooden structures here, dated to around 476,000 years ago. These structures consist of two interlocking logs joined by an intentionally cut notch. The researchers behind this finding believe the structures were likely used as a stable platform in a wet environment, which may have included use as a raft or dock (Barham et al., 2023).

The preservation of these wooden structures was possible because they became waterlogged, meaning they were submerged in water and saturated, preventing decomposition by creating an anaerobic (oxygen-free) environment (Barham et al., 2023). This remarkable preservation provides further evidence of early humans’ ability to use wood to create structures for aquatic activities.

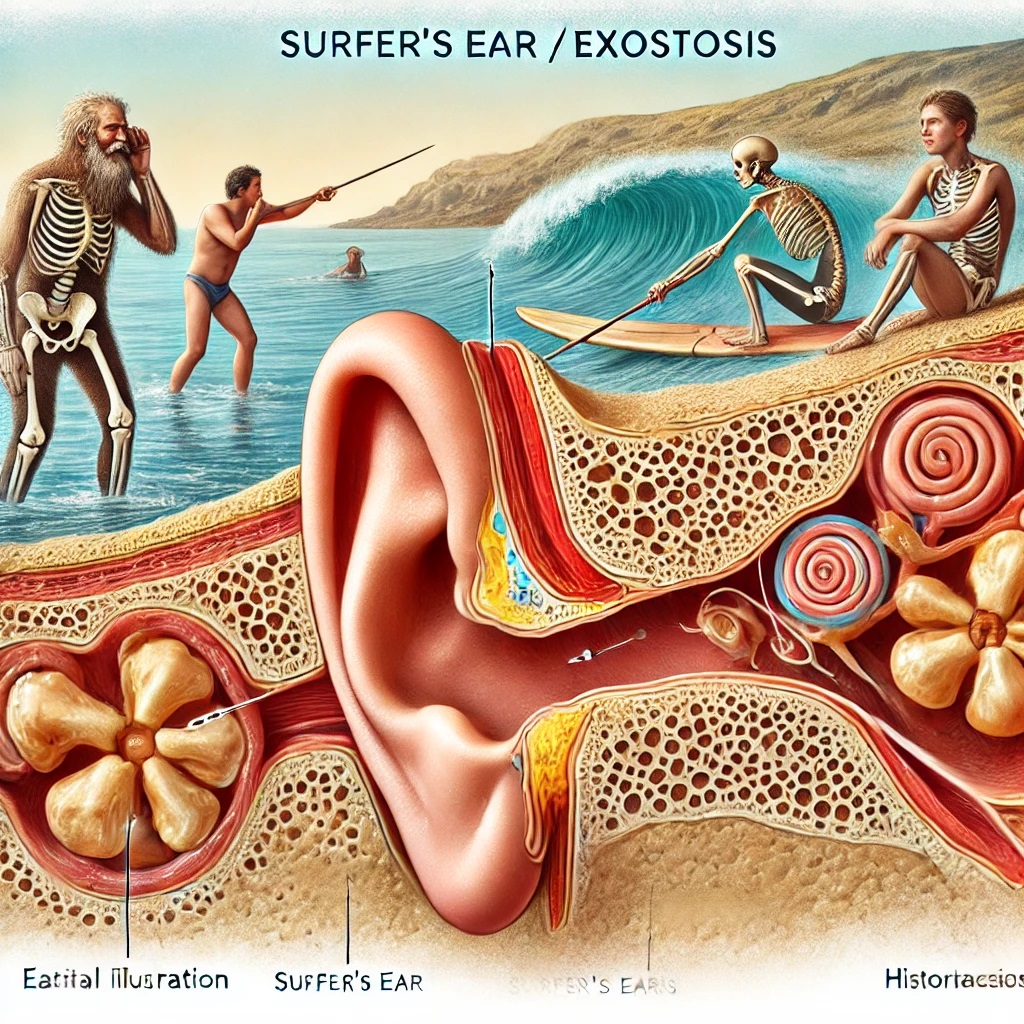

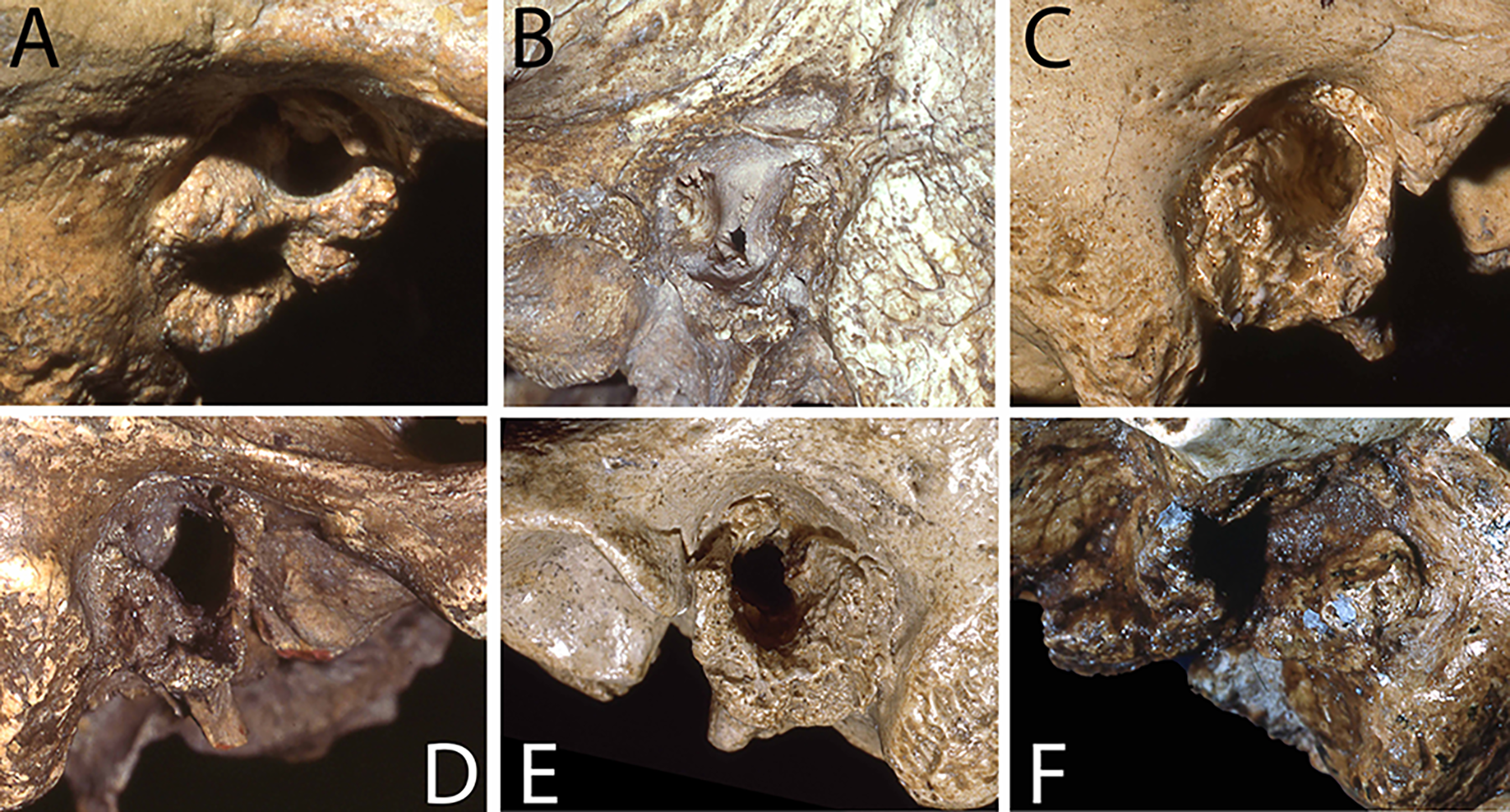

Surfer’s Ear: Evidence of Aquatic Adaptations in Early Humans

Surfer’s ear, or exostosis, is a bony growth in the ear canal that develops from prolonged exposure to cold water. Research by Trinkaus, Samsel, and Villotte (2019) has shown that a significant percentage of both Neanderthal and early Homo sapiens fossils in Eurasia exhibit this condition. In a study examining 77 fossils with well-preserved ear canals, it was found that these early humans were frequently in cold water environments, likely for marine foraging activities (Trinkaus, Samsel, & Villotte, 2019).

In the study, 48% of the Neanderthal specimens investigated had Surfer’s ear. While it was often difficult to determine their sex, among the identified Neanderthal women, three out of four had this condition (Trinkaus, Samsel, & Villotte, 2019). Similarly, Surfer’s ear was prevalent in Homo sapiens fossils, with approximately 25% of Middle Paleolithic specimens (300,000 to 30,000 years ago) showing the condition. The prevalence was 20.8% during the Early/Mid Upper Paleolithic (50,000 to 30,000 years ago) and dropped to 9.5% in the Late Upper Paleolithic (30,000 to 10,000 years ago), indicating a change in lifestyle (Trinkaus, Samsel, & Villotte, 2019).

Interestingly, in the 19 sexable Early/Mid Upper Paleolithic Homo sapiens specimens, Surfer’s ear was present in 16.7% of males and 28.6% of females. This suggests that more women than men exhibited this condition in early Homo sapiens (Trinkaus, Samsel, & Villotte, 2019). These findings support the hypothesis that women, due to their thicker layer of subcutaneous fat, were better suited to spending extended periods in water and were likely more involved in diving activities. This evidence highlights the significant role aquatic environments played in the lives of early humans.

Moreover, findings from Panama show that even people living in warm environments can develop Surfer’s ear when they engage in deep diving where the water is colder. This observation is supported by the analysis of fossils dating back thousands of years (Arias-Martínez et al., 2019), further emphasizing the connection between human activity and aquatic environments across different climates and time periods.

Conclusion

These pieces of evidence collectively paint a compelling picture of how early humans thrived in and around water. From navigating long distances over open seas to developing physiological adaptations to cold water environments, much also indicates that women were perhaps more involved than men in diving activities during this time.

As we uncover more about our past, it becomes clear that our relationship with water has profoundly shaped our evolution. These findings not only challenge previous notions about early human behavior but also open new avenues for understanding the complexities of our development. The future of exploring our aquatic heritage lies in continued research and the growing field of underwater archaeology, promising even more fascinating discoveries.

Literature

Amirkhanov, K. A., Zhukov, V. A., Naumkin, V. V., & Sedov, A. V. (2009). Эпоха олдована открыта на острове Сокотра. Pripoda, 7.

Arias-Martínez, L., González-Reimers, E., Velasco-Vázquez, J., Santolaria-Fernández, F., & Hernández-Moreno, M. (2019). Auditory exostoses and their relationship to environmental factors in the pre-Hispanic Canary Islands. American Journal of Physical Anthropology. https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/abs/10.1002/ajpa.23757.

Barham, L., et al. (2023). Earliest Evidence of Structural Use of Wood at Kalambo Falls. Nature. https://www.nature.com/articles/s41586-023-06557-9.

Detroit, F., Mijares, A. S., Piper, P., Grün, R., Bellwood, P., Aubert, M., … & Zeitoun, V. (2019). A new species of Homo from the Late Pleistocene of the Philippines. Nature, 568(7751), 181-186.

Morwood, M. J., Oosterzee, P. V., & Sutikna, T. (2007). The Discovery of the Hobbit: The Scientific Breakthrough that Changed the Face of Human History. Random House.

O’Connell, J. F., Allen, J., & Hawkes, K. (2010). Pleistocene Sahul and the Origins of Seafaring. Cambridge Archaeological Journal, 20(1), 69-84. doi:10.1017/S0959774310000055.

Strasser, T. F., Panagopoulou, E., Runnels, C. N., Murray, P. M., Thompson, N., Karkanas, P., … & Coleman, J. (2010). Stone Age seafaring in the Mediterranean: evidence from the Plakias region for Lower Palaeolithic and Mesolithic habitation of Crete. Hesperia: The Journal of the American School of Classical Studies at Athens, 79(2), 145-190.

Trinkaus, E., Samsel, M., & Villotte, S. (2019). External auditory exostoses (Surfer’s ear) in the human fossil record: A proxy for behavioral adaptations to aquatic resources. PLOS ONE, 14(8): e0220464. https://journals.plos.org/plosone/article?id=10.1371/journal.pone.0220464.

The Rise of Modern Behavior: A Copernican Revolution in Understanding Human Evolution

Have we misunderstood the true essence of human evolution and the role of language in our ancient past? In a new article, I propose a Copernican shift in our understanding of language’s original function and the cognitive revolution that began approximately 75,000 years ago.

Traditional views hold that language evolved primarily as a tool for enhanced communication and complex thought. However, this article suggests that language’s original role was more about replicating behaviors linked with tool use, transferring these behaviors from one generation to the next through singing and rhythm. Initially, language served to reconcile the gap between the human body and its environment, which arose with the advent of the first stone tools, enabling early humans to navigate landscapes for which they were not biologically adapted.

This theory resolves a longstanding paradox since the inception of evolutionary theory: although thinking has an evolutionary past, and Homo sapiens are estimated to be 300,000 years old, humans have not always been ‘modern.’ What if humans are not inherently meant to think and act as they do today? What if evolution promoted aspects other than intellectual capability? Accepting this paradox might mean acknowledging that humans have undergone both a gradual evolutionary process, as Darwin suggested, and a rapid developmental leap, as indicated by archaeological findings—without any genetic change in the brain.

This new theory draws support from a diverse array of disciplines. Archaeological records reveal sporadic bursts of creativity alongside a gradual brain development; meanwhile, studies on mirror neurons offer a neurological basis for mimicry and observational learning, essential for transmitting skills and behaviors across generations. Additionally, theories about our aquatic past propose that water-based environments laid the groundwork for the evolution of vocalization and singing. Insights into how children acquire language—focusing on the roles of intonation and rhythm—mirror the significant role that song played over speech. These interdisciplinary findings suggest that our evolutionary path was not a straightforward march towards greater intellectual capability but rather a complex journey marked by periods of significant conformity punctuated by bursts of creative potential since the first stone tools 2.6 million years ago. This perspective helps explain not only the creative outbursts in South Africa 75,000 years ago but also other instances of early possible symbolic behavior, such as the use of shell beads by early Homo sapiens and Neanderthals.

Moreover, this perspective aligns with various global mythologies that narrate an ancient, harmonious coexistence with nature, disrupted by the cognitive revolution. Could the hauntingly beautiful cave paintings, some of the earliest known forms of human art, be interpreted not just as artistic expressions but as calls for help? These artworks could be seen as profound expressions of a deep-seated longing for reconnection with the natural world we once knew.

You can find the article here: The Rise of Modern Behavior: A Copernican Revolution in Understanding Human Evolution

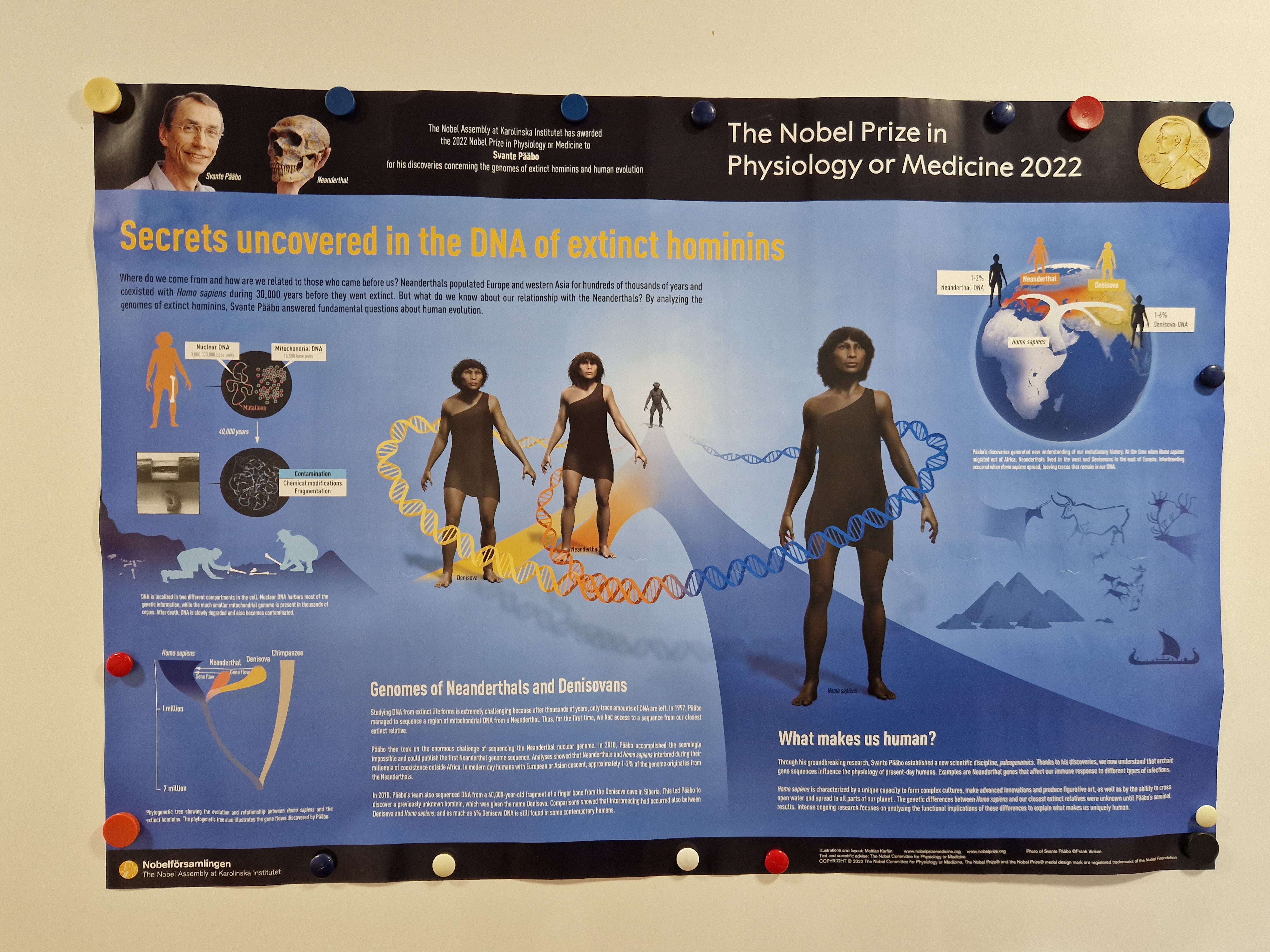

Exploring Human Evolution: Visit at The Max Planck Institute in Leipzig

From May 22nd to May 24th, I had the opportunity to travel to Leipzig, Germany, where I visited the Max Planck Institute for Evolutionary Anthropology and met with PhD student Jae Rodriguez. This visit was both educational and inspiring, offering insights into the world of evolutionary anthropology and the fascinating research being conducted at this renowned institution. Only six months before my visit, Svante Pääbo, the director of the Department of Evolutionary Genetics at the institute, had been awarded the Nobel Prize in Medicine for his groundbreaking work on Neanderthal genomes (Nobel Prize, 2022).

During my stay, I gave a presentation on the Bajau Laut titled “Sama Bajau: Lifestyle, History, Evolution” to a group of students, postdocs and senior scientists as part of their “Ocean’s Meeting” series. In my presentation, I delved into their rich history, cultural significance, and the political factors influencing their way of life. Additionally, I explored the physiological aspects of their connection to the sea, such as their remarkable sense of well-being while living on the water. Scientific studies support this connection, showing that the rocking of waves improves sleep quality (Perrault et al., 2019), natural water sounds enhance relaxation (Gould van Praag, 2017), consuming marine food improves sleep quality (St-Onge, 2016), and more.

Jae Rodriguez, the PhD student who hosted me, focuses his research on the genetic origins and adaptations of the indigenous inhabitants of the Sulu Archipelago in the Philippines. A significant part of Jae’s research involves samples from over 2,000 Sama Bajau individuals in the southwestern Philippines, particularly around Tawi-Tawi, which are carefully stored in one of the institute’s labs. This material is crucial for mapping the Sama Bajau’s history and gaining a broader understanding of their genetic adaptations and unique lifestyle. It would be fascinating to delve deeper into the genetic sequences related to spleen size that Melissa Ilardo studied when she researched Bajau Laut divers in central Sulawesi, Indonesia. She found that the Bajau Laut in the area had undergone natural selection for larger spleens over at least a few thousand years (Ilardo et al., 2018).

I first met Jae Rodriguez at a conference in the Philippines in 2015, and we have kept in touch since then. It was a true pleasure to meet up with Jae in Leipzig and discuss the Bajau’s history, lifestyle, evolution, and future challenges, as well as other aspects of human evolution.

Jae also gave me a tour of the Max Planck Institute, including an exhibition on the ground floor about human history. I was looking forward to meeting Svante Pääbo, who also hails from Sweden, but despite his office being wide open, he was not around at the time. Outside his office, a Neanderthal skeleton was on display. Pääbo was the first scientist to sequence the entire genome of a Neanderthal, proving that Homo sapiens and Neanderthals had shared offspring, which has medical implications still today (Pääbo et al., 2010). A few years later, he also sequenced Denisovan DNA, revealing genetic traces in modern humans, particularly in Southeast Asian island populations, where up to 5% of some groups’ genes come from Denisovans (Reich et al., 2011). These discoveries have changed our understanding of the complexity of human evolution and made us realize how similar we are to our closest cousins who live on within us.

The institute itself is a dream destination for anyone interested in human evolution. It brings together scientists from diverse fields, including natural sciences and humanities, to investigate human history through interdisciplinary research. Their work includes comparative analyses of genes, cultures, cognitive abilities, languages, and social systems of both past and present human populations, as well as primates closely related to humans. The institute also hosts young doctoral students from around the world who delve into historical and genetic research from their own regions (Max Planck Institute for Evolutionary Anthropology).

My visit to the Max Planck Institute for Evolutionary Anthropology was a remarkable journey into the depths of human history and genetics. The opportunity to share my research on the Bajau Laut, explore cutting-edge scientific work, and connect with passionate scholars made this trip an unforgettable experience. As the field of genetics rapidly develops, new methods for analyzing ancient fossils will hopefully emerge. These new findings will reveal that even more populations have contributed to who we are today, making us even more humble about our origins and who we are.

References

Gould van Praag, C. D. et al. (2017). “The Influence of Natural Sounds on Attention and Mood.” Scientific Reports. Retrieved from nature.com.

Ilardo, M. A. et al. (2018). “Physiological and Genetic Adaptations to Diving in Sea Nomads.” Cell. Retrieved from cell.com.

Max Planck Institute for Evolutionary Anthropology. “About Us.” Retrieved from eva.mpg.de.

Max Planck Institute for Evolutionary Anthropology. “Prof. Dr. Svante Pääbo.” Retrieved from eva.mpg.de.

Nobel Prize. “The Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine 2022.” Retrieved from nobelprize.org.

Pääbo, S. et al. (2010). “A Draft Sequence of the Neandertal Genome.” Science. Retrieved from science.org.

Perrault, A. A. et al. (2019). “Rocking Promotes Sleep in Humans.” Current Biology. Retrieved from cell.com.

Reich, D. et al. (2011). “Denisova Admixture and the First Modern Human Dispersals into Southeast Asia and Oceania.” American Journal of Human Genetics. Retrieved from cell.com.

St-Onge, M. P. et al. (2016). “Fish Consumption and Sleep Quality.” Journal of Clinical Sleep Medicine. Retrieved from jcsm.aasm.org.